This album presents a perfect case study in wallpaper black metal and a discussion of its apologetics. The title, formed from three repetitions of the Swedish word for “holy,” incurs two different wallpaper metal infractions: pointless repetition of riffs and pointless contrasting ideas.

Pointless repetition of an entire rhythm or riff, as opposed to reusing a theme in a different context, occurs when a composer has one of several possible aims. Traditionally this has been to let the listener get familiar with an idea, to let it sink in, as some would say. The most popular aim of repetition in the more ambient-oriented black metal field is to create atmosphere. The aim of the latter is to lead the listener beyond familiarity with the riff and into a kind of stupor. The listener is taken into this state with the purpose of preparing him for something else: a deeper dream level, as it were, which would follow. But apologetics of wallpaper music claim that all ambient-oriented repetition, even the one they themselves may admit to being meaningless, achieves its goal if it brings the listener to the aforementioned state of stupor without necessary deepening of mood.

Pointless contrasting ideas serve to redirect of a musical path or modify the nature of the stupor in which the listener is in, such as from an anger-fueled one to another infused by sadness or even happiness. The use of a contrasting idea makes sense if it interacts with its context and primarily with its adjacent riff sections, much as in writing each sentence in a paragraph must relate to the topic and the sentences before and after it. When contrast lacks that purpose in context, it becomes a technique for distracting from the stupor so that the listener does not realize that the trick behind the stupor is repetition alone and it will lead nowhere, which converts a dream-state into a state of boredom in instants.

Wallpaper Music

Wallpaper is defined as: “paper that is pasted in vertical strips over the walls of a room to provide a decorative surface.” It provides a decorative surface only without reference to what surrounds it. Its context does not matter so long as it covers a blank surface and provides something to look at. It is not meant to have any meaning. The frescoes, carvings or statues of classical art, on the other hand, were meant to be both pleasing to the eye and to convey a certain meaning, inviting the visitor into a different dimension (in the mystic-spiritual metaphorical sense).

Now the following question assails us, would someone completely unfamiliar with Western art become induced into the mental state that the authors of such art intended? Not necessarily. The degree to which that person’s reaction to art approaches that which was intended depends directly on the similarity of the background in culture and experience of the subject to that whence the artwork sprung from. This, like context, comprises the memories that give a new musical figure meaning.

In fact, herein lies our key to reverse engineering intention (of the author) and/or purpose (which may be independent of the author’s conscious intent) in music. This key is context. Let us be clear here that this does not refer to Epistemic Contextualism, which does not lead to a discussion on inherent meaning arising from some original intention but to that of attributed meaning as interpreted in any situation, even alien contexts to that which gave rise to the original product. The intended meaning of context in this article is precisely the conventional one described in the previously linked article as:

…certain features of the putative subject of knowledge (his/her evidence, history, other beliefs, etc.) or his/her objective situation (what is true/false, which alternatives to what is believed are likely to obtain, etc.)…

This allows us to appreciate the sense and coherence of a work independently of if we agree with its tenets. On a separate but related note, it is also from this vantage point that its connection to a more transcendent nature can be gauged, since the particular context, that which is temporal, is known.

Analyses, use, limitations and power

Perceiving context in a particular way and analyzing a problem in the real world is the subject of studies that produce methods to approach them. Everything that is perceived is subjective in the sense that depending on our experience and background we may highlight and give importance to different factors. After that, methods are devised to point out objective qualities that are pertinent to the aspects we want to analyze. This is true of mathematical analysis, and even of scientific analyses in chemistry and physics.

Of course, there is a catch here. The complexity, in terms of scope, of what is being analyzed matters in no small measure to the objectivity of the results. In the case of the sciences, the scope is reduced to what is known while assumptions are made about what is not known and then, given the reduced and strictly defined boundaries of what is being analyzed (which is usually not the whole system but rather a model of the system), completely objective results are obtained in the context of the reduced-system model. As a more knowledgeable person in the field would put it:

The larger the scope of the analysis of a system becomes, the more assumptions regarding the conditions that enable the system to behave in a certain way become present. Sometimes these assumptions are made deliberately, but sometimes they are present unknowingly. This is due to the complexity associated with an increasing scope of analysis, which makes it unfeasible to obtain a straightforward solution. Furthermore, complexity is associated with the relationship among the different factors (variables) and the system/phenomena being observed. — L. Garrido

The error factor grows alongside this scope and it may even become unmeasurable if we do not know how to precisely quantify a particular element like purpose or intention. Which is precisely why they are not included in the scope of any scientific analysis. It must also be clarified that the error factor of a problem does not represent its concrete error, but the maximum magnitude of all possible errors. Meaning our analysis could indeed be perfect, although this is unlikely.

Analysis in Music

In music, a very wide scope must be admitted into its analysis. This is necessarily so since we acknowledge that music is much more than the notes themselves, than the organization of these notes alone, than the context in which they are perceived, or the intentions of the artist. Musical quality encompasses all of them at the same time and, in a Renascentist-Magical holistic view, ultimately engenders a separate entity altogether which is none of these elements and is rather born from all of them. Any music analysis consists on the breaking of music down to its components with the aim of understanding how they function as parts of a greater whole.

One of the most intriguing techniques for the analysis of “conventional” tonal Western music is called Schenkerian analysis. This was a system named after the theorist who devised it, Heinrich Schenker (1868-1935). It consists of demonstrating how music can be divided into a hierarchy of notes which range from background indispensable notes to more those of a more “auxiliary” nature, although the terms “neighboring” and “passing” are more suitable since they do not carry such a strong connotation of these notes being less part of the music. Before him came Arnold Bernhard Marx (1795-1866) whose revolutionary way of analysing music included judging the purpose, character and direction in music independently of the composer’s conscious awareness through the subdivision of sections until one finds indivisible components. These can belong to one of two kinds: the self-sufficient and assertive Satz or the motion-oriented, forward-moving Gang. Schenker’s method is, in a way, a formalization of the more intuitive process of Marx, who used a more holistic approach (and a wider scope, more assumptions), into a more mechanical approach — though still subjective to a certain degree.

Despite wild claims by detractors of this way of analyzing music which want to reduce Schenkerian analysis to subjective make-believe so as to dismiss any objective value in it, an argument is to be made in favor of its objective and logic and characteristics. The user of this analysis at his best can be compared to a detective following clues. The best detectives are not clueless idiots blindly following a manual. Detectives first take note of context, use psychology and decipher motives and even subconscious processes that the criminal himself might not be aware of. There is a lot of guessing involved, but educated guessing, which while being subjective interpretation cannot just be dismissed as simple opinion (in the passive-derogative and dismissive sense) since it follows a method based on objective points. It is important, of course, to point out that the detective also relies heavily on experience.

It is here that we turn again to the idea of context. The ideas of direction, stability and instability, and character inherent to these style of analyses is born out of concrete knowledge of the development of music during the Common Practice Period (roughly 1600s up to 1900). These are “concrete” in the sense that they were not just an archaeological approach to understanding the past, in which the theorist is separated from the data in question and is always forced to look at it from the outside. Rather, the theorists who developed these analyses were part of the musical “subculture” (and the culture at large which encases it and is an audience to it) which engendered the music they studied. So their subjective views and experience are, in my opinion, validated as relevant by that same fact that places them as insiders.

The reader might rightly question this last claim denouncing that this in itself cannot possibly give the theorists and historical critics license to judge the music at the subjective levels previously mentioned. I will address this by calling attention to the music theory “standard”, or rather a “musical language”, that came into being in the first half of the 17th century thus producing what we know now as the Common Practice Period. This language is based on harmony that is built by contrapuntal norms, avoids certain musical effects and favors a narrative style. From its very beginning up until the 19th century, a certain significance, as meaning in a spoken language, was attributed to musical phrases, melody direction and movement, harmonic tension or instability, together with rhythm. What is relevant about this is not that these beliefs existed, but that they were part of the music education and culture of that time. The rules and conventions (even the ones relating to extra-musical implications) by which these theorists and critics measured and judged music were the same that the composers themselves ascribed to. This does mean that some of the less talented critics would see superficial aspects as set in stone, but this was not true of A.B. Marx who saw music as an everflowing, ever-evolving transformation of styles whose steps beyond what he knew in his time were only as visible as vague shapes in the horizon.

Is the application of Western European analysis and philosophy to metal music really justified?

Now, if this analysis belongs to the Common Practice Period, would it be fair to apply it to metal music? After all, the processes that produced Metal music are different. It would not make sense to apply the same analysis to Iranian or Indian music which follow their own systems whose musical constructions have inextricable spiritual and religious significance in the culture that engendered it. Neither would we thus judge jazz, which is the result of African-American music borrowing European art music notions to produce a language and a more sensual purpose of its own. My opinion is that we can say jazz gets excused because the ultimate product is more African-American than European.

When taking a look at music and judging its “coherence” one can metaphorically refer to it as its logic. When taking a look at a logical argument, we first take look at the premises or assumptions and from there follow it through its process. If the argument fails to make sense based on its premises we can say it has failed. The same applies to music. We can judge musical construction according to the premises it sets for itself. The style it chooses, yes, but more importantly, the general music language (Iranian classical music has different harmonic notions and goals, for example, as does jazz) it chooses for itself.

Metal starts with Black Sabbath taking rock-based music (which itself subscribes to the use of Common Practice Period harmony, but used in a more mechanical way to produce simple verse-chorus music) and bringing back the more theme-based approach of horror movie soundtracks. Soundtracks which were themselves inspired on 19th-century Romantic music. From then on metal develops as this rock-and-dark-Romantic musical hybrid and at different points borrows elements from other music genres but always distinguishing itself as Metal by always keeping an entrenched Romantic music orientation. One can then distinguish deserters who fled to the rock camp by abandoning of this orientation (Metallica is a clear example). The more the genre evolved the more marked the difference between rock defectors and those who remained metal became. This is because the latter would try to distinguish themselves more from the rock element which was so prominent in the former. This is the process that originally gave rise to the terms sell-out and underground. It must be clarified that what is meant here is not that the rock element in any music is bound to produce poor music.

The only constant at the heart of metal then, is the Romantic sense of theme-based music with a serious and heavy character. From this point it follows that the “premises” that metal has chosen for itself stem directly from the Common Practice Period in general. This does not mean that we should try to read metal music as we would read a Beethoven symphony — at least not on the surface. The characteristics that metal has borrowed from classical music affected the genre at multiple levels and thus surfaces in different bands in different ways and to different degrees. We cannot judge all metal in the same way either because just as different musical genres choose different languages (different premises for their arguments), so it is that different bands choose dialects of their own which require us to understand them and part from there on. But they must be seen as precisely that: dialects of the broader language of metal. Thus they still fall under the umbrella of our discussion (Ildjarn would be a particularly interesting case to discuss as its surface and the first impression it gives one leaves no room for obvious comparison to Romantic traits).

One understands the intense repetition of some black metal as stemming from the same purpose it has in electronic music. Black metal remains metal because it still ascribes to the dark-Romantic principles metal is defined by. Part of this is tonality and how harmony is used to create movement, which along with rhythm creates pulse and is tied by theme and the large-scale interplay of sections. Part of it is the more complex interpretation of how the character of each section and song speaks out and relates to the other sections or songs.

This character was an important trait during the Common Practice Period and it plays an important role in metal. When it goes unchecked, even if the outer technical aspects of music were all carefully crafted, the inner sense is perceived to be empty or messy. This thinking was very evident in the thoughts of both great composers and historical critics from the Romantic period such as Philipp Spitta (1841-1894) whose biography of Johann Sebastian Bach reveals extensive discussion, analysis and critique that encompasses everything from historical context and evolution of genres along with their influence over the German master, to detailed score analysis and explicit separation of what he refers to as “inside” and “outside” musical traits. The latter being musical expression itself, the structures, and the former being the character/aura/personality of not only the music pieces themselves but also of individual sections and their relation to the whole.

Modern metal unknowingly fails catastrophically by trying to create interest out of pure contrast. Still, some of the best modern bands keep a constant style and even use theme to tie a song together, but little or no evident thought is put into the aura of each section of a song and its balance with the rest of the song (see Fallujah).

The modern variety of metal bands which identify as “technical” (as opposed to Atheist, Immolation or Gorguts which were dubbed so after the fact) try to create interest by approaching this as if it were a textbook exercise, playing with the theme, placing it in different contexts, creating smart texture changes and witty variations. Since all that was cared about was the technical correctness of the piece, the evocation power of the music is negligible as it is not born out of Idea, but out of technical exploration (see Ara). The apologist comes in at this point and says that “emotion” is also in the process and that all parts are judged by passing them through this emotional filter. This is never denied here. But this statement would actually reinforce the notion that this music follows a backwards process: outside to inside, rather than inside to outside. The writer of purely technical music uses hard logic to drive his music creation and then judges it from an emotional vantage point. This works for science, but it spells out death for art.

Whereas in all productive men instinct is the truly creative and affirming power, and consciousness acts as a critical and cautioning reaction, in Socrates the instinct becomes the critic, consciousness becomes the creator — truly a monstrous defect. — Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy, Chapter 13

This general idea has been understood in the European classical music traditions for centuries and awareness of it has given the world some of the most refined and whole works of art music. It is only in our post-modern era that we erroneously want to strip everything away from its original meaning and validate poor art by arguing that all that matters is the writer’s own intentions, which nobody can guess or question.

Defenses for Wallpaper Music

The most stalwart wallpaper music apologist is bound at this point to support the previous statement by stating the fact that our modern culture (and even more specifically, that our metal subculture) is very different from that which engendered classical Romantic music. While I consider this argument to be debatable, I will concentrate on the biggest issue that comes out as a result of this reasoning as a whole. This is the idea that because modern artists are free to choose how to express themselves they can pick from any musical-philosophical camp and just smash it together, twist it around in whatever way they see fit or their limited organizational skills and inspiration allows them to, with little or no justification other than their “need” or “right” to express individuality.

Allowing that artists are, indeed, free to choose their means of expression, their music can be rubbish in the context of the language they choose if they attempt to use it in ways it was not meant to be used. Can a previous “musical alphabet” give rise to a new “musical language”? Yes, and this is precisely what jazz and metal (separately and in very different directions, the former separating itself far more from a philosophical perspective while the latter remained akin in spirit) have done with Common Practice Period theoretical knowledge or general concepts.

A “smart” wallpaper apologist remark here is that we at DMU “fetishize” the European classical music outlook. But we do not ask bands to ascribe to the metal language which has explicit ties to that European tradition. If a band does not want to be judged from this perspective, then choose a different set of premises, a different language to speak. I would be very interested in witnessing attempts at using metal instrumentation to play music built on the principles of traditional Indian music. It would not be metal, but it would be a thing of its own with coherent expression.

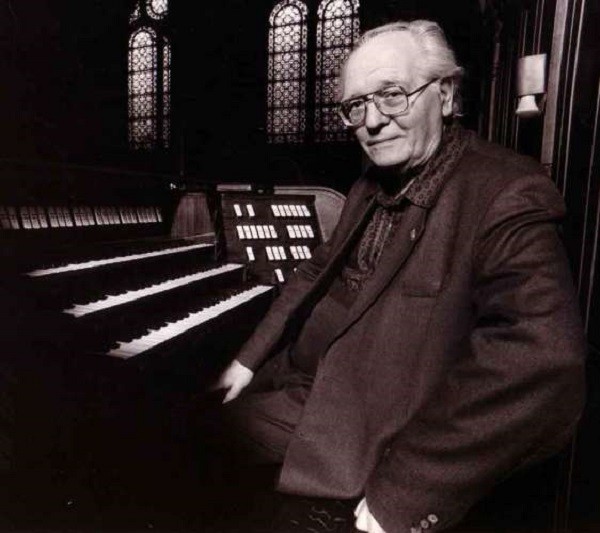

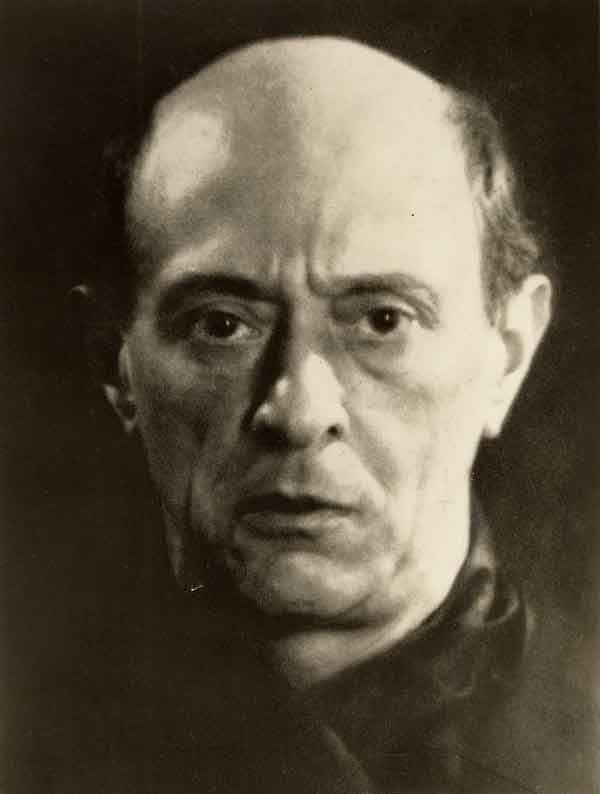

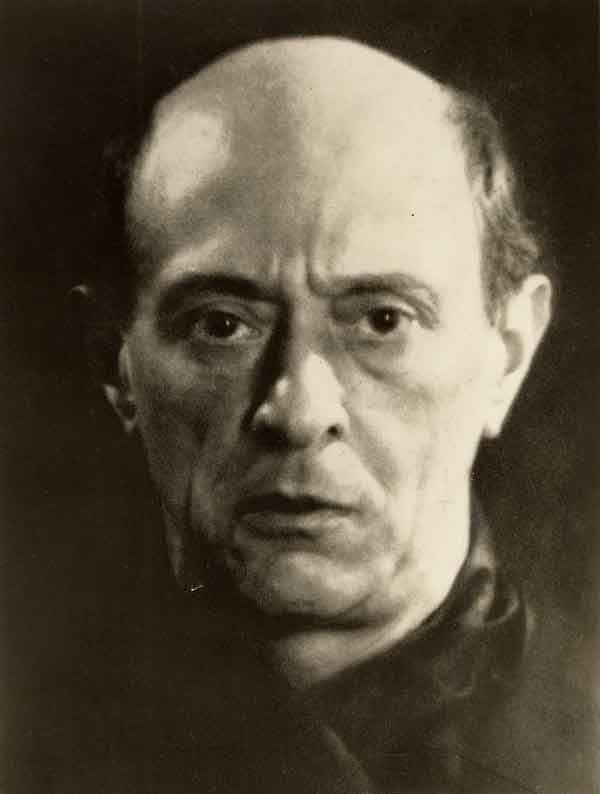

Does it mean that everyone making music has to subscribe to already-existing musical languages and that there is nothing new to be had so that we can only indulge in superficial variations? This is what post-modern short-sightedness would have us believe and in doing so somehow justify the trivial superficiality of the so-called experimental bands. But then you can turn to great composers such as Arnold Schoenberg(1874-1951) and Olivier Messiaen(1908 – 1992) who effectively created brand new musical systems for them to express the music they wanted. They were both world-renowned advanced composition professors, which says a lot about how difficult it is to single-handedly accomplish such a task. Furthermore, as Uri O’Reilly’s article Developmental variation and underground metal implies, defined constraints and limits that guide genres and the languages they speak do not themselves imply a prison for the mind or shackles for creativity, but rather a tool much like a sniper rifle’s scope to reach precise and far-off targets. Bands that build incoherent music out of disparate musical languages or fail to use their chosen language effectively and expect the listener to submit to the purely emotional shock of the music, or worse, listen to exuses and rationalizations to “explain” the art, have missed the point: context is meant to be referred to, much as we expect language to have consistent approximate meaning. To ignore that meaning is communicate with no one, whether in music or the written word.

Defenders of wallpaper music will react in a populist manner and say that all that matters is that one likes the music, and ask rhetorically and spuriously who is to judge music otherwise. To assume that art should have meaning is to judge one subjective experience over another, they say. Some might say that in that case, anything deemed to be wallpaper from a point of view might be seen as meaningful from another. While this may be theoretically true, in application it is the same as claiming that spewing random syllables cannot be labeled as gibberish since they may, in fact, mean something in some hypothetical human language. The next wallpaper apologist complaint here would consist of pointing out that while language has hard and precise meanings (which is actually, not entirely true), music appeals to general emotions and moods and so, if the work accused of being wallpaper achieves some sort of reaction in the listener that produces coherent thought, then it has “meaning”. But this, again, is just the same as the random syllables reminding anyone of something in his own language and thereby acquiring a meaning provided from the outside.

Return to Chalice of Blood Heilig, Heilig, Heilig

Just like Romantic-era critics with knowledgeable background and cultural familiarity with their genres allowed them to make criticisms not only of technical construction (outer traits) but also of character and sense (inner traits) of the classical music of their time, so is the educated metal critic who understands the objective nature and origins of metal endowed with the same capacity to dissect metal music.

A track by track approach to Chalic of Blood Heilig, Heilig, Heilig will illustrate the concept of wallpaper music and reveal its failing as a method of artistic communication.

We start off with “Hoor-Paar-Kraat”, which, if seen as a song or independent piece fails immediately as it consists of a chord progression in four bars in standard time signature played through 1:39 minutes with no variation besides different pick-up and ending percussion patterns, and a background guitar strumming the same chord progression in different ways (more sparsely here, more vehemently there). One is then tempted to see it as just an introduction, a sort of prelude to what is to come.

It is then that we face “Nightside Serpent” whose structure consists of an introductory or main riff followed by two distinct verse riffs. The riffs talk to each other convincingly in their contrast and similarity. They clash against each other in a way that makes one think of the classic of classics, “Transilvanian Hunger”. But while Darkthrone used as little as two riffs per song in that album to create whole sections with functions ranging from intro, to verse to a sort of ramp into meditative climax, only to bring us back to its initial aura, Chalice of Blood’s song is simply that: a main riff, a verse, a second verse. This is simply played two times and brought to an abrupt and meaningless end at the 3:19 minute mark. It is here that we start to suspect that the presumed introductory track may just be a taste of the incompleteness and vacuity of this music.

The third track goes by the title of “Shemot.” It can easily be divided in four parts. The pick-up measures are soft and consist of a strummed chord bent by a whammy bar which applies vibrato at the same time. Then the first of these parts is a Darkthrone-intense section with use of the raw energy of hard-picked tremolo and fast Immortal blast beats. This section dissipates into the second. The texture changes drastically into sparsely strummed chords and mid-paced double-bass drums to the beat of a snare in duple time. We then climb back to the intense texture shown in the second section as a way of climaxing that brings back the riding first riff to function as outro as well. This all happens in 3:18 minutes. The focus here is how much “atmospheric black metal” riffs can they use contrastingly to create shock. Other than that, there is little eloquence to this.

“The Communicants” is probably the most deplorable song in this album with the most obvious wallpaper thinking displayed. The whole song is built by repeating the same slow-moving chord progression of 8 measures from beginning to end. The only thing that signals different points in the piece are the drum patterns and the presence or absence of the vocals. This repeating chord progression is not used as one would see one of the German master composers create vast amounts of content through clever variations and chaconnes, but it literally consists of repeating the exact same music ad nauseam. Or ad 7:11 minutes, to be precise.

Finally, we reach the last inconsequential, empty track named “Transcend the Endless.” In here we are presented with 3:30 minutes worth of the same minimalist black metal approach sans substance.

Albums such as these remind us how little understood monuments such as Transilvanian Hunger really are. The greatness of the classic lies in the careful use of the least number of riffs in arrangements that together with voice and drums created complex structures with cleverly placed articulation points. The minimalism of Darkthrone’s masterpiece is only in how little tools and riffs they used. It is not a minimalism of complexity of thought or construction.

A blatantly simple music which expects emotional shock and some consistency in style to do all its work, Chalice of Blood Helig Helig Helig gives us almost twenty minutes of essentially nothing. Nothing except transient noise.

20 CommentsTags: Black Metal, chalice of blood, wallpaper music