We thinking apes who live through memories of conclusions derived from event change in sense simulacra of the world find ourselves continually going over memory, wondering if what we know now is what we knew then and if it is even real.

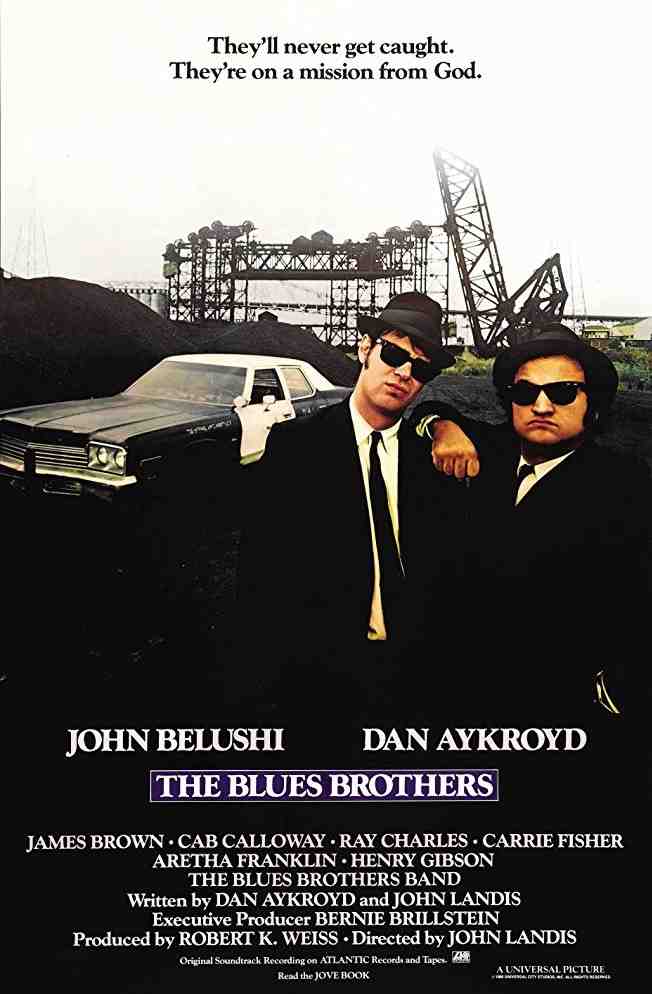

In that vein, it makes sense to sometimes revisit items from the past like The Blues Brothers (1980) which most people in that era would have identified as a really funny movie. It is not, and it sometimes is.

Like most cinema these days, this movie is a cartoon and, because supernatural or extranormal events occur, qualifies as early “capeshit” despite being a comedy. In these cartoons, the traits of people are indicated by their category, which makes for funny stereotype play because like robots, people act out their assigned roles even background events change and make that ludicrous.

It is like a Shakespearian tragedy-comedy in that sense, because people do what they do because of what they are as seen by the audience, so you have maniac cops who will drop everything to chase down a lawbreaker even as that quest waxes Ahabian and ruins everything.

The original capeshit was probably Star Wars (1976) because it combined hard action with magic from a religious realm, so it was no longer constrained to trying to make every element in the story be compatible with known reality. Just add “the force” and suddenly everything is OK.

In The Blues Brothers, two orphans embark on a mission to save their orphanage by singing their favorite blues and motown songs to an audience of morons. This sets off what is ultimately a masterpice of physical comedy that otherwise is not that funny.

Like most postmodern things, it is shot through with the equality mythos; how else do you end up at the idea that form=content except by making everything equal, effectively abolishing content as much as Christianity abolished the physical world in order to embrace a symbolic one? Postmodernity renders everything to symbol, and the form here is not so much the literary pyrotechnics of postmodern fiction but the cartoon-like tendency for each person to be a stereotype of what their character is.

As part of this, there is of course worship of the African and denigration of the redneck American and the “Illinois Nazis,” ironically representing the ACLU-defended march of Frank Colin (née Cohen) through Skokie, famous for its Jewish community. One does not need to defend that stupid act of Jewish Nazi self-hatred to realize that Hollywood is bashing some familiar tin drums here.

Naturally seeing Aretha Franklin, Cab Calloway, Pee-Wee Herman, James Brown, Ray Charles, and John Lee Hooker ham it up in a movie about music is great fun, as is Carrie Fisher’s presaging the overly-attached girlfriend meme in a Romanian version with great psychotic zeal. Mostly however, the audience for this movie was the same as those who would tune in to The Dukes of Hazard, namely people who like slapstick and car crashes.

Like all postmodern things, it converges on a gentle version of the French Revolution. All the misfits — orphans, nerds, geeks, minorities, Christians — join together to overthrow the nasty authority figures and do something fun instead of, you know, going to work, paying taxes, shopping, and watching TV.

In the end, this makes the movie hollow like a cartoon. It is presenting simplistic stuff for simplistic people, and mostly, we watch it for the car crashes and explosions. A more perfect vision of modernity would be hard to find.

Tags: capeshit, film, french revolution narrative, slapstick

The second best cover of Rawhide next to DK!

I wonder if the sequel is as monumental as Caddyshack II and Christmas Vacation II?

If something’s good, I don’t care from what political angle it’s shot. A similar movie “Trading Places” 1983 from the same angle is actually a lot more straight-up entertaining than this forgettable and overrated heap.

As much as I dig the 80’s, it’s impossible that everything was good then, or any era for that matter.

Excellent movie I must have seen 100 times by now.

There are different editions of it, there is the VHS with extended music scenes, and I read the TV edit had different scenes included.

For years, it was THE movie known for crashing the most amount of police cars ever.

No idea if it still holds the record.

Yeah, the “illinois nazi” and the redneck country music scenes are trash.

They did seem funny the first time around when I did not know any better.

The actual Blues Brothers Band was solid, so if anybody that likes early Rolling Stones records, that were more blues than rock, should listen to the two (or is it three?) BB albums.

That car chase scene through the shopping mall destroying everything is still cool;

the only other scene in a movie coming close to it is Tom Green skateboarding away from mall security at the start of “Freddy Got Fingered”

Hi there. At least for me, the entire movie is a vehicle for that one scene, but Mall Car Chase I suppose would’ve been an odd name for the film.

Funny, they were playing this at the brewery recently, and I’d never seen it. It seemed to hit all the marks that the hipsters find are important and I ignored looking up at the screen as much as possible. And I guess it’s funny to the Italians and Irish to make jokes about selling WASP upper class women into slavery.

Watched with my son in the last year & was kinda shocked at how awful I found the film, as I had kinda fond memories of it back when I first saw it as a pre-teen.

Anyway, a list of the greatest Albanians in history:

1) Alexander the Great (goin w the Illyrian theory)

2) Gjergj Kastrioti Skenderbeg

3) Lionel Messi (an Arbëresh brother)

4) John Belushi

X) Jim Belushi should’ve been the one to die young!!!