With the fiftieth anniversary of metal music around the corner, forthcoming years will witness an increase of publications dealing with the history, legacy and defining characteristics of the genre. This could finally resolve the lack of consensus that still exists regarding the definition and origins of heavy metal.

Since its inception, heavy metal has been repeatedly erroneously identified as being a form of rock music. This has led to the mainstream trope that metal is little else than a more aggressive form of rock and that Led Zeppelin originated the genre because they released their debut album the year before Black Sabbath. If metal is to avoid being assimilated by the simpler and more popular genre of rock music, an independent, comprehensive and convincing metal “meta-narrative” needs to rise in the consciousness of listeners, critics and theorists alike.

The first task in such an endeavor is to clarify the origin of metal music. It is important to understand that a new genre can arise from the old without being part of it, but without being entirely separate from it either; in fact, throughout its life, the threat of being absorbed by the original remains high. When we consider the case of Black Sabbath, this distinction becomes clear: their music was very different from what was going on around them, but it was not concieved ex nihilo like the so-called virgin-born savior of the human race. It is only by studying metal within its specific musico-historical context that we can begin to determine its distinctive features, be those musical, ideological or aesthetic.

We can discover the spirit of metal by examining metal’s origins within the musical and cultural milieu of late-1960s Western Europe and the United States. There is much to learn by comparing early heavy metal to it closest musical relatives. It gives hints both about what separated metal from other musical movements at the time, but also what binds them together over the course of history.

Black Sabbath as the Originators of Heavy Metal

There is little consensus about the exact origins of the metal genre. That Black Sabbath founded the genre is clearly the most convincing theory suggested so far. Heavy metal entered public consciousness no later than Friday the 13th in February of 1970 with the release of Black Sabbath’s eponymous debut album. Even though Black Sabbath contains a fair share of songs with elements that would be expelled from the genre as it evolved into purer forms, it is a consistent enough album and, perhaps more importantly, it features one of the most visionary, genre-defining, and all-around excellent compositions in metal history: the monumental “Black Sabbath.” This song perfectly captures the spirit of metal while also laying down large portions of the musical syntax used by metal-bands ever since.

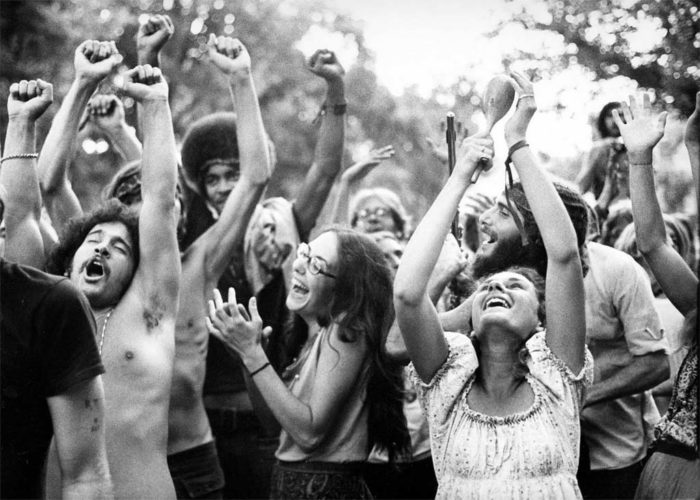

In rejection of the prevailing cultural climate of it time, “Black Sabbath” conjures visions of darkness, morbidity and acute danger draped in a cloak of (probably horror-film-derived) historic/mythological allusions. At the same time, the music and lyrics brings a streak of realism that was largely absent in the drug-induced escapism and flowery fantasies of the hippie movement. Inspired by the music from horror films, of which some members of the band were fans, and stormy classical like Holst’s “Mars” movement from The Planets suite, which was the starter material for one of their classic songs, Black Sabbath mixed the heavy rock of the day with other influences to create an entirely new sound, even if it was not fully realized as what heavy metal would become, leading to the confusion about the origins of metal outside of rock music.

The song is a welcome wake-up call that reminds us that the world is not solely a benign place for humans to indulge in, beautiful on both surface and inner core. Only one can be beautiful, and if heavy metal has a core mythos, it is that when we look at the large picture through dispassionate realistic eyes, we see that what is ugly on the surface often conceals an inner beauty, and what is beautiful on the surface is usually a rotten lie within. Only in rare cases is beauty shared between inner and outer essence, and those are found through a process of violence and chaos that is reflected in the music.

What further separates Black Sabbath from the emasculated “occult-rock” of their times (and later years) is that they played music that matched their vision. There are few songs that better captures both the musical and expressive essence of metal than “Black Sabbath.” Church-bells at midnight, down-tuned, heavily distorted guitars, riffs built from sequences of power chords, palm-muting, the infamous tritone interval, flat seconds, inclination towards modality, war-like drums, terrified cries of anguish and a liquid mass of cthonic bass-tones all contribute to the singular character and the corporeal/spiritual “heaviness” of the music.

“Black Sabbath” also brings to the fore what is arguably the most important compositional element of true metal music, a riff-centered approach where each musical phrase corresponds to its neighbors in cogent musical narrative. No one else was doing this kind of music at the time, and it would take several years — despite the band’s ever-increasing popularity — before the world truly caught up with what Black Sabbath was about. However, it is of vital importance to acknowledge that Tony Iommi and Co. didn’t “invent” all of these musical and compositional techniques in a strict sense. Of course, one could say that the specific components in the music (the riffs, song shapes, idiosyncrasies in playing-techniques) were new, but that misses the point of the argument. What they did was to bring existing musical elements together into a coherent and convincing vision that was indeed wholly original.

Where then, is the roots of metal music to be found, and what differentiated Black Sabbath and later metal from its predecessors and contemporaries? One way of answering these questions is to study the general musical environment from which Black Sabbath emerged through four genres which combined formed its influences: heavy rock, progressive rock, punk music and electronic topographic ambient, which joined with horror soundtracks and blues, jazz and folk influences to provide the palette of techniques from which Black Sabbath drew in order to finalize its thunderous vision.

Emergence From Psychedelic Rock

As some of you may know, Black Sabbath was originally founded in 1968 with the slightly less ominous name The Polka Tulk Blues Band. They began playing an earthy form of blues-rock, later changing the band name to Earth, and then after some kind of epiphany to Black Sabbath. Judging from the original name of the band, it seems likely that their early music was more in line with the tastes and spirit of the sixties. What is more significant though is that they reacted against the prevailing cultural and musical climate when they morphed into Black Sabbath. That explains why their music carries many elements of rock, while at the same time clearly transcending it.

The mid-to-late 1960s is regularly heralded as the “Golden Age” of rock music. Whether one likes the music in question (or extra-musical implications that can be derived from it) or not, it’s difficult to argue against its lasting influence on rock music in general. Just about everything produced under the moniker of rock since then are derivates of the Psychedelic Era of rock (1966-1969). The surface might’ve changed a little, but it’s still the same old music when stripped to the core.

The sixties was a time of upheaval on several fronts simultaneously, including social, cultural and political. This was the time of the so-called counterculture: a loosely tied movement that spread throughout the Western World from the cosmopolitan urban centers of London and San Francisco. The spirit of the counterculture is clearly reflected in the music of the period. In fact, psychedelic rock was arguably the most important factor in the formation of the counterculture, as it provided its proponents with a sense of communal identity and area for expression.

By building on the template provided by the early rock’n’roll, r&b and beat groups, psychedelic rock extended the boundaries of rock music significantly by drawing on a host of external musical and extra-musical sources. Drugs, religion, quasi-Eastern philosophy, Marxism, and technology collided with 50s rock, blues, jazz, folk music, Western/Eastern Classical, avantgarde electronics and pretty much anything musicians could get their hands on. Records companies, of course, realized that there was money to be made and became eager to provide a market for a changing market. This strange combination of experimentation and financial opulence resulted in considerable artistic freedom for musicians, who could now pursue with producing music that went beyond the strict forms of early rock’n’roll.

Songs were often drawn-out and featured lengthy instrumental- and solo-sections, sometimes known as “jams” or “freak-outs” for their tendency to be times when the music got nearly out of hand. These sections were often improvisational to some extent, featuring highly repetitive ostinatos provided by the bass over which the other musicians could explore the world of sounds. The droning quality of the music combined with heavy drug-intake to produce a feeling of suspended time and place in the mind of the listener.

Despite its eclectic basis and exploratory spirit, psychedelic rock was clearly a rock genre in terms of deep structure and syntax. The inclusion of musical elements foreign to rock seldom went beyond surface-level addition, giving the music and air of exoticism. Moreover, psychedelic rock was definitely regarded as unified style and movement within rock by its proponents. One can see the psychedelic era as a musical/cultural nexus-point, the last unified “youth”-movement before it branched of into a multitude of sub-genres and -cultures.

In his excellent book on progressive rock Rocking the Classics, Edward Macan identifies three distinct branches (or “wings” in the words of the author) of psychedelic rock which would come to play important, although different parts in the formation of subsequent musical genres that came to fruition in the early 1970s. The second and third branches were predominantly instrumental in the creation of progressive rock, electronic music, jazz-rock/fusion, etc. and will be discussed below in connection to those genres. Most important in the context of metal however is Macan’s first branch of psychedelic rock, to which we now will turn.

Thread 1: Heavy Rock

The first branch in Macan’s review of the psychedelic rock movement — also known as heavy rock — is represented by groups such as Cream, The Jimi Hendrix Experience and the Yardbirds. These bands hooked up with the blues-derived, riff-based approach of The Rolling Stones and took it to the next level in terms of intensity and experimentation. Song structures were usually kept rudimentary with repetitive guitar-riffs traversing over staple blues progressions, but regularly extended beyond the time-limits of a standard rock-song. Such a skeletal approach to songwriting gave ample opportunity for the musicians to indulge in instrumental ensemble workouts and soloing. It also provided enough room to “rock out” when needed, an aspect further intensified by the employment of power chords in combination with gratifying distortion and feedback, shouted vocals and heavy rhythm section. As a result, the sound of heavy rock was very direct, yet at the same time exploratory.

A major split occurred during the late 1960s when heavy rock divided into two major strands of music: hard rock and metal. The former includes bands like Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple, who expanded upon the template of the original heavy rock bands. Black Sabbath on the other hand became the founders of the metal genre, a different type of heavy music that was less dependent on the forms, syntaxes, aesthetics and lyrical topics of rock’n’roll. This view is still considered as somewhat controversial, especially in those circles who regard metal as little else than a noisier form of rock. However, viewing the music of Black Sabbath and their adherents as a distinct phenomenon does not decimate the importance of heavy rock in the formation of the metal genre.

Case Study: Cream – “Sunshine of Your Love”, from the album Disraeli Gears (1967)

When exploring the relationship between heavy rock and metal, there is no better place to start than with the music of Cream. They are one of the most influential and popular of heavy rock bands of all time and their music provide an important part in the puzzle that led to the creation of metal music. Cream was founded in the UK by the reputable and virtuosic blues and jazz musicians Eric Clapton (guitar/backing vocals), Jack Bruce (bass/vocals) and Ginger Baker (drums), who had been previously working within a rock/blues/jazz-context in bands like The Yardbirds, The Bluesbreakers and the Graham Band Organisation.

Not surprisingly, Cream’s brand of rock was heavily inflected by both blues and jazz music. However, being a psychedelic rock band their output extended over a wide range of other styles. At minimum, it is possible to identify at least five different types of songs in their repertoire: electric reinterpretations of blues staples in some cases extended to large-scale instrumental improvisations (“Spoonful, “Born Under a Bad Sign”, etc.), self-penned blues rock numbers, often using the twelve-bar blues template (“Strange Brew”), pop-oriented psychedelic rock (“I Feel Free”), experimental rock-songs (“White Room”) and finally bluesy rock-pieces based on a repeated riff-pattern used as a motivic figure (“Sunshine of Your Love”). It’s the fifth and last type that is most important in the context of this article, as these songs feature various techniques that would later re-surface in modified form in the music of Black Sabbath.

Even though it sounds tame by today’s standards, “Sunshine of Your Love” is an enjoyable song that gives clues regarding the peculiarities of early metal. The song was an instant success among both fans and musicians alike at the time of its release, and features a signature riff that counts among the most influential moments in rock history. Like most of Cream’s material, “Sunshine of Your Love” incorporates elements of blues in an electrified rock context. The song is based on a modified form of a repeated twenty-four bar blues pattern in 4/4, which functions like an ordinary twelve bar blues except that it doubles the amount of measures.

Most central is the driving, minor blues pentatonic verse riff, which constitutes the song’s hook and “essence.” Cream’s riff-based compositional approach diverges from the standard pop and rock custom of placing the signature melody/hook — often supplied by the vocalist — above the foundation of guitar/bass/drums and letting it be the central focus of the song. On “Sunshine of Your Love,” the riff is doubled by bass and guitar, the former laying down a steady foundation while the latter supplies interesting variations on the melodic figure. Placing the riff at the center of the stage, however, requires that one can write good riffs. Cream’s method for riff-writing seem to have been to distill old blues numbers down to a single phrase, which becomes the signature instrumental figure of the song. Add to this Eric Clapton’s light palm-muting technique, mix of power and barred chords in combination with just the right amount distortion to understand how a simple succession of tones can come alive in three dimensions. While metal bands would turn away from the blues early on, they did embrace the Cream method of writing riffs that define the essence of a song.

Another interesting parallel between the riffing of heavy rock vis-a-vis metal bands concerns the use of the flattened fifth interval. As mentioned above, Cream employed what is often referred to as the “blues scale”: a hexatonic scale which adds a ♭5th to the minor pentatonic scale. The flattened fifth, more known as the tritone or “devil’s interval” among metalheads, adds to the sad or “blue” character of blues music. Metal bands on the other hand exploits the dissonant qualities of the tritone to make the music sound dark, ominous and sinister. The reason why the same interval is experienced differently in blues and metal partly has to do with how the flattened fifth is used. In the blues, the flattened fifth tends to be employed as a passing note to give the music a sad and mournful character. It doesn’t feature as a note on which the music “rests.” In metal however, the same interval takes the center stage. Just compare the main riffs of “Sunshine of Your Love” and “Black Sabbath” to understand the importance of the flattened fifth in both genres and how they differ from each other in terms of technique and feel.

Cream’s choice to play blues-derived rock as a three-piece forced them into a relatively limited musical setting, which in turn required a great deal of effort and imagination to pull off successfully. Luckily, they had a most competent and inventive percussionist in Ginger Baker. It is his insistent, deceptively simple drumming in combination with the signature riff that makes “Sunshine of Your Love” stand out among millions of similar tunes. Rather than playing a typical rock back beat he settles for a quasi-tribal rhythmic pattern using mainly toms. He accents beat 1 and 3 instead of 2 and 4, which fits perfectly with the main riff and lends the song a propulsive, almost war-like character. Moreover, Baker’s drumming reduces the stupefying bounciness inherent to much rock music, a feature that would become an important component in metal music as well.

Baker was also one of the earliest proponents of double bass drum-kits in rock, a technique he probably picked up via jazz. There’s only a short sequence of double bass-drumming right before the end of “Sunshine of Your Love”, but he uses it more prominently on tracks like “Toad.” Although he personally seem to have detested everything hard rock and heavy metal, Ginger Baker was clearly an inspirational figure in the development of metal drumming.

Differences between heavy rock and metal also comes to the fore in the fields of aesthetics, lyrical subjects and structure. The first two can be summed up quickly: Cream’s lyrics and overall extra-musical features clearly belongs within the psychedelic tradition that metal revolted against by turning towards a gothic/mythological/realist-mindset. A similar argument can be raised regarding structure. Cream plays rock and employs the compositional tools of a rock band. Even if their driving riffs and employment of the blues progression lends their songs a feeling of forward momentum, it is only illusory. “Sunshine of Your Love” doesn’t “go anywhere” because it is circular in nature. Variations do occur in terms of riff shape, but it is the blues progression that dictates how the riff is modified. This can be contrasted to the way metal bands let content shape form, and how riffs are subsequently modified and glued together to form an organic, narrative-like structure. Herein lies one of the central explanations as to why metal should be regarded as a musical genre distinct from rock. That doesn’t mean that Cream’s music isn’t enjoyable, but the structural predictability inherited from earlier rock does impose limits on its lasting value.

Thread 2: Progressive Rock

Like heavy rock, progressive rock (colloquially abbreviated as “prog” or “prog-rock”) has its roots in the psychedelic era. According to Macan, progressive rock sprung out of what he identifies as the third branch of psychedelic rock, represented by the exploratory, late-1960s works of The Beatles, The Nice, Pink Floyd, Procol Harum and The Moody Blues. The original progressive rock bands developed a similarly eclectic and experimental approach to rock, but went deeper in their integration of elements previously foreign to rock music. Thus, one can find elements from sources as diverse as Western and Indian Classical, avantgarde electronics, folk, jazz, blues, pre-1950s popular genres, metal and choral music in progressive rock, sometimes several of them within a single work. However, whereas most psychedelic bands added new elements on top of their (often conventional) rock music, progressive groups regularly attempted to forge influences into the core of the compositions.

As a result of this thorough musical renovation, progressive rock significantly expanded the previously established musical vocabulary of rock in almost every field possible, including: melody, harmony, rhythm, timbre, instrumentation, instrumental technique, production and compositional form. Moreover, many bands caught up on the notion of music as concept which had become popularized by The Beatles with their Sgt Peppers-album some years earlier. This would over time become one of the hallmarks of the genre. Even though some would say it was for the worse, the fact that conceptual ideas took on an important role in relation to the music did in some cases result in more interesting and stringent music.

Before proceeding, there is one issue that needs to be raised here in relation to defining progressive rock. When ransacking existing literature dealing with progressive rock one is struck by the overwhelming focus on English acts, usually followed by discussions regarding the supposed “English-ness” of the genre. While it is true that progressive rock as we know it originated on the British Isles as an offspring of (mostly) English psychedelia, and that the original styles of UK bands have been aped to the point of farce, it is well-worth noticing that the genre contains music of enormous variety and place of origin. In contrast to Macan’s and others who appears to see the genre as a predominately English phenomenon, others have suggested a more broad and fluid demarcation that would also include, for example, European and North American acts as diverse as Popol Vuh, Can, Magma, Träd Gräs och Stenar and Mahavishnu Orchestra. Some of these groups have almost completely left rock music behind altogether; for example it is very difficult to find any traces of Chuck Berry or The Rolling Stones in Tangerine Dream’s monumental third album Zeit. However, we can leave this dispute behind for the time being, since it is above all the output of 1970s English groups such as Genesis, King Crimson and Yes that has hold the longest and most thorough-going influence on metal.

One can find many parallels — be it purely musical, aesthetic or lyrical — between progressive rock and metal music. On a general level, there are two correlations that are particularly striking: artistic outlook and compositional method. Progressive rock and metal share an artistic outlook that is thoroughly Romantic. Each exhibit a burning concern for mythology, fantasy, transcendence and heroism which runs like a red thread throughout respective musical output of both genres. While it should be acknowledged in connection to this that many progressive rock bands were more closely entrenched in the ideology of the counterculture that metal bands like Black Sabbath revolted against, it would be a misconception to label all progressive rock as hopelessly utopian. The music of King Crimson, Magma or Van der Graaf Generator hardly classifies as particularly escapist or “flowery.” Even the occasionally whimsical and fantastic streak in bands like Genesis, Gentle Giant and Yes often hides a darker undercurrent that only becomes stronger because of the contrast created between antithetical conceptions of light and darkness or beauty and monstrosity. These are not alien concept to metal music, just consider the paradoxical of black metal, where sublime beauty and unfiltered ugliness go hand in hand.

The major compositional contribution that progressive rock handed down to metal concerns structure, although not so much form as a general attitude towards creating compositions that eschews conventional rock-derived song structures in favor of a narrative approach. The best works created within progressive rock often displays a high sophistication in the form of extended song forms. This should not be mistaken for “classical song structures,” as is often done. Although there are cases where progressive rock bands utilize classical techniques like fugal structures, this writer is yet to find a progressive rock piece confirms to the principles of a sonata form. However, progressive rock did appropriate ideas connected to narrative composition and extended song format from Western classical music, and this would over time become one of the more important characteristics of the genre at its most excellent. When Black Sabbath formed back in the late 1960s, it is highly probable that they were subjected to and inspired by the earliest progressive rock music. Their song-writing methods were obviously different, but their way of forging riffs into engaging musical stories have much in common with the compositional ambitions inherent to progressive rock. This affinity towards narrative structures — to adapt form to content — is observable in later underground metal genres such as death and black metal as well. So despite the observation that progressive rock had become creatively barren by the mid-1970s, its legacy lives on to this day.

Case Study: Genesis (1970-1974)

Before transforming into an immensely successful and artistically empty pop band, Genesis used to be counted among the “big six” among UK progressive rock (the others being Emerson Lake and Palmer, Gentle Giant, Jethro Tull, King Crimson and Yes). During the early 1970s they produced a string of high-quality albums featuring a very distinctive sound that, ironically enough, would spawned hundreds of copycat bands around the globe. It wouldn’t be out of place to announce Genesis as one of the more characteristically “English” bands of the bunch, although it is a difficult adjective to pin down. Let’s just say that it is felt both musically and in the atmosphere, humor and general frame of reference evoked by the band.

Genesis’ early style (excluding their first release which was basically a pop-oriented album) helped define progressive rock and displays many of the genres general characteristics. Their stylistic repertoire reached over folk, pop, psychedelic rock, classical music, soul and even a bit of hard rock/metal when needed, frequently channeled into extended songs that evolved like short tales told in with a heigthened sense of theatricalism that blended both pastoral and more sinister mental landscapes. Lyrical topics recurrently returned to medievalism, folk-tales and mythology, filtered through a peculiar mix of melancholy, humor and sentimental morbidity.

Not surprisingly, Genesis counted among those progressive bands that received the most rabid vitriol from critics who regarded the band’s music and overall expression as overbearingly pompous and contrived. This hostility was probably not just grounded in the actual music, it had much to do with their immense popularity. However, accusations of “pretentiousness” seldom hold up well. Concerning the supposedly obstinate complexity of the band’s music, one can easily repudiate this accusation by pointing out that neither of the band members displayed any visible signs of instrumental virtuosity (with the possible exception of drummer Phil Collins, but he never really overplayed his parts).

On the contrary, Genesis’ music is quite “light”, and whatever complexity is found in their output has more to do with the bands ability to compose material that demands extensive dialogue between musicians rather than them going off on self-indulgent expeditions. Counterarguments against musical contrivance are easily supplied as well, because underneath the fey-like surface of large portion of the band’s output hides a dark subcontinent inhabited by shady, macabre and sometimes perverse entities that can only be glimpsed at through layers of proxies. Moreover, the music is quite aggressive and dark at times but not in such an outspoken manner as in the discordant music of King Crimson or in metal for that matter.

In addition to more explicit semblances such as the use of exploding guitar solos and battering drums, Genesis influenced many of the older metal musicians in a very direct manner through their way of writing long, winding songs that spoke to the listener as an ongoing story. The band became very skilled at turning basic, pop-structured material into flowing narratives through the addition of introductions, bridge-sections, solos, outros, etc. Thus, a song could feature as its core relatively simple verse/chorus-material that was then developed through variations and interstitials. An early example is “The Knife” from their second album Trespass (1970). The song provides tension and release by contrasting a build-up verse with galloping shuffle-rhythms and guitar power chords against a contrasting chorus with a fanfare-like melody traversing over evenly divided quarter notes. To grant variation and a sense of development to this juxtaposition, the verse/choir-pair is complemented by complementary sections that makes the song feel like it has a direction beyond simple repetition. A valid comparison can be made to Iron Maiden’s “Phantom of the Opera,” which develops according to a similar pattern. Steve Harris has recurrently expressed his admiration of classic Genesis, and their influence on Harris’ songwriting is unmistakable.

Occasionally Genesis also composed songs that unfolded in a linear fashion. “The Musical Box” from Nursery Cryme (1971) illustrates this procedure and also affords an insight into the previously mentioned “dark side” of Genesis. A spectral twelve-string guitar introduction sets the mood for the piece. Then, the listener is led through several sections of varying mood and character, following the twists and turns in the bizarre story-line narrated by Peter Gabriel. Every shift in dynamics, instrumentation etc serves a purpose in contributing to the narrative. So, even though the music and story may be a bit too much for some listeners, it is not arbitrary or self-indulgent in the sense critics tend to use the term.

Thread 3: Electronic Music

Using the words “electronic” and “music” to christen a musical genre is problematic and invites confusion since the name suggests a definition based exclusively on choice of instrumentation. If that would be the case, the genre would have to include any musical piece that is performed with the aid of electronic instruments. Would Karl-Heinz Stockhausen have enjoyed being lumped together with the most banal popular music en vogue? Probably not. So in order to avoid misunderstandings another term will be offered here together with a demarcation relevant to the main subject of this article.

When speaking of electronic music’s influence on metal, there are five European groups/artists that deserve extra attention: Brian Eno, Kraftwerk, Klaus Schultze, Tangerine Dream and Vangelis. All of them began utilizing electronic devices at some point during the late 1960s/early 1970s within what was essentially a progressive rock context. Therefore, this writer suggest that the less common term “progressive electronic” should be used as an over-arching nomenclature for the music of these artists. Some will probably object to this and point out that Kraftwerk produced synth-pop or that Brian Eno invented ambient music. But a wider “meta-genre” based on relevant historical and musical interconnections, much like progressive rock above, does allow a greater deal of flexibility that could also encompass later, more refined works by Kraftwerk et al. Also, the early, highly diverse and influential works of the artists in question are better suited to a broad definition.

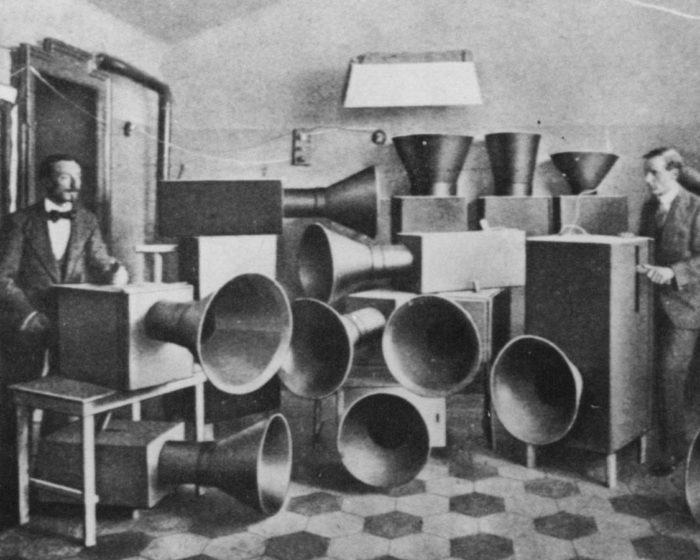

So, in order to track down possible influences on metal music we need once again to revisit the creatively fertile era of the early 1970s, when electronic instruments began to play an increasingly important role in music making. Electronic devices like the Telharmonium had already been used in concert as early as 1906, but these technological monstrosities were very exclusive and didn’t have the same impact as later instruments such as the Mellotron, Moog or VCS3 synthesizer. It would take until the late 1960s before electronic instruments began to show up regularly in popular music, perhaps most notoriously in the music of the Beatles. It was primarily within progressive rock that these instruments came to the fore, and to such an extent that the developmental trajectory of the genre went hand in hand with subsequent inventions in the field of electronic instruments.

That progressive electronic music sprung out of progressive rock can be confirmed by observing early works by the pioneering artists mentioned above. Brian Eno was a member of the art rock group Roxy Music and much of their appeal can be attributed to him. What Eno did was that he processed the instrumental output of the other members through a VCS3 synthesizer coupled with extensive use of tape loops. Tangerine Dream, featuring Klaus Schultze in their early incarnation, began as an experimental “free-rock” band heavily influenced by Pink Floyd before turning towards more electronically tinged sonic landscapes. The Greek musician/composer Vangelis worked with the strange and occasionally excellent psych-prog band Aphrodite’s Child. The early music of Kraftwerk, who were then known as Organisation, blended rock music with avant-garde tendencies into hazy clusters of noise and melting psychedelia far from the frigid tendencies of their later works.

The transition from progressive rock into what would become progressive electronic did not happen over night, and many early releases feature both conventional rock and electronic instrumentation. But the gradual adoption of synthesizers, tape recorders, sequencers, keyboards and other electronic devices had an enormous effect on the music. Decriers sometimes attempt to invalidate electronic music wholesale with the assumption that such music requires little or no skill to perform: “You only push a button, and that’s it!” This is as far from reality as one could get, especially in regard to the original progressive electronic music. Early synthesizers were notoriously difficult to operate and suffered from regular breakdowns, both in the studio and during concert performances. Even experienced musicians within the genre have admitted that it was often the instruments that dictated the course of their musical development and not vice-versa. However, those artists who endured the hardships associated with the employment of, for example, an early Moog modular synthesizer or a Mellotron often went on to create music that turned previous musical conventions — especially those of rock — completely upside down. This musical revolution was not restricted to the interconnected fields of instrumentation and timbre, it also included new approaches to rhythm, melody, instrumental hierarchy, song structure and, one could say, the general character of the music.

There is much to say about progressive electronic music’s connection to metal, both in terms of direct and indirect influences. More explicit examples includes Black Sabbath’s addition of a Moog synthesizer on 1973’s Sabbath Bloody Sabbath (performed by Rick Wakeman of the progressive rock band Yes), the numerous keyboard-heavy instrumental intros common all sorts of metal genres (ex-Tangerine Dream member Conrad Schnitzler did one for Mayhem’s Deathcrush) and the customary inclusion of keyboards and synthesizers in many forms of black metal (sometimes even antiquities like the Mellotron). The legacy of German electronic music also shows up in many electronic/ambient projects created by black metal musicians (Fenriz’ Neptune Towers-albums are a clear tribute to Klaus Schulze and Varg Vikernes has expressed his admiration of Tangerine Dream and Kraftwerk). And let’s not forget to mention the possibility of a Vangelis-influence on Rob Darken. His later music in Graveland and Lord Wind bears similarities to the rhythms, melodies and vocal arrangements heard on the B-side of Vangelis’ masterpiece Heaven and Hell (1975).

More subtle, and perhaps indirect influential patterns are also to be found. For example, electronic bands developed alternative approaches to rhythm that somehow found its way into metal music. The introduction of sequencers in the 1970s allowed musicians to generate repeating rhythmic and/or melodic patterns from sequences of tones with an unprecedented degree of exactitude. These could also be manipulated in real-time to produce cyclic patterns, etc. This affected the role of rhythm in music, although in different ways depending on the aim of the musician. A steady, throbbing pulse can be used to both highlight and downplay a rhythmic pattern, something that Kraftwerk were clearly aware of, to give one example.

In stark contrast to the increased popularity of sequencer-driven rhythms and melodic patterns, we can observe an almost complete absence of discernible rhythms and melodies in some forms of progressive electronic music. The absence of conventional musical elements sometimes made for difficult listening, as it required the listener to observe and respond to abstract musical landscapes built primarily out of shifting layers of sonic textures. This approach to musical creation provided a foundation for the emergence of ambient music, whereas the sequencer-driven, melody-oriented type of electronic music discussed above led to the creation of synth-pop and many other related genres. It appears as highly possible that both strands of progressive electronic music played important parts in forming the language of modern black metal, where texture, rhythm and melody often takes on different roles than what is common in rock music as well as other forms of metal music.

Another parallel between progressive electronic music, progressive rock and metal concerns the way artists treat the compositional relationship between form and content. Although song-forms differ significantly from genre to genre, they share a general compositional methodology in which the form of a musical piece is adjusted to the actual content rather than a pre-disposed structural template. This observation points towards a deeper connection between artists like Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Thorns and Burzum — an assumption that can be further strengthened by consulting interviews with members of the original Norwegian black metal scene.

Case Study: Tangerine Dream

The ensuing proliferation of English and Anglo-American psychedelic rock across the globe in the late 1960s gave rise to a host of local variants, each responding and reacting in their own ways to the source material. France, Sweden and Italy, even South American countries like Argentina cultivated regional and highly idiosyncratic takes on psychedelic, and later progressive rock. The most important developments in the context of electronic music took place in West Germany under the nebulous catch-all-term krautrock. 1970s German experimental rock was in many ways more methodologically and expressively adventurous and outlandish compared to its UK counterpart, not least in terms of song structure, improvisation and adoption of electronic instruments and devices. It was in this context that the West Berlin-based Tangerine Dream began developing their own brand progressive electronic music.

Much like Genesis, Tangerine Dream began activities in the late 1960s and produced their most worthwhile music during the early stages of their career, after which they turned towards an increasingly commercial and cheesy expression. The sheer volume and variety of their output makes it difficult to make general statements about their career, but one cannot ignore the close ties between the contemporaneous developments within the field of electronics and the music of Tangerine Dream. The shifting instrumentation and subsequent mastering — or failure to do so — of whatever electronic devices they had access to at any given recording session had a substantial impact on the band’s musical process. This relationship becomes evident when observing one of their most influential and distinctive albums: Zeit (1972).

Tangerine Dream’s third album Zeit is something of an anomaly in that it lacks any clear musical predecessors or successors. The album seems to exist outside of time and space, since neither the output of Tangerine Dream or any other artists — save perhaps for Klaus Schulze’s Irrlicht released the same year — approximates what is being expressed on Zeit. One way of approaching the strangeness of Zeit is by locating it in the creative history of Tangerine Dream to understand the circumstances under which album was conceived.

In 1970 Tangerine Dream released their somewhat misleadingly christened debut Electronic Meditation (the album featured mostly standard rock instrumentation handled in a manner far from meditative). It is a gratifyingly discordant recording, yet seems more like an attempt to obliterate rock conventions than transcending them as the allusive song-titles and artwork suggests. The sophomore release Alpha Centuari (1971) saw the band moving towards a more expansive sound similar to the synthesizer-soaked space rock of Ummagumma-era Pink Floyd. It is a great and considerably more listenable album than Electronic Meditation, featuring excellent drumming courtesy of Chris Franke, but stayed more or less within the boundaries already explored by the Floyds. Then came Zeit, a monumental double album of infinite proportions with zero traces of anything remotely resembling rock music.

Eschewing rock instrumentation and syntax alike in favor of an abstract, predominately electronic sonic panorama, Zeit is not an easy listen. Its almost complete lack of rhythm, melody, harmony or conventional song-structures seems to have been a direct result of artistic choices and availability of electronic equipment. For example, the band’s decision to record the album without any form of percussion coupled with the inability of the VCS3-synthesizer — used extensively on Zeit — to produce discernible melodic material forced the band towards a more texture-oriented approach of bending amorphous musical phrases out of pure sound.

Consequently, on Zeit Tangerine Dream managed to avoid rock practices and effectively lay down the groundwork for the electronic ambient genre. But more importantly, the band brought something new to the table in the form of layered textures shaped into abstract compositions, promising immense rewards for those listeners who can muster the required concentration and imagination to endure. The music do threaten on occasions to implode by its sheer heaviness, but somehow manages not to by grace of its consistent and contemplative character. The lack of conventional musical “anchorings” only adds to the vastness of the outer and inner spaces conjured on the four 20-minute tracks, all of which suggests a sensation of drifting off into an unfathomable universe.

Although Kraftwerk remains the epitome of German electronic music, Tangerine Dream have played — and continues to do so — a vital role in the formation of electronic-based musical forms, not least ambient and its many offspring. Moreover, although it may seem like a far-fetched claim, Tangerine Dream’s 1970s output exhibits affinities with underground forms of metal — especially black metal — and most probably influenced the same. While Tangerine Dream’s work probably didn’t have a major impact on the earliest of metal music, their records produced during approximately 1971 to 1977 embody many of the principal characteristics of progressive electronic music that would later spill into black metal: the otherworldly vibe, non human-centered cosmic-romantic outlook, predilection towards texture, organic/abstract musical phrases, hypnotic rhythms and extended songs coupled with narrative/ambient compositional approaches.

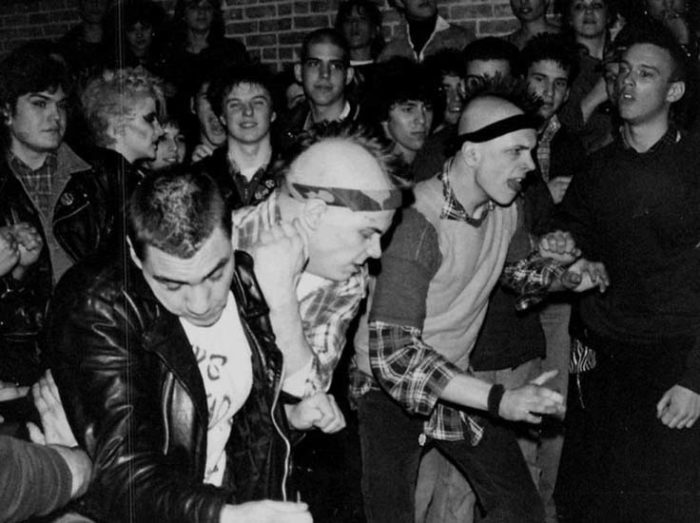

Thread 4: Punk

The relationship between metal and punk has always been ambiguous, but their mutual interdependence can’t be denied. However, just like metal, the mainstreamed history of punk is marred by confusion and misconceptions which makes it difficult to come to terms with the legacy of the genre. Most people assume punk came into existence in the UK around 1976, when it has actually been around approximately since the dawn of metal, perhaps even longer. Moreover, the first steps towards the formation of punk took place in the United States at the end of the 1960s as yet another mutant offspring of psychedelic rock. It is not an easy task to draw the line between what should count as punk and proto-punk, but it would be even more difficult to not judge the late 1960s recordings of The Stooges as a clear embodiment of what would become the building blocks of the punk genre.

Another common misunderstanding about punk music and its part in popular music concerns its postulated hostility towards the three other genres under consideration here, especially progressive rock. While punk surely represented some form of reaction against the increasingly gargantuan and pompous rock antics of the 1970s, it actually has something very important — arguably the most important legacy of punk — in common with original progressive rock movement, namely the willingness to throw over and transcend the established rock paradigm. Just like any other aspiring musician in the early 1970s, many punks could probably sense the walls of commodification and propaganda closing in, but evidently chose a different course of action. Progressive rock went for an extension of rock’s musical vocabulary as a way to move beyond the inherent limitations of its parental genre, punk went the other way. Punk music thus represents an attempt to transform rock by reducing the genre beyond its basest forms. In addition, it introduced the vocabulary of power chords and constant, almost ambient drumming that metal would later incorporate.

Unfortunately the reductionist nature of punk would also become the bane of the genre, as it is easy music to compose and produce. It didn’t take long before the market was saturated with exceptionally moronic releases, most sounding like angry rock’n’roll “with a message.” For many listeners — particularly those coming from a metal background — punk didn’t get seriously interesting until hardcore punk came around with decidedly anti-rock and visionary music produced by artists like Discharge and Amebix. The influence of hardcore punk on underground metal is so vast that it is difficult to estimate if we would be listening to classic black and death metal as we know it if it hadn’t been for the innovations pioneered by punk artists. The same could be said for earlier styles like NWOBHM as well, where punk provided a necessary spark to ignite a renaissance of the increasingly dull genre that was 1970s heavy metal.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BJIqnXTqg8I

Case Study: The Stooges – “I Wanna be Your Dog”

Formed in 1967 and releasing their debut album in 1969, Michigan’s The Stooges (originally referred to as The Psychedelic Stooges) counts among the earliest bands to stylistically approximate what would later be known as punk, or punk rock. Their early career bears semblance to that of Black Sabbath in the sense that they more or less single-handedly defined the core features of a genre still to be officially recognized. Stripped down song structures comprised of simple yet effective guitar riffs over a driving rhythm section with strobing bass notes is combined with a confrontational presence of sacrilege, sarcasm and violence. In many ways, The Stooges embodies both the virtues and vices of the genre.

The music is intense, honest and prophetic in its unfiltered expression of modern decay but at the same time the impact is lessened by its focus on shock and predilection towards a fatalist’s view of nihilism. Of course, the latter could as well be seen as an extension or logical conclusion arising from the horror and downfall felt in the actual music. Either way, The Stooges managed to put together several classic tracks that still stands up well against later works in the genre. Although the best material by the band is definitely to be found on their second album Fun House (1971), “I Wanna Be Your Dog” from their self-titled, desperately uneven debut serves as a proper example of primal punk in its clearest expression.

Conclusion

It is certainly not an easy task to piece together a convincing narrative of metal’s origins, and this survey should rather be viewed as an entry-level attempt than a definitive statement. This study of the musical milieu out of which metal arose in combination with references to related genres can hopefully give clues regarding many particularities of the genre, but in order to get a clearer view what makes metal distinctive would require a closer look at what separates metal its peers.

To go one step further and attempt to capture the essence — be it musical, cultural, ideological or even spiritual — of metal music, then there’s a lot of more work to do. On the other hand, is that really something that need to be done? The music is already there and it obviously affects people whether or not someone tries to explain it. But be vary, there are forces out there who are more than willing to hijack this much beloved music for their own purposes, something that is being done to an increasingly large extent at this day.

Tags: Ambient, article, black sabbath, cream, electronic, Genesis, hard rock, Heavy Metal, heavy metal history, heavy rock, metal history, origins of heavy metal, progressive electronic music, progressive rock, proto-metal, psychedelic rock, punk, tangerine dream, the stooges

The first true metal band was The Beatles. Listen to “helter skelter” \m/

NO!

The most overrated music in history is The Beatles.

No joke. Talk about a band who “just got lucky.”

Baroque era music is the first true metal.

I’m looking forward to reading this completely but I probably won’t find the time to do so before Saturday.

An early remark (as this keeps making will-o-wisp like appearances): The real ‘horror movie’ story (I can probably find the source in one of the Sabbath album liner notes around here) was Ozzy Osbourne observing a large number of people either entering or leaving a horror movie cinema and suggesting something like “Isn’t it crazy that all these people pay money to watch scary movies? Can’t we make scary music?” to Tony Iommi.

Take your time. I’ve read something like that (the horror film-anecdote) as well, probably in the liner-notes to one of their albums. IIRC it also had something to do with the movie “Black Sabbath” by Mario Bava, not sure though.

This was an informative and well-thought out article. I enjoyed it immensely.

I haven’t read through all this and not sure I want to wade through a case history of Genesis but I think it’s suffice to say that the defining feature of heavy metal, as defined by Black Sabbath and pioneered intermittently by Cream and a few others, was the elimination of the backbeat, i.e. the roving roving bassline so common in blues/pop/psych/jazz/country. In it’s place the bassist simply follows the guitar root notes. This creates a singular, intense, dense sound that eliminates space and focuses the listener’s attention on the immediate “sound” of the music rather than the music as a sphere of intertwining elements – it precludes the need or stimulus for anticipation or prediction of resolutions and centers the mind on a feeling of “now”, it perceives composition as a singular unanimous roar rather than a dialogue between different elements or interlinking sets of perspectives. It has a linear impetus, where one is in thrall to the tyranny of the guitarist’s will, as the guitarist is the sole author of compositional narrative, not a panoramic impetus which recognizes the need to resolve melodic considerations collaboratively as different melodies are in play (this almost sounds like a political metaphor!). You quite rightly identified Sabbath and The Stooges as the first bands to make this a feature of their sound, thereby pioneering the template for all metal/punk music. One possible reason why this happened was by the late 60s lots of failed or wannabe guitarists were taking up bass and hadn’t studied bass in a formal sense so were unfamiliar with music theory and counterpoint and just played what they would have on guitar – thus rock ‘n’ roll became rock became later metal/punk. (Van Morrison made this point when asked what separated rock ‘n’ roll of the 50s/60s from rock of the 70s, i.e. bass playing became the work of people who never wanted to play bass in the first place so they treated it like second guitar.) Another (complementary) reason was that by the late 60s distortion pedals meant the guitar sound was so full it was overpowering enough on its own not to need to be just one piece of a larger puzzle, i.e. Jimi Hendrix. Filling out the guitar sound with bass rather than adding to it compositionally became sufficient. So to conclude, once the backbeat, that roving call-and-response bassline, is removed, you have metal and punk. Simple as that. But I don’t see how you can say this is not an offshoot of rock music. All the pioneers came from a rock/blues background (Iommi was a blues guitarist, Iggy Pop was a blues drummer) and the compositional technique featured intermittently in 60s rock bands (Beatles, Kinks, Sonics, velvet Underground, Cream, Blue Cheer, Vanilla Fudge) so it was definitely spawned by rock music even though it expanded upon the technique significantly. Or to put it another way, if rock music never existed then metal would never have existed.

interesting point about the nature of rock and its focus on creating a harmonic space where instruments doodle about, though “counterpoint” (which really means polyphony in the context of rock/metal, as true counterpoint has specific rules regarding the interactions of the various voices) would eventually be employed in a not-insignifcant number of metal bands later on (Iron Maiden, Morbid Angel, the melodic Swedish/Finnish bands). It was usually not employed incessantly, rather it was used at key junctures in a song further develop its artistic thrust.

Also, regarding metal’s relationship to rock, it wasn’t until death metal that metal fully divorced itself from rock. “plain” heavy metal — as played by Iron Maiden, Judas Priest, and yes, Black Sabbath — is really a subgenre of rock IMO. Not to say heavy metal is bad; the best of that genre stand alongside the best of black/death.

Metal is not rock. It uses the same instruments as rock, but so can jazz.

Proto metal is more similar to rock, but even heavy metal became entirely distinct from it eventually.

If metal is rock, then modern humans are neanderthals.

And baroque is renaissance.

Evasion of back back-based rhythmic patterns is definitely an important factor. Interesting quote by Van Morrison as well, seems to hold validity for many metal musicians/bassists (one example being Lemmy Kilmister).

Maybe I didn’t state it clear enough, but I do think metal sprung out of rock. However, like progressive rock it developed a very different compositional approach (among other things) to the extent that it should be regarded as a genre separate from rock. Indeed, alot of heavy metal is closer to rock though, so it is not an easy case.

I think everything you say here is true.

It is worth adding that there has always existed a regressive “rockifying” tendency within metal. Of course this phenomenon is not unique to metal, the same could be said about progressive rock, electronic music and punk as well. Neither is it particularly strange, rockist metal is often more popular among the crowd because it is easier to digest. That doesn’t mean that all rock-influenced metal is bad though, (some) heavy metal being one example, and or undergroundish stuff like Pyogenesis’ Ignis Creatio EP.

Really great article, one of the best I’ve read here. The use of “case studies” and the analysis of the music help to understand and support the arguments. There are two books that also posit that Black Sabbath are the creators of metal: “Black Sabbath and the Rise of Heavy Metal Music”, by Andrew L. Cope, and “Who Invented Heavy Metal?”, by Martin Popoff. Both are interesting. The first one analyzes some songs of Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin with the object of showing why the first group plays metal and the second one hard rock; the second book aims to show, based on comments of other musicians and of the author, why Black Sabbath can be considered the inventors of heavy metal and how the attempt to play louder created a context for the birth of the genre.

Another heavy rock song I think is interesting to listen to is “Happenings Ten Years Time Ago”, by the Yardbirds. I’m not a musician, so I can’t explain why, but I feel it has some similarities with “Sunshine of Your Love” regarding its relation to metal. And it’s a great song.

Thank you for the kind words. Andrew Cope’s book on Sabbath is a must for anyone who has an interest in metal music and/or music theory. Highly recommended but very expensive book. The Yardbirds are pretty neat, I can’t remember that particular song right now but I will check it out!

excellent article, always a pleasure to read Mr. Pettersson’s musings.

Great article! Thanks!

This would be nicer if it wasn’t so restricted to “household name” bands. Eg, some ‘heavy rock’ based on the same blues riff as “Sunshine of your Love”, but actually developing it over the course of the song,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fEX6VYfkHXI

Something somebody called ‘progressive’, but it’s actually pretty straight British psychedelic rock,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fq7W7eyvPbQ

This could also serve as good example of guitar and bass playing polyphonically. It’s also (unlike the Spooky Tooth) track not bound to a traditional song form anymore, with the vocals just being one of the instruments (and by far not the dominant one).

The idea that blues is somehow ‘sad’ is also bizarre — blues got standardized to death in the 1930 by professional song writers and professional players who were tapping into the market formed by the emerging black middle class and the ‘beautiful sadness’ (beloved by professional producers of unserious music as it’s the only emotion they’ve manged to fabricate assembly line style so far) didn’t arrive until much later.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qe74BtjMAsY

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=byZXD-AHg3g

This is just harmonically different without relating to established (European) functions of certain tone transitions.

Something to make the case for “metal is not rock” (and certainly not “rock on speed”),

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FL1pmhoTgaQ

Considering the enormous scope of the subject, I chose to do with more well-known names partly just because they are/were well-known. More obscure bands (some of them better than the stuff mentioned in the article) would of course be interesting as well, but perhaps better suited for a different kind of study.

I’m well aware of the fabricated nature of the blues as a musical genre. However, it is somewhat beyond the scope of this survey to go into the particularities and history of blues. That blues is “sad” is indeed a simplification, but the comparison still holds validity I think.

Critique is very much appreciated though, and I will keep your observations in mind in the future.

Great article. Are there some emotions (or ways of dealing with them) that hard rock and psych could not address effectively, and required the creation of the metal genre?

The romantic spirit conducive to transcending baser needs in favour of glorious struggle