What is developmental variation?

The term developmental variation was coined by Arnold Schoenberg as a name for the principle which governed his compositional technique, which he claimed to have inherited from the music of the great Germanic composers such as Haydn, Beethoven and, in particular, Brahms. The technique consists of generating development in a piece through variation of an initial idea. Each new slice of content is developed from, and naturally connected to, the previous one, so that the whole piece is an elaboration of an initial idea. This provides unity and logic within dramatic movement and variety.

Why developmental variation?

Since the end of black metal around 1996, underground metal has found itself in a rut. As if struck dumb by the dizzy heights achieved by its greatest practitioners, most underground metal bands have veered into three equally fruitless directions:

- Blatant imitation of a specific set of bands from the past (New wave of old school death metal, Thrash revival, Darkthrone clones, etc.)

- Commercialization of the aesthetic, achieved through simplification of lyrical themes and musical structure (In Flames, Dimmu Borgir, deathcore, etc.)

- Experimentation in texture and instrumentation, fusion genres (Norwegian avant-garde, Djent, etc.)

One would assume that the practitioners of this third path feel, at least, the anxiety that naturally comes with working beneath the shadows of giants. Their response, however, betrays that anxiety to an excessive degree, as they scramble madly to distance themselves from those past greats, usually through the most immediately striking means they can find. Often with releases of this variety one is left with the sensation that they could be truly great works of art if they stopped hovering uncomfortably around the ghost of metal, and simply embraced their external tendencies. In other words, the solution most of these artists seem to find to the problem posed by the intimidating canon is to escape metal altogether, as many of them ultimately do.

This is not, however, because of any inherent flaw in the style, or any linear finality implied by the greatness of the canon. There is no denying that, in a sense, underground metal is a restrictive style. There are strict boundaries regarding instrumentation, tonality, and even lyrical themes (that old Euronymous joke about carrots notwithstanding). Though these may at times be somewhat malleable, when they remain blatantly unobserved the music simply stops sounding like underground metal. It is largely the imposing presence of these boundaries that has scared many promising musicians away from metal, and into the realm of the often masturbatory and self-referential pseudo avant-garde.

What this ultimately means is not that there is no room for growth within heavy metal, but that said room is to be found in a less immediately evident, but ultimately more significant element of musical construction; structure. Underground metal’s unpitched vocals allow it freedom from many structural conventions of popular music in which vocals are the lead instrument. Its literary and historical inclinations give it plenty of places from which to draw extra-musical influences. Heavy metal titans Iron Maiden have successfully done this in the past, shaping their more structurally ambitious and musically exciting pieces around the contours of literary or historical subjects.

The aforementioned underground metal greats have already exploited these natural tendencies. Albums such as Altars of Madness and Far Away From the Sun have expanded rock’s traditional strophic structures through the use of expansive melodies and conflicting themes, creating instrumental sections of great intensity, which modify the meaning and intention of the strophic recurrences. Greater variety in the stricter tenets of instrumentation and mood has been justified within the framework of a modified structural thought-process, for example in the Burzum albums Det som engang var and Hvis lyset tar oss. There are countless other examples of individual structural voices developed by bands in order to best fit their particular path or concept, from the intensely concentrated minimalism of Beherit and Skepticism to the outwardly chaotic narrative intricacy of Demilich and early At The Gates.

However, this was underground metal at its youthful best, when it was still discovering what it was and what it could do, and many of its greatest achievements were at least partially the product of amateurish accident. Metal is no longer a young musical style, and perhaps in order to age gracefully bands will need to sacrifice some spontaneity and be more strict about inwardly articulating their goals, the structure that will best fit these goals and the compositional process that will get them there.

Underground metal is a genre with entirely unique thematic concerns, which prizes the ability to create works of musical individuality that are still ultimately works of underground metal. Developmental variation is the perfect technique for this situation, as it allows content to organically generate form, which would not only allow for individual songs and albums to craft an individual perspective without resorting to surface gimmicks, but also lead to a deeper level of thematic coherence. In a style whose fans expect recordings to hold up on repeated listens, not for weeks or months but for years, the increased layered complexity of musical relationships created by this technique would heighten, not obscure, the expressive power of a particular song or album.

It is not enough for underground metal to simply lift structural arrangements from sources more sophisticated than rock and pop music, such as European classical music. Though this could work individual songs or albums planned around the idea, as it did for Fanisk on their debut Die and Become, it is not a suitable long-term direction. This is because at the end of the day, the practice is not too distant from the simple lifting of vocabulary from other sources, a practice whose short-lived capacity to produce quality content the underground has already witnessed.

However, there is a lot to be learned from the music of the Common Practice Period. There is a tendency to view classical forms as being set in stone, but this could not be further from the truth. The image of Beethoven stressing over whether or not theme B of his sonata form modulated to the bloody dominant or not is silly enough to dispel the notion. The truth is that these structures developed organically throughout the lives of many composers, growing around the type of thematic material and harmonic conventions of their time and style, until they became intuitively standardized elements of musical grammar. It is only much later, once their development had been completed, that theorists could attempt codifications.

Attempting to imitate such a process of could prove fruitful for underground metal bands. The idea would be for bands to create their own structural grammar, not by adhering to a new set of rules, or worse, an old one belonging to a different tradition, but by developing a new, more sophisticated intuition. It is this author’s belief that the technique of developmental variation could be extremely helpful towards this development. It will of course always be important to have a good idea first; no technique will write good music for you.

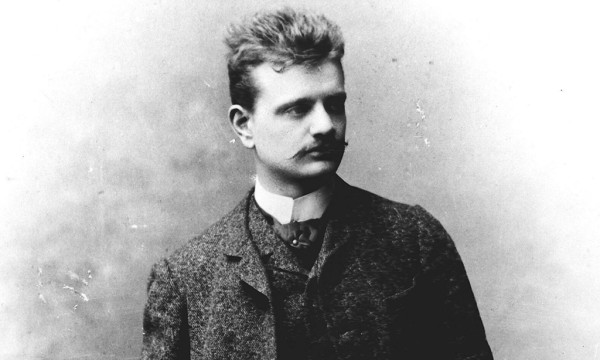

In the interest of getting all of this across to the reader’s musical instincts, as opposed to getting it across merely to his or her understanding, where it is useless, we will now undertake a case study of how this technique worked for the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius in his early tone poem, En saga. Sibelius faced a dilemma similar to that of the young Hessian today, standing in the shadow of a beautiful but intimidating tradition. By molding the structure of his piece around his material, through the technique of developmental variation, Sibelius managed to find a powerful individual voice for his piece, without resorting to gimmicks, or leaving the tradition he loved behind.

En saga: a case study in developmental variation

En saga is an orchestral tone poem, meaning that it is an entirely instrumental piece meant to describe or depict something outside of itself. The piece’s title translates simply to ‘a saga,’ and throughout his life Sibelius never specified whether it was based on any particular one. This clever bit of ambiguous programming presents Sibelius with a very malleable structural mold that nevertheless presents a general framework within which to work.

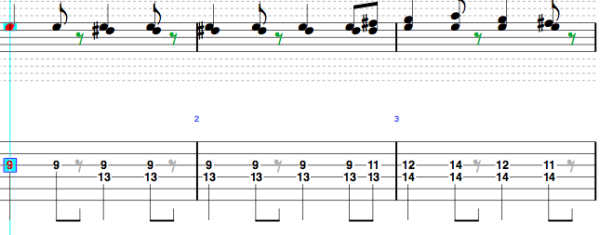

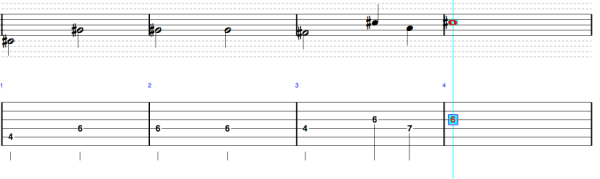

Sibelius builds nearly 20 minutes of music around four simple themes. All but the last of these has a length of four measures or less, and all of them keep the melodic action centered around a perfect fourth or fifth, emphasizing stepwise motion. The reader may have already noticed that this description could fit many metal riffs like a glove, and this proximity of thematic character to underground metal is one of the reasons why this piece is particularly relevant to our interests.

The relationship between themes I and III is evident: they have the same range and an identical ending, being distinguished from each other by slight rhythmic variation and harmonic context. Though theme II might initially seem out of place, its ‘justification’ comes with the introduction of theme IV, a majestic melody that combines rhythmic and melodic elements from themes II and I-III. It also emphasizes the motivic element that unites all four of them; the repeated insistence on the starting pitch. This characteristic in particular is the one that betrays the tight relationship between the themes, allowing us to comfortably refer to them as variations on the same idea. The imaginative reader will begin to see how the relationships and conflicts between these four simple themes begin to lay out sketches of a large-scale work, or, in other words, how developmental variation suggests not only material, but also structure.

The piece starts off with a short introduction that leads into the uncomfortable minor seconds of the first theme (0:17), establishing the tension that drives the whole work. The theme is then pitted against wave-like arpeggio figures in increasingly tense juxtapositions, which seem to be leading towards an explosive climax, but then simmer away into an uncomfortable silence. The way this opening minute mirrors the structure of the entire piece, like an eerie premonition, is an indicator of the piece’s impressive unity, and a perfect example of the way relationships between related themes can be the basis for entire compositions, an idea we will return to later.

I said that I admired its (the symphony) style and severity of form, and the profound logic that created an inner connection between all of the motives. — Sibelius, conversation with Gustav Mahler, Helsinki, 1907.

This silence is broken by the sudden introduction of theme II (1:08) by the bassoons, in a tonal center very distant from that with which the piece began. However, the reappearance of the insisting note motive makes its appearance seem like a natural response in a conversation. After the statement, the conflict of the piece is laid out for the listener and the piece unravels with absolute naturality. Theme II passes around the orchestra, competing with increasingly dissonant response passages until its motives flower into a wonderful heroic melody in the double basses. This initiates a dialogue in the string section that spells out the conflict between the two main theme groups with great clarity.

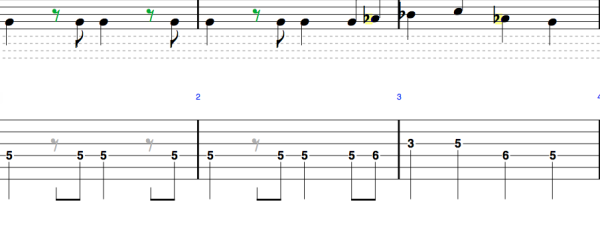

Sibelius then goes on to present themes III (in the violas at 4:09) and IV (in the strings at 5:07) in a similar way, declaiming them lyrically throughout the orchestra and pitting them against transitional passages, often arpeggiated. The seeming culmination to which the piece comes after the presentation of triumphant theme IV is suddenly interrupted by a short bridge passage (5:44), tellingly outlining a fifth, which leads into a section centered around permutations of theme III and a flowing legato response idea that begins to overpower the theme itself. Theme IV’s conquest remains unattained.

Then, suddenly, the momentum collapses and we are led into the second part of the piece. This second section consists of a series of crescendos, in which particular themes seem poised to triumph and reveal themselves as ‘the’ theme. Yet, time and again these crescendos collapse in on themselves, eerily, almost unnervingly. Until, at the very last of these peaks, a response figure once again takes over the climax. Yet the fanfare quickly dissipates, and the piece ends with an extremely quiet and nearly uncomfortable uncertainty.

This second section appears to be what the themes themselves initially suggested, thanks to their close “variation” relationship: a conflict in which one of them emerged triumphant. In order to get a more intuitive sense for the depth of this relationship and its importance, notice how after a few listens of the piece the themes will be stuck in your head almost interchangeably, to the point where it is sometimes hard to tell which one you’re humming to yourself. This is the sort of conflict that arises naturally when material is created through developmental variation, and it is what makes it such an effective technique for the composition for styles that thrive on dramatic tension.

Now, Sibelius’ choice to make none of the themes triumph and to end the piece the way he does is not something intrinsically suggested by the themes. As a matter of fact, if we are allowed a guess, this was probably the narrative idea that Sibelius started out with. However, once he had his material, he had a pretty good outline for a conflict, as themes I-III and theme II clearly converge and culminate on theme IV. However, as previously noted, the first triumphant statement of theme IV is quickly negated by the aforementioned bridge passage, a dissonant entry of the theme and then the shifting of focus back to theme III.

The series of increasingly chaotic and dramatic anti-climaxes that constitute the second portion of the piece are the ones that outline the thematic conflict proper, along with the ultimate failure of any of the themes to impose themselves, even as they alternate and hybridize. However, in order for this section to make any sense, especially given the piece’s light programmatic tinge, the opening section in which the themes are presented becomes absolutely necessary. In order to establish the tension that rules the piece and give it coherence, the strange introductory section dominated by theme I becomes necessary.

This introduction mirrors the development of the whole piece, with its agonizing rising and falling motions, which eventually dissipate into a tense silence. Sibelius found his large-scale structure through his themes, and then constructed every other sub-section around the same general curve. This creates an immersive fractal effect, potent evidence of Sibelius’ developing genius despite the orchestration failings and occasionally meandering quality of the still young composer. A dramatic idea and four simple, closely related, themes allowed Sibelius to reach heights of structural ambition that, though not yet fully realized, would become the germ for his future masterpieces.

Closing words

I am by no means suggesting, of course, that is ‘the’ path metal must follow in the future. This is a suggestion, and idea, and more so than it hopes to be accepted, or even fully understood, it hopes to ignite some spark of creativity. Metal does not necessarily need developmental variation in order to escape it relative stagnation, but it does need to look at itself more seriously and its surroundings more seriously, and ask itself musical questions in a more articulate manner. Hopefully this article will be of some help to that end.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VyDRWw_g2xU

11 CommentsTags: arrangement, composition, developmental variation, jean sibelius, motif, structure, theme