Way back in grade school, before you hit the age of sexual competition and thus get more rigorously socialized, one of the more exciting things to do is spend the night at a friend’s house. This means you get spoiled by well-meaning parents, can order pizza with all the toppings, and spend the night watching scary movies on the DVD player. At that time of life, it’s pretty cool, although once you’ve moved on to bigger things it seems like a parody of a really bad party. Who’s got the ranch dressing potato chips, indeed.

It’s conventional, among nice families, to keep this charade going until noon or later the following day, mainly because that’s about how long it takes the caffeinated soda pop and sugar foods to wear off, meaning that all parties are tuckered out and need to be taken home and shoved onto a sofa with homework “for your own good.” This is a kindness extended between families to each other, allowing your parents to actually have a night alone while you’re rampaging at some other kid’s house. Of course, if you spend Saturday night with a Christian family, or Friday night with a Jewish one, it means you’re going to some kind of exciting religious service in the morning.

Back in those less preference-enabled times, I’d go along to Church or Temple with my friends and wonder at the death denial of adults. There were great things about church – mainly the music, but I also liked the weird little tasteless wafers at communion – and Temple had its moments, mainly the times when they’d bring out the big old scroll of Hebrew writing and chant in languages I didn’t understand. In general, however, to young Spinoza Ray it seemed like adults getting together to agree on an excuse why we don’t actually die, and to answer at least two questions along these lines before saying something blithe like, “Fluffy is in heaven with God now, and can chase cars every day and is always happy.”

What I remember more than anything else was the expectation going into these religious services. There were the smells of adult clothing, perfumes, foods, alcohol and the flatulence and dyspeptic belches of the usual healthy specimens, mostly older, who cleave to churches like AIDS patients to retrovirals. But more than that, there was a subtle kind of excitement: it was an event, and there was an expectation, whether Jewish or Christian. You were going to a place of higher authority to receive wisdom, and it was to be a cathartic experience.

Recently, in my wandering through the smouldering ruins of the metal community, that being all people who create or appreciate the non-radio metal of our world, I was amused by how popular the term “cult” remains among those who are metal. We’re a pure metal cult! and Only metal is true! and I swear allegiance to metal! and other comedic statements of this sort are common, like a dinner opera about patriotism. These people are apparently oblivious to how disturbingly true their use of this term is.

A cult in my definition is any belief system that posits an Official Dogma and reinforces it, while sequestering all those who do not accept Official Dogma as outsiders. It’s a precursor to bureaucracy, and in the case of Christian cults, at least, it’s about like filling out a triplicate application. Do you believe in the father? (check) Son? (check) Holy Ghost? (check) Heaven and Hell mythos? (check) And are you willing at this time to sign an eternal contract to this effect?

In churches, people surge to the front of a large building while music plays and people in costumes perform ceremony to distract them (note for our alert readers: Judaism is much similar, but Christianity is a more familiar example for most North Americans, and since the two share most beliefs in common). There they take refuge in the comfortingly familiar nature of religion; you have been through this ceremony before, and you know what will happen, and at the end, your own expectation of receiving catharsis carries you through to that conclusion. Basically, it’s a lot like LSD: you find what you expected.

Rock concerts and metal concerts are very similar. You sanction the ceremony by paying money, thus you have reason to believe you are accepted unless you perform heresies, such as fistfights or too much covert marijuana smoking behind the fat guy standing up front. People in uniforms herd you into a place where people in costumes perfom onstage, playing music you have usually heard on CD. Even more, for those who are lost, every song no matter how convoluted at some point returns to the constant drumbeat, usually snare, which builds cadence and interrupts any thoughts you were having between beats, which are the loudest single element of the concert.

The metal cult, like the rock cult, is based in the idea of catharsis. You go to see some band you have heard before, and after having the music affirmed, you go away with some brilliant insight like “They really can play their instruments” or “That vocalist vomiting blood, fire, semen and feces was spectacular!” It’s not rocket science. If you’re a musician, you can feel ever-so-elite by watching the band members play and pulling from it some observation about how well the guitarist frets or drummer hits the middle of the goddamn snare twice every second. No one is left out; if you had $5 in your sweaty little hand when you went in the door, you were given the communion, allowed to join the cult, and ushered on out into the surprisingly cool and unsweaty night.

Baptised in beer, perhaps intoxicated yourself on a range of exciting substances, you even have a chance to double affirm your belief by buying tshirts and CDs, and can even talk to the band members, who periodically deliver such benedictions as, “This is another song about fucking the dead – I want to see you fuckers tear it up in the pit!” Conventional academics like Deena Weinstein periodically set aside the Chardonnay (all academics are drunks, drug addicts or perverts) and to observe what an indoctrination this ceremony is, and how it affirms membership in a group. She might as well say “…membership in a true life-hating metal cult!”

Surprisingly, black metal was a counterinsurgency opposed to this. Initially, bands like Burzum and Immortal eschewed live performance, since as they correctly observed, hordes of idiots would show up expecting everyone to accept them purely on the basis of having (a) found the venue (b) being aware of the band and (c) the benighted $5 in sweaty fist. Burzum’s composer was vehement about it, and to this day you can find credulous teens everywhere buying $20 live bootlegs of a band that never played live (but since it’s $20 and not $25, it’s a “good deal” – you get an extra $5 to go to another stimulating concert).

Much maligned, mocked and parodied, the “No mosh, no core, no fun, no trends” attitude of these early bands was a way of ending the religious service, an inclusive event, and turning instead to an esoteric event. The difference between exoteric religions like Christianity and esoteric religions like, say, Advaita Vedanta or Buddhism, is that in exoteric religions you have to show up and affirm Official Dogma, and then you get sent home with a stamp on your triplicate form, which esoteric religions are best summarized as “the truth reveals itself in varying degrees to those who seek it.”

Christianity and rock concerts are birds of a feather that give you a 100% guarantee that everything’s okay, and then convince you to turn off your mind so you can do something useful like enforce Official Doctrine on other people. They are the ultimate populist religions, and by that nature they must assert that everyone is equal because, lacking an entrance requirement, they’ve already made it fact. If you can make it to church, or find the rock club with your $5 (donations are always welcome at church, too), you’re one of the Chosen and can feel better than other people for your non-achievement.

One of the reasons I separated out Christianity from Judaism as an example, earlier, is that Judaism is controversial because it is simultaneously a religion, a culture, and an ethnicity. Whether Khazar or Ashkenazi, you’re a Jew if you have any of those three attributes (bonus points and free instant coffeemaker for all three). Among the black metal community, there are those who feel Judaism is the great downfall of Indo-Europeans, and they wish nothing of tolerance for it.

I’d like to take time here to praise some aspects of Judaism. Its emphasis on education, for example, is admirable, and far exceeds the Christian dogma that if one believes in God, it’s okay to fail at everything else in life because it doesn’t matter – what matters is the world after this one, which like a credit report, is absolute and binding and more important than whatever goes on here in our misery of animal existence. Its racism and cultural supremacy is beyond questioning, and has kept the Jewish people alive and functional through thousands of years of wandering through other peoples’ countries. In fact, until Christianity sedated Europe, Jews never had a homeland, and at this point are as European as they are Semitic/Mongoloid.

Christianity has selective praiseworthy aspects as well. As Arthur Schopenhauer pointed out, its only significant difference from Judaism is a classic Indo-European trait that can be found among the Aryan sages of ancient India, that being “quietus,” or an inner spiritual calm and contemplation to discover the blessings of this world. If you’re Arthur Schopenhauer, or Meister Eckhardt or Ralph Waldo Emerson, and thus possess not only a genius IQ but an introspective desire for truth and beauty, this will occur to you. The remaining 99.99% of Christians should simply admit they’re following non-ethnic Judaism, and cease feeling superior to Jews for having a martyr who gave his life because we’re dirty little animals who fornicate, murder, embugger and thieve from each other daily.

One reason I can’t ever be a neo-Nazi, besides my ethnic Scottish heritage which includes pre-Jewish Semitic Gaelic blood, is that they didn’t act on this crucial difference, in part because in Germany the Christians had already slaughtered anyone with a desire to resist Christ a thousand years before. In my mind, Jews are an invading culture and I have no problem drawing a sword against them, men women and children alike, to drive them back into the middle east, where they may have to actually stop feeling superior to their Abrahamic brethren and make peace with the Arabs. Not my problem. But, I feel the same way about Christianity: if you’re not Eckhardt, or Schopenhauer or Emerson, I recognize that it’s my duty to draw a sword against you, man or woman or child or dog or AI, and drive you out of Indo-European lands before you destroy what’s left of our culture.

However, I’ve come to realize that “No mosh, no core, no fun, no trends” is also part of this same militant desire which will come to any sane Indo-European who undertakes quietus long enough; rock music and metal are the same cult as Christianity and before it, sickly Judaism and its wheedling, whining culture of the lowest common denominator enshrined as benevolent love. For me, to love a culture is to defend it against its enemies, with emotional detachment and not the “hate” to which modern neo-Nazis masturbate in American History X-inspired fantasies. If you thought “the Holocaust” was bad, wait until you see what will come – and it is inevitable – when the current culture collapses and warlike people like me clear out bad Indo-European DNA, including Christ-worshippers and people whose sole contribution is to be “members of” some rock-music-based “cult.” Man, woman, child, and of course fat record producer scheming over cocaine and harlots in the back room, shall all face the sword – without hate, but without mercy, either.

With this revelation in mind, I have to ask modern metalheads who claim to hate stupidity and Christianity (and, of course, you cuddly stuffed NSBMer teddybears in your genuine NSBM tshirts and Nazi fetishist wear), why are you partaking in the same culture that you abhor? There are people among the rockers who are of noble countenance, and among Christians too, and I’d welcome these people into any future Indo-European society (Jews are ethnically excluded, along will all other non-Europeans; you have your own countries, go there and preach about your ideals and we’ll see how “superior” they indeed are). But for the most part, rock and roll is a failure at escaping Christianity. If anything, it’s a new form of Christianity that is even more accepting and less informative on the esoteric issues of spirituality, philosophy and comportment.

For this reason, both metalheads and neo-Nazis are ignored by their more studied peers. After all, who wants to get dragged into the same quagmire that has afflicted Indo-Europeans for the past millennia, albeit in a new form and with new products to buy? Advice to future rockers, metalheads, and the like: design your music and your career around something other than the glorified church service that is your modern metal “cult” concert.

1 Comment But how does the qualitative work in a society? After all, say the “wise” pundits, wouldn’t it be hard to organize a society around qualitative value, since only a few can assess it? This column offers an example in the small. Peer-to-peer file sharing can take many forms, but one of the most common is that of a hub; this is a small community where people exchange files. Normally, to get on a hub, you must have some quantity of files to be shared, and without that, you can be excluded “fairly” because, of course, everyone can see that you need to have a minimum amount of stuff to get on. Like cheap steak, it might be stuff that would only appeal to morons, but it shows you’ve done the effort and therefore deserve to be on the hub – that’s “fair,” sensu liberal democracy.

But how does the qualitative work in a society? After all, say the “wise” pundits, wouldn’t it be hard to organize a society around qualitative value, since only a few can assess it? This column offers an example in the small. Peer-to-peer file sharing can take many forms, but one of the most common is that of a hub; this is a small community where people exchange files. Normally, to get on a hub, you must have some quantity of files to be shared, and without that, you can be excluded “fairly” because, of course, everyone can see that you need to have a minimum amount of stuff to get on. Like cheap steak, it might be stuff that would only appeal to morons, but it shows you’ve done the effort and therefore deserve to be on the hub – that’s “fair,” sensu liberal democracy.

For the first video review to ever grace these pages a film was chosen that is valuable for the conclusions gleaned from its perception, and not necessarily the art of moviemaking exhibited. Following the pattern of most first films, this work starts with a group of characters and mocks them in their ouroboric paths to nowhere. In doing so, it reveals something of the nature of the metal community itself, both through its dominant symbols – drugs, masturbation, anger, fatalism – and through its own fascination and the conclusion it is able to draw. Shot in conveniently sparse videocam, the movie romps through a series of goofy but enjoyable skits and long derangements of the senses synchronized in form to music, giving it the feeling of a music video + home video + low-budget film in one. Of note are musical choices, which showcase a DJ’s eye for context. There is ample T&A of a tame variety and gratifying indulgence in all forms of base humor, including masturbation, fecalism and amusing violence. Highlights include a series of blown-out female characters who are preachy but have the sexual ethics of a Grimoire Girl(tm), a fantastically fascist cop played by Craig Pillard, and several utterly believable stoner/metalhead characters who wander around in a haze of mostly their own creation. Absent is any moralism regarding the world around us; it is nice to escape that moralistic confine in which most contemporary filmic art is launched. Another highlight is “Ox,” who barges his way onto the set and provides one of the most believable character satires of pure rampaging destruction in human form yet found. Toward the beginning and end of the film, when it needs extra impetus, there is booster rocket material from what are now basic digital editing effects, which to the director’s credit are often quite cleverly applied (“making the most of what you have”). Is the movie “good”? No and yes. It’s hard to sit through some of this; the scenes are long and often tediously embarrassing to the degree that sympathy is lost for the characters and even the joke. As a whole, the plot is light, with three or four major devices and a linear narrative based on its precepts. It’s sometimes difficult to watch from a combination of ineptitude and padding. However, it is “good” in that this movie has a large amount of perceptive content for a cut-up laugh fest, and while its methods and often gags are cheap and sometimes predictable, they’re carried out with a unique flair and nurture for the humor involved. Like any modern comedy, the plot is a container for almost granularized skits woven roughly into the context of the people who drive changes in the action, and this approach works for the scattershot method required to address the diverse complexity of intellectual representation of external reality in this era. The acting isn’t great, but Zebub himself is a high-energy riot of comedic momentum who can be witty in a pinch, or subtly humorous over the length of a scene. His supporting cast perform well compared to many card-carrying actors and, while like in the movie itself we can see rough edges there are imperfections galore, they link up in the film like prisoner sex. While this movie gets a somewhat ambivalent recommendation, the idea of pursuing the next professional offering from Bill Zebub is not at all ambiguous to this reviewer.

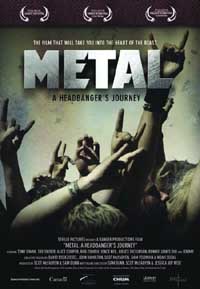

For the first video review to ever grace these pages a film was chosen that is valuable for the conclusions gleaned from its perception, and not necessarily the art of moviemaking exhibited. Following the pattern of most first films, this work starts with a group of characters and mocks them in their ouroboric paths to nowhere. In doing so, it reveals something of the nature of the metal community itself, both through its dominant symbols – drugs, masturbation, anger, fatalism – and through its own fascination and the conclusion it is able to draw. Shot in conveniently sparse videocam, the movie romps through a series of goofy but enjoyable skits and long derangements of the senses synchronized in form to music, giving it the feeling of a music video + home video + low-budget film in one. Of note are musical choices, which showcase a DJ’s eye for context. There is ample T&A of a tame variety and gratifying indulgence in all forms of base humor, including masturbation, fecalism and amusing violence. Highlights include a series of blown-out female characters who are preachy but have the sexual ethics of a Grimoire Girl(tm), a fantastically fascist cop played by Craig Pillard, and several utterly believable stoner/metalhead characters who wander around in a haze of mostly their own creation. Absent is any moralism regarding the world around us; it is nice to escape that moralistic confine in which most contemporary filmic art is launched. Another highlight is “Ox,” who barges his way onto the set and provides one of the most believable character satires of pure rampaging destruction in human form yet found. Toward the beginning and end of the film, when it needs extra impetus, there is booster rocket material from what are now basic digital editing effects, which to the director’s credit are often quite cleverly applied (“making the most of what you have”). Is the movie “good”? No and yes. It’s hard to sit through some of this; the scenes are long and often tediously embarrassing to the degree that sympathy is lost for the characters and even the joke. As a whole, the plot is light, with three or four major devices and a linear narrative based on its precepts. It’s sometimes difficult to watch from a combination of ineptitude and padding. However, it is “good” in that this movie has a large amount of perceptive content for a cut-up laugh fest, and while its methods and often gags are cheap and sometimes predictable, they’re carried out with a unique flair and nurture for the humor involved. Like any modern comedy, the plot is a container for almost granularized skits woven roughly into the context of the people who drive changes in the action, and this approach works for the scattershot method required to address the diverse complexity of intellectual representation of external reality in this era. The acting isn’t great, but Zebub himself is a high-energy riot of comedic momentum who can be witty in a pinch, or subtly humorous over the length of a scene. His supporting cast perform well compared to many card-carrying actors and, while like in the movie itself we can see rough edges there are imperfections galore, they link up in the film like prisoner sex. While this movie gets a somewhat ambivalent recommendation, the idea of pursuing the next professional offering from Bill Zebub is not at all ambiguous to this reviewer. I just saw this at the Alamo Drafthouse, and I was surprised at how much I enjoyed it. It is probably the most watchable movie on the topic thus far, as it actually has a budget and properly addresses the many subgenres. It stays focused on the more populist bands (Wacken is a prominent setting) but I find that getting into all the underground minutiae bottoms out these days because whether people are motivated by commerce or popularity, the effect on the music is just as deletrious. Sam Dunn, the filmmaker, is a contemporary of the 1980s metal (30-ish, grew up on thrash and death metal, cites Autopsy as one of his favorite bands) so it is worth supporting and good fun. The interview with Gaahl and then Dio repeatedly ripping on Gene Simmons are worth the price of admission.

I just saw this at the Alamo Drafthouse, and I was surprised at how much I enjoyed it. It is probably the most watchable movie on the topic thus far, as it actually has a budget and properly addresses the many subgenres. It stays focused on the more populist bands (Wacken is a prominent setting) but I find that getting into all the underground minutiae bottoms out these days because whether people are motivated by commerce or popularity, the effect on the music is just as deletrious. Sam Dunn, the filmmaker, is a contemporary of the 1980s metal (30-ish, grew up on thrash and death metal, cites Autopsy as one of his favorite bands) so it is worth supporting and good fun. The interview with Gaahl and then Dio repeatedly ripping on Gene Simmons are worth the price of admission. What is excellent about this documentary is its bonehead simplicity in tracing the history of metal. It focuses on nodal points where single events touched off nascent convergences and caused paradigm shifts. Not all of these are musical events; much of the footage is devoted to showing how changes in history prompted changes in metal. This attitude allows it to peer into the motivation behind metal musicians more than any other documentary extant. The strength of this documentary is its star power in pulling in all of the classic figures in heavy metal for interviews. The big names show up, and get put at ease and asked questions by people whose journalistic intent matches a fascination with rock music as an event. When their answers are put in context, the result is metal history like a scrolling tapestry passing our eyes. The centerpiece of this documentary are the glam years of Hollywood bands from Van Halen to Guns and Roses, and much of it is intended to make them look more sophisticated and intense than their European counterparts who invented the genre. Speed metal gets an offhand mention, and underground metal gets entirely skipped. Its focus is not surprisingly on the kind of metal that makes it to the VH1 video channel and makes pots of money. In its coverage of glam rock, power ballads, bad boy rebels and drug abuse this film is most lucid. Humorously, the glam rockers, twenty years later, look somewhat diseased, while Tommy Lee still looks vile and combat-ready. Even funnier: of all the people interviewed, a remarkably self-confident and unpretentious Sebastian Bach is the most articulate and uncomplicated. Unfortunately, other parts of the film portray metalheads as wounded, out-of-control children who make this horrible, violent music because they’re defective. While these flaws weaken the documentary, and disable it more in post-viewing analysis when the viewer realizes the documentary’s weaknesses stem from a desire to productize one of the last un-zombie’d genres, “Heavy: The Story of Metal” has many positive factors, not least of all the simplest: the people who made it clearly enjoy metal music and wanted to portray it in a positive light, even if their definition of positive was twisted by their pocketbooks.

What is excellent about this documentary is its bonehead simplicity in tracing the history of metal. It focuses on nodal points where single events touched off nascent convergences and caused paradigm shifts. Not all of these are musical events; much of the footage is devoted to showing how changes in history prompted changes in metal. This attitude allows it to peer into the motivation behind metal musicians more than any other documentary extant. The strength of this documentary is its star power in pulling in all of the classic figures in heavy metal for interviews. The big names show up, and get put at ease and asked questions by people whose journalistic intent matches a fascination with rock music as an event. When their answers are put in context, the result is metal history like a scrolling tapestry passing our eyes. The centerpiece of this documentary are the glam years of Hollywood bands from Van Halen to Guns and Roses, and much of it is intended to make them look more sophisticated and intense than their European counterparts who invented the genre. Speed metal gets an offhand mention, and underground metal gets entirely skipped. Its focus is not surprisingly on the kind of metal that makes it to the VH1 video channel and makes pots of money. In its coverage of glam rock, power ballads, bad boy rebels and drug abuse this film is most lucid. Humorously, the glam rockers, twenty years later, look somewhat diseased, while Tommy Lee still looks vile and combat-ready. Even funnier: of all the people interviewed, a remarkably self-confident and unpretentious Sebastian Bach is the most articulate and uncomplicated. Unfortunately, other parts of the film portray metalheads as wounded, out-of-control children who make this horrible, violent music because they’re defective. While these flaws weaken the documentary, and disable it more in post-viewing analysis when the viewer realizes the documentary’s weaknesses stem from a desire to productize one of the last un-zombie’d genres, “Heavy: The Story of Metal” has many positive factors, not least of all the simplest: the people who made it clearly enjoy metal music and wanted to portray it in a positive light, even if their definition of positive was twisted by their pocketbooks. Aimed at the most popular examples of heavy metal, this analysis peers into issues of gender and power as ethnographic vectors of impetus toward participation in the metal genre. The interpretations of reasoning and ideologies behind music, while limited to less than self-articulate examples in many cases, are the strength of this book.

Aimed at the most popular examples of heavy metal, this analysis peers into issues of gender and power as ethnographic vectors of impetus toward participation in the metal genre. The interpretations of reasoning and ideologies behind music, while limited to less than self-articulate examples in many cases, are the strength of this book.

A broadly inclusive view at the public perception of heavy metal and its fans which, although limited to mainstream music, captures the unstable origins of modern metal, this book provides a solid foundation for Weinstein’s comments on metal.

A broadly inclusive view at the public perception of heavy metal and its fans which, although limited to mainstream music, captures the unstable origins of modern metal, this book provides a solid foundation for Weinstein’s comments on metal.