Heavy metal was born in very late 60s and early 70s as a merger of heavy rock, proto-punk, horror film scores and progressive rock, carving out a new form of dark music that spelled out longer phrases than rock by using moveable power chords in complex riffs.

Metal outlasted its influences. While punk would rebirth itself as hardcore punk and go on to exert an enormous influence on later developments in metal, progressive rock was more or less depleted as a creative movement by 1974. However, during its relatively short “golden era” during 1969-1974, progressive rock generated a substantial and groundbreaking corpus of music whose legacy lives in other forms of music to this day, and which is well-worth discovering for its intrinsic artistic value.

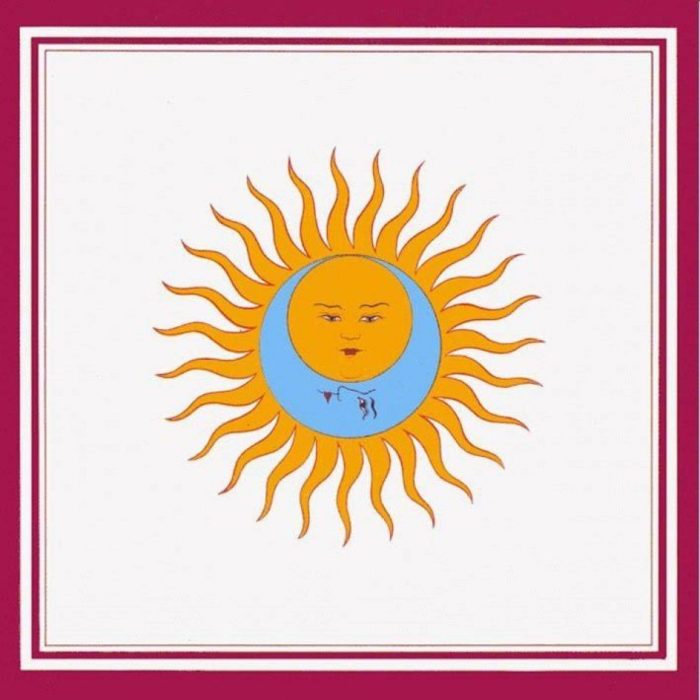

King Crimson helped define progressive rock in the late 1960s and early 70s, contemporaneously with the first metal albums from Black Sabbath, and produced the most profound impact on not just heavy metal but underground metal, which was partially inspired by its intricate song structures. Not only did the group define one thread of progressive rock with their iconic debut album In the Court of the Crimson King, they more or less provided what could be considered as an informal closure of the genre in its original form with Red (1974).

Metalheads have been inspired by Red for decades, in part because it is the Crimson release which bears the closest similarity to metal music with its riff-based, epic song material and decidedly metallic sound. Their 1973 album Lark’s Tongues in Aspic, while not as thoroughly “heavy” as Red, album embodies what could well be the noblest legacy of progressive rock, which also happens to be a long-standing feature among the pinnacles of the metal canon: the narrative approach to musical composition.

Musical narrative, a form of through-composition, occurs when each section of a song connects in a logical and meaningful fashion to the next so that the song as a whole forms an interrelated whole that qualitatively exceeds the sum of its individual parts, giving it a greater “poetry” or internal contrast between beginning and conclusion. A musical narrative does not necessarily involve the explicit telling of a story, but instead could be likened to going on a journey, embarking on a quest, or even experiencing a dream.

Musicologists generally refer to this merely as through-composition, or an internal dialogue between phrases without strict cyclic repetition, but the artistic dimension consists of this sense of journey or discovery, such that whatever is repeated occurs in a different context and by the end of the song, the receptive listener finds himself having reached conclusions different from what he perceived at the start of the song.

When discussing the principal characteristics of progressive rock, much attention tends to be directed at quantitative factors such as the lengths or complexity of the compositions without regard for what is actually happening in the music. Although progressive rock songs are longer than most rock works, that observation partly obscures features that are more related to qualitative data — such as the above-mentioned employment of narrative composition — which distinguish progressive rock from rock music at large.

An ordinary rock song could easily be extended to enormous time-proportions by applying more repetition and adding transitions like solos, but this would not create a musical narrative as represented by the original progressive rock bands in the early 1970s. This approach of elongation was (and continues to be) misused by musicians who apparently did not understand the point of the extended song format or lacked the skill or imagination do something meaningful with it. Almost every band that dabbles within the progressive genre has at least once attempted to write a lengthy piece, but very few have actually succeeded in creating compositions beyond ten minutes that maintain a coherent and meaningful musical narrative.

Classic progressive groups like Genesis, King Crimson and Yes succeeded in the construction of coherent and engaging songs that sometimes stretched past the twenty minute mark because they adapted form to content and not vice-versa, meaning that the structure of the song was dictated by the emotional and artistic content of the song, the “journey” if you will. Of course similar approaches can be found in other forms of music as well such as the Dealing With It LP by D.R.I., but progressive rock took great pains in writing songs that upheld this modus operandi over the course of the genre. This gave them the opportunity to compose music that both had time to breathe and traverse several layers of horizontal and vertical complexity before arriving at its final destination.

Context

Following the massive success of their 1969 debut album which effectively kick-started the progressive genre, King Crimson went on to produce a series of interesting but somewhat uneven albums featuring a revolving set of musicians. Perhaps a reflection of the fluctuating nature of the band at this stage, these records contain music of absolute splendor but do not really come together as unified wholes. Eventually internal frictions would start to take their toll on the involved parties, and King Crimson more or less imploded after the release Islands (1972).

Featuring a completely new line-up in addition to guitarist and permanent band-leader Robert Fripp, Lark’s Tongues in Aspic marked the beginning of a new chapter in the Crimson saga: a singular convergence of form and content. This incarnation of King Crimson is well-known for the virtuosic qualities of the individual musicians. However, the real strength of the ensemble lies in their collective musicality and almost telepathic ability for real-time composition. Allegedly, many of the songs on the album took form through group-improvisations, sometimes conducted in a live-setting, around preconceived motifs as well as semi-fixed themes and structures. Through this trial-and-error procedure they cultivated a fluid and organic approach to sound, style and songwriting.

Whereas earlier albums went for a “big” sound, Lark’s Tongues in Aspic is more about tight ensemble-interplay in the vein of a classical chamber orchestra. The jazz-tinged brass and wood-wind instrumentation heard on previous albums has been substituted with the voice of a sole violin. As a consequence, there was suddenly more room for all members of the band to be heard, a decision in line with the “chamber-rock”-orientation. For example, Robert Fripp could expand his presence in the music without being drowned out by the brass section. His angular lines and generally idiosyncratic way of treating the guitar would henceforth be recognized as a trademark of the band.

Traces of older King Crimson — adaptable song structures, thematic development, counterpoint, improvisation, power chord-based riffs and an eclectic musical repertoire with references to classical, jazz, heavy rock/metal and folk music — are present, but have been channeled into a more integrated form and expression. This enabled the band to work with a wide musical and emotional palette without sacrificing internal coherency or losing direction. A subtle, almost esoteric sense of balance, unity and meaning in the midst of struggle, chaos and confusion permeates the album as a whole.

By thriving on the tension generated between seemingly diametrical concepts (darkness/light, force/delicacy, formal intricacy/spontaneity, clinical precision/playfulness, etc) the band was able to create music of great subtlety and dynamics. The raw material is then poured into unconventional but not arbitrary song-structures; everything that happens in the music relates to the ongoing musical narrative.

Analysis

Lark’s Tongues in Aspic consists of six tracks, divided into equal parts instrumental compositions and songs. The two instrumental title-tracks which bookend the album form a continuous musical narrative despite the fact that they are divided by the album’s song-based middle section.

What follows below is an attempt to map out the overall structure and content of “Lark’s Tongues in Aspic, Part One” and “Lark’s Tongues in Aspic, Part Two” in order to throw some light on King Crimson’s methods for constructing narrative-driven progressive rock. The reader will notice that a larger amount of space has been devoted to the first part of the title-track in comparison to the second part. This has partly to do with the structural differences between the two compositions; the linear, multi-sectional nature of Part One is better suited for a conventional musical synopsis than the tight, cyclical structures Part Two. But it also addresses the fact that Part One contains most of the motivic and thematic material used in Part Two as well, although in modified form.

“Lark’s Tongues in Aspic, Part One”

Starting off the album and clocking in at 13:36, “Lark’s Tongues in Aspic, Part One” is a richly textured and thoroughly dynamic multi-sectional group-composition that takes the listener on a startling journey encompassing a broad range of emotions and moods.

Section I:

“Lark’s Tongues in Aspic, Part One” begins with a relatively long introductory section that aids the listener in getting into a proper headspace. Lightly tinkled, tuned percussion comes in first, followed by a substantial arsenal of additional percussive instruments and metallic sounds. A subtle use of tape-loops featuring violin can be heard as well. Sonic density is increased until the listener is fully absorbed in a microcosm of bells and metals. After peaking, the swarming percussion embarks on a journey back into silence.

Section II:

The “neutral” and meditative atmosphere of the opening section gives away as the violin makes its entrance. A strained, slightly nervous “riff” performed staccato on the violin establishes a firm 10/8 meter (or 5/4, if you wish) proportioned into 3-3-2-2 eighth notes. This is a crucial event, since it introduces the first of two main motifs upon which a good deal of both parts of “Lark’s Tongue in Aspic” are built. It’s a purely rhythmic motif consisting of the above mentioned metric figure. The motif is also employed in modified forms depending on the established meter of the part in question (i.e. 3-3-2 in 4/4, and so on).

The violin-line gradually ascends its dyads in chromatic steps while keeping the lower of the two tones (C) as a point of reference. Meanwhile, the electric guitar introduces a contrapuntal voice moving in the opposite direction from C downwards. This maneuver magnifies the sense of uncertainty and strain already established by the violin, and it grows ever so urgent as the underlying harmony begins to dissolve.

Release comes in the form of a vigilant outbreak by the drums, and then the roof comes crashing down as an earth-shaking heavy metal-riff played in power chords on the guitar sweeps away everything in its proximity. Despite the harmonically liberating effect of the riff, it’s far from triumphal in character. The guitar figure highlights a tritonal interval (starting on the tonic G and ascending to Db) causing the riff to sound both powerful and destructive — a common feature in the music of King Crimson and, of course, metal music in general. Meter is temporarily adjusted to 7/4 to cater to the form of the riff, and an explosion in sound amplitude is used to great effect here.

What follows next is a repetition of the two riffs, but with modified surroundings. For example, the guitar is joined by a delightfully fuzzed-out bass guitar which, like the guitar, strives against the motion of the violin. By changing the context of the riffs the band is able to keep things on edge, even though the re-entry of the metal-chords doesn’t have the same effect as it had the first time they appeared. All in all, the band never — or at least very seldom — resort to literal repetition throughout the composition.

Section III:

The common practice in 1970s progressive rock would be to juxtapose the previous metallic onslaught with a calm and preferably acoustic section. That is not the case here, though. Instead the listener is led directly into the dense and complex maze of trials which constitutes the track’s middle section. Inter-sectional transition between II and III is achieved by way of a short solo-inflection by the guitar, which also heralds the introduction of the second main motif: a three-note “melodic” succession of a rising fifth followed by a tritone, here spelled out as G-D-Ab. It may seem like the smallest of things, but the combined expressive qualities of these intervals are very well suited to the music at hand, and are effectively recycled by way of variation throughout both parts of the title track.

The lion’s share of Section III is constructed around the melodic and rhythmic implications of the two main motifs. Guitar, bass and drums engage in intricate contrapuntal interplay, utilizing — among other things — additive/subtractive rhythms and polymetric layering. Instrumental voices constantly diverge, catch up and re-unite as if to emulate an arduous trial. It all builds up to what seems to be a final conflict when the guitar shoots up in a burst of ear-piercing tremolo that outlines the intervals of the melodic motif. A truce-like resolution is inaugurated just as the music comes close to the breaking-point, offering a welcome respite. The battle is over, at least for the time being.

Section IV:

Out of the remains rises a lonely violin, backed up by the guitar playing variations on the main melodic motif, which contemplates the aftermath of the preceding section. Eventually the guitar fades away and leaves room for the violin to stretch out, first in liaison with a harp-like instrument and then on its own. The mood grows lighter while the violin dances away on a beautiful, far-eastern sounding scale. However, the immersive serenity stays marred by a premonition of impending doom.

Section V:

The vague sense of precariousness is replaced by acute realization when the guitar claws its way back into the sonic panorama and picks up the violin’s double-stop sequence from Section II. A chattering of human voices is heard somewhere in the distance, sounding like malicious whispers from a half-forgotten dream. Meanwhile, the violin joins in with a second melody to further reinforce the ascending anacrusis. A pattering of snare-drum tricks the listener into expecting a bombastic reappearance of the power chord 7/4-riff from Section II.

The band eventually returns to the riff’s G minor tonality, but instead of recapitulating the second half of Section II as one would expect the musical narrative takes a different, more sinister turn. Bassist John Wetton comes to fore and lays down one of the most sublimely haunting melodies in progressive rock history. In a dazzling display of portamento technique, the bass perfectly mimics a lamenting voice by hovering between tones. A black hole opens up to engulf the last streams of hope, leaving nothing but a tinkling of bells to bid the listener farewell as the music fades into obscurity.

“Lark’s Tongues in Aspic, Part Two”

The second part of the titular track is a fierce, riff-based piece of metal-influenced progressive rock written by guitarist Robert Fripp. It can be seen as a continuation of, or reaction against the events of Part One. By picking up motifs and reforging them into the context of a riff-centered heavy metal composition, the band is able to construct a confrontational composition whose main narrative purpose is to reverse the tragic outcome of Part One.

Whereas the multi-sectional Part One developed in a linear fashion, Part Two evolves through cyclic patterns with increased levels of intensity. The overarching structure can be described as three consecutive main cycles, each containing epicycles or minor cycles built from sequential repetitions and variations of thematic materials. It is possible to discern at least four main themes used in the composition, all of them readily discernible as being derived from motifs found in Lark’s Part One. Each theme appears in different forms (they are constantly modified both melodically and rhythmically), but can be roughly outlined as follows:

Theme 1: Chordal guitar-riff consisting of piled-up perfect fourths portioned into the 3-3-2-2 rhythmic motif presented in Lark’s Part One. Subsequent repetitions of the riff ascends by major thirds. Interestingly, it sounds distinctly metal despite its lack of power chords.

Theme 2: Angular and ominous riff (played in unison by guitar, bass and violin) derived from the main melodic motif of Lark’s Part One.

Theme 3: Ascending violin-line moving upwards via minor thirds. Vaguely resembles the violin- and guitar-figures from Section II and the beginning of Section V in Lark’s Part One.

Theme 4: Oppressive, power chord-based ostinato for guitar featuring a modified version of the rhythmic motif (3-3-2 in quadruple meter).

These themes define the mood of the composition and stand in dialectical relationship to one another. One could say that the themes act out against each other in a battle for prominence, and that their subsequent interactions trigger changes in the musical climate. For example, the ascendant qualities of themes 1 and 3 form a front against the adversarial and oppressive nature of themes 2 and 4. Perhaps this is better explained in narrative or literary terms: the ascendant themes represents the struggle of a protagonist against seemingly insurmountable obstacles embodied in the form of the two “counter themes.” It is a heroic contest which, in contrast to the dour outcome of Lark’s Part One, ends in victory as the antagonistic forces are finally subsumed and crushed.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vy3UiXb2uDQ

Conclusion

On the surface, “Lark’s Tongues in Aspic” Part One and Two may seem like very different entities. For example, the thoroughly aggressive and heavy metalized prog-rock that constitutes Part Two sounds relatively straightforward compared to the kaleidoscopic sonic/emotional landscapes of Part One (which wouldn’t sound totally out of place if scored for a classical chamber ensemble). However, a closer look at the musical content reveals that both songs use a similar set of motifs and themes which glues them together into a unified whole. When juxtaposed against each other they form a consistent musical narrative dealing with perennial topics such as struggle, loss and hope.

The fact that the two compositions differ in terms of structure lends further proof to King Crimson’s ability to let content dictate form. The band succeeds with the daring task of stepping outside of conventional rock-formulas without resorting to the tiresome adaption of formalized classical structures as is too often the case with lesser ambitious prog-rock bands. Moreover, there is an underlying economy to the compositions seldom found in progressive rock. Thematic and motivic material is constantly recycled and modified without resorting to literal repetition, which in turn grants unity and memorability to the work.

It is worth acknowledging that this analysis has barely scratched on the surface of a singularly deep work of art. Lark’s Tongues in Aspic contains an incredible amount of information that can, and has been, analyzed and interpreted very differently. As of today, several articles, books and minor treatises has been devoted to this album alone, many written by trained musicians/scholars (those readers who haven’t had enough by now are urged to check out the separate works of Gregory Karl, Andrew Keeling and Gabriel Riccio). Unless the world comes crashing down any time soon, it seems very likely that Lark’s Tongues in Aspic will continue to amaze listeners and appreciators of narrative-driven music for decades to come.

Tags: 1973, article, composition, hard rock, king crimson, lark’s tongues in aspic, metal history, music theory, narrative, progressive, progressive rock, proto-metal, review, robert fripp, through composition

Personally I believe that bands like Goodthunder, Lucifers Friend, T2 and Jerusalem were more influential to the aesthetics of heavy metal than King Crimson.

And also this band is way better:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y30lCAWj158

Not familiar enough with these bands to either confirm or deny your claim. When you say aesthetics, do you mean musical or extra-musical features? Or perhaps both?

Not in America! The influence of these bands was not present outside a small amount of record hounds at that time. King Crimson was a big influence on Tony Iommi. The pre-Spooky Tooth band Art was also a huge influence on all of Sabbath.

they might have been if anyone had ever heard of them.

> connects in a logical and meaningful

I have a beef with the idea of narrative as something that is always logical. The narratives of myth and og children – two phases in a lifecycle when humans and superorganisms of humans- haven’t quite developed their facilities of abstraction well enough to dish out well-reasoned stories and are rife with logical inconsistency, even contraction. Yet when you add the parts up they do lead to a coherent and meaningful whole.

See: first wave and profanatica who aren’t VCV nor logically progress between riffs yet write impactful whole songs that sense.

I liked your review btw..

Point taken. It might be a bit dubious to use logical in this context. Calling musical “logical” may be counterproductive as well, since it could signal a lack of feel, etc.

With that said, there are plenty of passages in both tracks that doesn’t fully add up or even make sense – especially during the more intense, semi-improvised sections where polymetric interplay is at work. However, these instances does serve a greater purpose to the whole and are definitely not arbitrary.

Sorry I sort of used the article as a springboard since it’s sort of wider notion people hold. Didn’t mean to single you out specifically.

“Yet when you add the parts up they do lead to a coherent and meaningful whole.”

I do think that you state is for the most part what the reviewer means about the narrative structure being ‘logical’.

I concur with you, this is sort of review quality that made DMU top notch. Well organized and executed review!

Thinking more about this: music, art in general, but especially music, is about making you FEEL something. I don’t know about anyone else but emotions aren’t exactly logical or rational experiences to begin with. Which is again why illogical pieces work just as well as logical ones so long as the listener feels something during. Again, why the first wave works. Hell, Bachs math music is itself a thing of beauty for most but I expect he could have gotten by playing more fast and loose on the strength of the emotional content of his melodies – which most people (I’m indifferent/bored listening to Bach) consider very endearing.

I used to structure my reviews in three phases: how it sounds, what it makes me feel, how the artists might improve. Unless trashing it obviously. I regret the third in hindsight. Art isn’t a product for anyone, especially not for critics, taste making DJs or some random person who needs a piece of music to align with their preferences (see: criticisms of Desecresy). Color me surprised if you can find substantial examples of artists who say anything to the effect of “man I’m glad Christgau and Lance Viggiano trashed our record because then we’d never have made our masterpiece.” If anything consciousness towards that sort of thing creates albums like Cold Lake or Divine Intervention.

Went off on a tangent. Anyway, just thought I’d speak out against needing every narrative to be logical; especially when the point of all these patterns is to create an experience that ultimately is anything but.

You obviously haven’t listened to a lot of Bach.

First of all, there is great emotional content in his works, but it is expressed through harmony.

It would be a mistake, however, to try and find that in an obvious exercise oriented work like TWTC.

But you can see it in very controlled tension, almost esoterically in his Offering.

Now, if you want his explicit emotionality, and unhinged drastic expression, then you must look into his cantatas…. go over his PASSIONS (Matt and John), and tell me if there is nothing deeply emotional about them.

When you say harmony, I presume that you mean functional harmony in Ionian, rather than the raw harmony itself.

Functional harmony is inherently melodic, since it goes from one place to a new place over time. (As is often the case, rhythm, melody, and harmony are inseparable from each other. Every musical entity except for a sine wave has all three).

I am quite certain that Bach never composed harmony that expresses on its own, like Wagner’s “Tristan chord”.

Oh no, I definitely mean the “raw” harmony.

And no, I do not think that there has to be an explicit “meaning” meant by the composer for it to be expressive.

Harmony is inherently expressive.

If you cannot feel the different colors and fluctuations that it creates even in the simplest music, then you have a lot to work on in terms of perception.

Show me a piece in which Bach uses more harmony than the standard triads.

“more harmony”? “standard triads”? Oh boy…

Who said you needed “more harmony” for harmony to be expressive?

As I said, the most basic harmony already expresses different colors.

You are repeatedly missing the point here and confusing “quantity of notes” with “communication” through different contexts.

Good music does not need the hipsterism of “made up harmonies” for it to be perceivable and meaningful. Your argument is empty and fails to address the points.

PS. I assume you have studied the countrapunctal development of harmony in Bach, or in the baroque movement in general, where chords were outlined with respect to voice interaction, with that pure “Chord-harmony” of the 19th understood in a rigid way being anachronistic to it. If not, then you are simply a stubborn idiot.

If it was the harmony itself which expressed, and not the simultaneous melodies which cause it, or the moving of one chord to the other (functional harmony, which is inherently melodic), then he would have used more than major, minor, diminished, and augmented triads.

The only case you could make is that the voicings are what make the music.

If it was the harmony itself, then all music which only uses normal triads would be the same.

“could have” not “must have”.

You are making the mistake of mistaking option for obligation.

Melody alone doesn’t do it, and most melody does not achieve great effect without both vertical and diagonal relationships.

What you are doing is like saying that it’s the rhythm of the melody that makes the music, just because every melody has a rhythm.

If it was the rhythm, then any melody with the same rhythm would produce the same effect.

If Bach did what he did through harmony, then anyone could copy his voicings and be just as good.

Harmony is a part of the music; it is the larger whole and the way this harmony is created (through multiple simultaneous melodies) that makes the music, not, as you claimed, the harmony itself.

Educational bonus: https://urresearch.rochester.edu/institutionalPublicationPublicView.action?institutionalItemId=7769

What the FUCK are you guys talking about?!

I never said there was no emotional depth to Bach. I just said I don’t like his music.

Yeah, but you called it “math music”, which is a common, but popular, misconception of Bach’s music in general.

I called attention to that specifically, since you said you did not like it with an obvious implication that it was because of a lack of emotional content.

He said that Bach could get by on the strength of his emotional melodies.

You’re reading into it then

“MATH” music, you say?

Let’s see… and please do listen to each one:

(1) From Bach’s St. John’s Passion:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rIcinMxNYBc

(2) From Bach’s Matthaus’ Passion:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0WLedpz9a40

(3) Fantasia & Fugue In G Minor – BWV 542

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5i_UZgN-OPY

Even here, can’t you feel the drawing down, the pushing forward, the carrying to new heights, the despair, anguish and hope that harmony squeezes and releases you from?

If that’s what you get out of this stuff then cool. Who am I to argue?

It’s easy to excuse your lazy insensitivity behind your wall of “everything is subjective”.

Well many beer lovers do not like stouts while many others do. Not liking stouts or Shandy’s even doesn’t make you any less of a beer lover or a person of good taste for that matter. I’d like you to think about being more respectful in these matters from now on. Thank you.

fucking Bachsucker

I can’t stand the passions, at least not the first, because I don’t exactly enjoy hearing the voices of that many people, however, I had to force myself away from the organ piece. A very cool journey through a strange landscape of gemlike notes wrought into an ever and never repeating cascade of delicate shapes, somewhat like watching waves on the sea.

Bach’s church music/cantatas aren’t to everyone’s tastes.

If you want other examples of Bach’s emotive prowess consider these:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mGQLXRTl3Z0 (Bach Cello Suite No.1)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gv94m_S3QDo (Goldberg Variations: Aria)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vrxgPYCmzEU (Concerto for Violin, Oboe, and Strings in D minor, BWV 1060 – 3. Allegro)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=asXHYt1Y25s (Well-Tempered Clavier Bk 1 BWV 846 1. Prelude & Fugue 1 in C major)

https://youtu.be/jovQnR2Tk-I (Keyboard Concerto No. 1 in D Minor)

Bachs math music

Among other things, Bach was a famous improvisor who reportedly landed his first professional engagement by wandering into a church (in a strange town) and starting to play the organ without notes.

It is also worth noting that when Bach or Bruckner improvised, they created highly structured music. Modern “improvisation” is barely related to this.

Yet many a fan of modern guitar-“virtuosos” etc. appears to think that improvisation is something magical where the artist is free to speak from his heart without restraints. What they apparently doesn’t realize is that even blues-musicians had a clearly defined set of rules (be it harmonic, rhythmic or whatever) that they employed during performance.

I agree that the “classics” had a wholly different grasp of structure when improvising that is completely lacking in (most) modern forms of music.

If I had a time machine, I would go back to hear Bruckner improvise all night as he formulated his understanding of music as a young man.

Hmm … if it wasn’t performed for an audience it probably wasn’t meant for one. I’ve spent some years teaching myself to play blues harmonica by experimenting with one (with varying success although I can at least play notes outside of the normally available range on a diatonic one) and unasked-for audiences are hugely distracting: In the end, what one wants to do is play with ideas and try sound combinations without worrying what other people may think of the result.

This is the kind of content that people actually visited this site for once upon a time – insightful reviews of music that we actually want to listen to. Hopefully there will be more of this and less of Maarat and co.’s infantile nonsense.

YES thank you. Insightful reviews of music that we actually want to listen to, vs. Mallrat’s non-insightful shitslinging at music that we never wanted to hear anyways.

The intro is a pointless three minute exercise in someone caressing ‘exotic’ percussion instruments. Gamelan fucked up for western tastes. This is followed by an attempt at being Deep Purple while maintaining that such primitive stuff is far below the band. After this has run its course, there’s a section dominated by guitar and bass circling running around each other while showcasing all kinds of effects considered fashionable in the 1970s. This is terminated by the first element of this which is sort-of likeable, some backgrounded violin playing a lonely gipsy tune. But – alas – things can’t stay that simple for long. The violin starts playing slightly ‘stranged’ chords and the guitar has to make some noises again to show that it’s still there. The violin melody comes back, this time killed by an ascension and someone talking in the background. Around the 13th minute, we get a straight rip-off from better late 60s/ early 70s bands with tiddly little additions to remind us that This Is Serious Stuff™.

The second part of this reminds of an old Velvet Undergound motto (paraphrase): “We really just wanted the audience to go away so we’d just jam randomly. If they manged to live through this for 20 minutes, we’d be jamming for 40 minutes.” This is a compositional exercise in achieving the same effect without jamming.

Have to abort this here because I need to get on a conference call. Very nice article about some very atrocious piece of music.

Some unprogressive 1970s stuff (that’s probably actually a studio jam):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Tx2vypcFYQ

Well I’m glad to hear that the article was somewhat enjoyable despite your obvious distate for this kind of music! There is really no point in arguing against your assessments, I do however enjoy your suggestions of 1960s/70s material from time to time.

In the end, I have to agree with this.

It’s a really talented show of music, but ultimately about nothing worthwhile.

muh phrases

One day i’d like someone to break free of the prozak-approved mold and talk about a prog-rock group in positive terms which isn’t fucking King Crimson.

Red and Larks are overrated jams. In the Court of the Crimson King will forever be the mind-altering, transcendental masterpiece that bookmarks this band in the history of music.

You only have to do a quick search to find them.

Also, suggestions of progressive bands worth covering is always welcome.

Maybe silly but in the context of metal, something like

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e4IVF-h10g0

would seem to suggest itself.

On its way, although it will probably be Pawn Hearts.

Excellent. That album is the peak.

Yes would be one obvious example of a band they’ve covered. also Imposition could really use a new vocalist/lyricist

Right, by reviewing the album which isn’t really a group album but a compilation of solo-compositions.

Close to the Edge, Relayer, or GTFO you pussy.

there’s also an exceedingly long lyrical analysis of Close to the Edge, tough guy.

why is it that you’re such a prog elitist but your name links to a mediocre modern metal band?

If liking Progressive Rock and liking ‘modern metal’ at the same time causes 404 errors in your brain that’s for you and your therapist to talk about fam.

Why do long-time fan-boys of ANUS (in both sense of that label) get so defensive when something that is not 100 per cent Prozak(TM) approved is floated? It’s getting oh so fucking boring.

you clearly completely missed my point and have some sort of hard-on for prozak. bravo.

i.e. We’ve all heard about King Crimson’s ‘Red’ enough. Time to talk about something new.

and indeed, about King Crimson in general.

or you could make another windy post about how they suck after Court like a pardoned hooker and then bloviate about Prozak some more

youve always been a fag with your affinity for Tool, buster.

Old anus site had positive reviews of Camel, Caravan, and High Tide as well as the aforementioned Yes.

Also, Red is an awesome album, though, I agree fully that In the Court is their untouched masterpiece.

Änglagård from Sweden, who were producing progressive rock during the height of the Stockholm death metal scene.

A review of Änglagård’s debut is coming, sooner or later…