Metal like any addiction sends us toward the next more intense experience by necessity. When we cannot find the rush in metal, we turn to other genres, but few of those satisfy. Metalheads often find themselves tempted by classical music, but shy away for a number of reasons.

Classical music requires greater attention to recording, conductor and year than do rock-style albums where artist name and album name will suffice. The choice of which of those to get appears at first baffling and ambiguous. The classical community can be a big help, but on the internet, fans of every stripe tend to have a holier-than-thou outlook which drives away others. Finally, classical cannot compete sonically with metal which is a constant delighted terror of high-intensity guitar.

For those who want to branch outward however, classical offers an option which resembles metal under the surface even if from a distance it appears the opposite. Classical music like metal is riff-based and knits those riffs together into compositions which transition between multiple emotions and forms to tell a story, unlike pop which is more cyclic if not outright static. It also embraces the same Faustian spirit of rage for order that defines metal.

The brave few might want to forge ahead with these albums which serve as good entry works to classical:

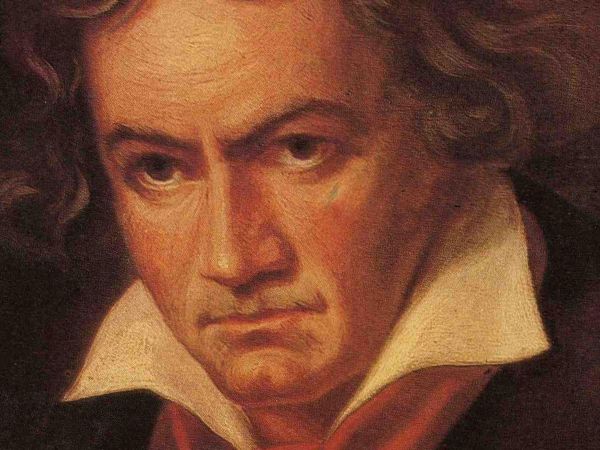

Brahms, Johannes – The Four Symphonies

Brahms, Johannes – The Four Symphonies

Pure Romanticism, which is the most beautiful classical genre but also its most easily misled into human emotional confusion. Flowing, diving, surging passages which storm through tyrannical opposition to reach some of the most Zen states ever put to music.

Four Symphonies by Herbert von Karajan/Berliner Philharmonik Orchestra

Respighi, Ottorino – Pines, Birds, Fountains of Rome

Respighi, Ottorino – Pines, Birds, Fountains of Rome

Italian music is normally inconsequential. This has an ancient feeling, a sense of weight that can only be borne out in an urge to reconquest the present with the past.

Pines, Birds, Fountains of Rome by Louis Lane/Atlanta Symphony Orchestra

Schubert, Franz – Symphonies 8 & 9

Schubert, Franz – Symphonies 8 & 9

A sense of power emerging from darkness, and a clarity coming from looking into the halls of eternity, as translated by the facile hand of a composer who wrote many great pieces before dying young.

Symphonies 8 & 9 by Herbert von Karajan/Berliner Philharmonik Orchestra

Saint-Saens, Camille – Symphony 3

Saint-Saens, Camille – Symphony 3

Like DeBussy, but with a much wider range, this modernist Romantic rediscovers all that is worth living in the most warlike and bleak of circumstances.

Symphony No. 3 by Eugene Ormandy/Philadelphia Orchestra

Bruckner, Anton – Symphony 4

Bruckner, Anton – Symphony 4

Writing symphonic music in the spirit of Wagner, Bruckner makes colossal caverns of sound which evolve to a sense of great spiritual contemplation, the first “heaviness” on record.

Romantic Symphony by Herbert von Karajan/Berliner Philharmonik Orchestra

Berwald, Franz – Symphony 2

Berwald, Franz – Symphony 2

The passion of Romantic poetry breathes through this light and airy work which turns stormy when it, through a ring composition of motives, seizes a clear statement of theme from its underlying tempest of beauty.

Symphony No. 2 by David Montgomery/Jena Philharmonic

Paganini, Niccolo – 24 Caprices

Paganini, Niccolo – 24 Caprices

Perhaps the original Hessian, this long-haired virtuoso wore white face paint, had a rumored deal with the devil, and made short often violent pieces that made people question their lives and their churches.

24 Caprices by James Ehnes

Anner Bylsma and Lambert Orkis – Sonatas by Brahms and Schumann

Anner Bylsma and Lambert Orkis – Sonatas by Brahms and Schumann

We list these by performer because this informal and sprightly interpretation is all their own. Played on period instruments, it captures the beauty and humor of these shorter pieces with the casual knowledge of old friends.

Brahms: Sonatas for Piano and Cello; Schumann: 5 Stücke im Volkston

Not everyone will take this path. Where metal, pop, rock, blues, techno, hip-hop and jazz aim for a consistent intensity, classical varies intensity as it does dynamics and mood. The point of listening to classical is to let it take you on an adventure, which much like metal will at some point encounter a crashing conclusion in which all things vast, powerful and beyond our reach come to bear on us for the ultimate feeling of heaviness.

24 CommentsTags: anner bylsma, anton bruckner, berliner philharmonik, camille saint-saens, Classical, franz berwald, herbert von karajan, johannes brahms, lambert orkis, niccolo paganini, ottorino respighi, robert schumann