The notion of a prism represents the first challenge to our early worlds of concrete time and space. A device that fragments light, and reveals a space withina solid known quantity, seems to us an expansion of dimension. As we get older, we realize the expansion of dimension occurs within ourselves as we assemble a more complex view of the universe.

Metal music as art is composed of sound and lyrics and imagery. The pure aesthetic expands as we analyze it and recognize that it is beauty found in chaos; the songwriting expands as we see that its narrative motivic composition is more poetic than the looping closed circuit cycle of rock or pop; the keyless melodic nature of it becomes in our fertile minds a sense of construction not by a “third party” of rigid harmonic theory but by the unfolding narrative. Metal music like all great art begins by appearing simple, but opens to reveal greater complexity when we look into the dimension that it creates for itself.

Metal music as art is composed of sound and lyrics and imagery. The pure aesthetic expands as we analyze it and recognize that it is beauty found in chaos; the songwriting expands as we see that its narrative motivic composition is more poetic than the looping closed circuit cycle of rock or pop; the keyless melodic nature of it becomes in our fertile minds a sense of construction not by a “third party” of rigid harmonic theory but by the unfolding narrative. Metal music like all great art begins by appearing simple, but opens to reveal greater complexity when we look into the dimension that it creates for itself.

From this alone, we might conclude that metal is prismatic in the same way modernist classical composers and the ancient Greek plays that bonded song to poetry to theatre were. Two more elements demand our consideration: that metal represents an escape from the karmic cycle as described by numerous philosophies, and that it inspires mythic imagination in the way both Sophocles and Wagner did.

***

Most of what we see in life affirms the karmic cycle. The rock music that plays from passing cars, the lighted billboards over our roads, the conversations of our friends and neighbors: who are you going to be in love with? And marriage? Or what will you buy? Where you go? How will you build your identity using material things, including your body?

This fascination might be called aphilosophical because it is not reaching for anything more than what is in front of us, one object after another, in the process of life. This is called the karmic cycle because it deals with the functions of birth and death and sustenance and nothing else. It is not an active philosophy or an aspiration toward ideals, but a continuation of what is presented to us, a reaction to life itself.

Metal music does not oppose the karmic cycle, as it is fully hedonistic, but it views it as secondary to an idealistic quest for meaning. This quest is expressed in the sound of metal, which unites beauty and ugliness in the pursuit of a kind of power, or “heaviness,” in which the burdens of life are converted to a sense of pride in not only survival but a quest for higher things. Metal bands glorify war and the occult, death and heroism, victory and defeat, without taking on that tone of self-serving lament which protest music brings.

Fear runs wild in the veins of the world

The hate turns the skies jet black

Death is assured in future plans

Why live if there’s nothing there

Sadistic minds

Delay the death

Of twisted life

Malicious world

The crippled youth try in dismay

To sabotage the carcass Earth

All new life must perish below

Existence now is futile

Convulsions take the world in hand

Paralysis destroys

Nobody’s out there to save us

Brutal seizure now we die

– Hardening of the Arteries, Slayer

Death is now the day

When the fires fall from the sky

Let us pray

When the darkness falls we will die

Endless pain

Crucifying death from above

We must pay

Day of darkness

Question our fate when day of darkness

Forces of evil now upon us

Forces of evil on display

Forces of holy brought this day

Death is now the day

When the reaper calls for the dead

We’ll be saved

In this world of desecrating minds

We must pay

Crucifying world of evil death

Let us pray

Day of darkness

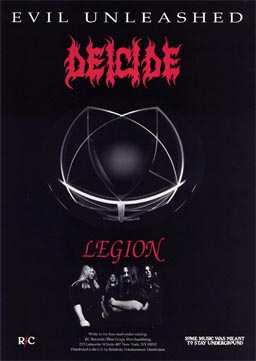

– Day of Darkness, Deicide

It is an introduction to basic transcendental theory in that metal does not deny the suffering and horror of life, nor our desires within it. More pointedly, it looks beyond them to the beauties and greatnesses that can be found in this vast unpure mix of good and bad that forms a “meta-good,” or the space of life itself in which our decisions can reward us — even if we are personally destroyed. Where rock music is a descent into the karmic cycle, metal points its gaze above it toward the ideals a karmic cycle can serve.

In doing so, metal introduces meaning through nihilism, or a denial of all except the immanent. It rejects morality and eschews religion, preferring a pragmatic idealism in which death may be final but there are things worse than death such as dishonoring oneself or becoming cowardly. It seeks to find meaning in the emotions of an individual that have accepted the logic of life as suffering and transcended it, or found meaning in existence to balance that suffering and make it less consequential. Metal tears away all of our illusions to show us life, and then reconstructs our belief in life by showing us the beauty and power outside of our artificial reality of morality, money and social esteem.

In doing so, metal introduces meaning through nihilism, or a denial of all except the immanent. It rejects morality and eschews religion, preferring a pragmatic idealism in which death may be final but there are things worse than death such as dishonoring oneself or becoming cowardly. It seeks to find meaning in the emotions of an individual that have accepted the logic of life as suffering and transcended it, or found meaning in existence to balance that suffering and make it less consequential. Metal tears away all of our illusions to show us life, and then reconstructs our belief in life by showing us the beauty and power outside of our artificial reality of morality, money and social esteem.

Among popular music genres, metal is the only one to explicitly strive for this goal, although it might be said that industrial acts like Kraftwerk or folk acts like Väsen aim for the same as exceptions to the norm. In a time when most products are tangible, and therefore require karmic fascination, and most political power is derived by tantalizing people with the reward of karmic tangibles, and all social prestige falls within the egosphere of karmic need, metal is the odd man out who has cast aside the normal trappings of life and is staring at the sky into the infinite space of his own mind and that of the universe.

***

In this idealism, or belief that thoughts and the physical world act by similar principles if they are not outright dimensions of one another, metal reawakens something that has lain dormant in humanity during its time of modernity: the mythic imagination. While our modern world deals exclusively with attempts to allay the suffering of the karmic cycle through technology, metal is geared toward finding uses for that suffering in the form of greater glories against which suffering and death become puny. In that state of mind, one has awakened not just a higher aspiration but a sense of magical possibility (miracles, dreams, a positive order beyond the visible) in which life itself is a living continuity of mind and reality.

Pascal is right in maintaining that if the same dream came to us every night we would be just as occupied with it as we are with the things that we see every day. “If a workman were sure to dream for twelve straight hours every night that he was king,” said Pascal, “I believe that he would be just as happy as a king who dreamt for twelve hours every night that he was a workman. In fact, because of the way that myth takes it for granted that miracles are always happening, the waking life of a mythically inspired people — the ancient Greeks, for instance — more closely resembles a dream than it does the waking world of a scientifically disenchanted thinker. When every tree can suddenly speak as a nymph, when a god in the shape of a bull can drag away maidens, when even the goddess Athena herself is suddenly seen in the company of Peisastratus driving through the market place of Athens with a beautiful team of horses — and this is what the honest Athenian believed — then, as in a dream, anything is possible at each moment, and all of nature swarms around man as if it were nothing but a masquerade of the gods, who were merely amusing themselves by deceiving men in all these shapes.

…

There are ages in which the rational man and the intuitive man stand side by side, the one in fear of intuition, the other with scorn for abstraction. The latter is just as irrational as the former is inartistic. They both desire to rule over life: the former, by knowing how to meet his principle needs by means of foresight, prudence, and regularity; the latter, by disregarding these needs and, as an “overjoyed hero,” counting as real only that life which has been disguised as illusion and beauty. Whenever, as was perhaps the case in ancient Greece, the intuitive man handles his weapons more authoritatively and victoriously than his opponent, then, under favorable circumstances, a culture can take shape and art’s mastery over life can be established. All the manifestations of such a life will be accompanied by this dissimulation, this disavowal of indigence, this glitter of metaphorical intuitions, and, in general, this immediacy of deception: neither the house, nor the gait, nor the clothes, nor the clay jugs give evidence of having been invented because of a pressing need.

— from On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense (1873) by Friedrich Nietzsche

A myth elides the tangible into a visible manifestation of invisible forces, only some of which can be explained by material science. Whether or not it is technically “correct” regarding the immediate causal relationship between impetus and result, it is a correct description of the cosmic order as the human sees it and feels it. There are balances between voids and solidities, certainties and doubt, horror and beauty. In the mythic state, a human being focuses less on a singular moment and singular end result than on the continuing relationship between many results and the tendency of mathematical organization to the universe they suggest.

The foremost thrust of mythic imagination into art in the modern era (post-Middle Ages) was the art of the Romantics, who in literature and painting and music and dance crafted a world where symbols were no longer literal but spoke of a personality of a living existence. They replaced God the judge of moral actions with Nature the god of function that rewarded the best, and in this more realistic view of life crafted a conception of the human being as looking inward for ways to complement this external greatness. They were not individualists in the modern sense, rewarding themselves with pleasures of the flesh, but they looked into the individual soul to find by intuition not only what was true but what was desired.

Some attack this view as “aestheticism,” meaning that it rewards that which seems beautiful instead of that which is functional, or, in the humanist view, moral. Humanism like materialism is aphilosophical in that it approaches the karmic cycle as an end in itself, and tries to preserve “freedom” and material comfort and survival for all individuals. Humanism does not recognize that a tragic death is beautiful, or a heroic death majestic, because its only concern is with maintaining the flesh and meat of human beings. Humanists claim mythic imagination is aestheticism because it sacrifices individuals to beauty and thus is amoral.

To this those who have made the journey from materialism and fear of death to the other side where death is not only accepted but seen as a challenge, by nature of the learning gained on this journey, admit gleefully to being laughing amoralists who are unconcerned by morality. In the aestheticist view, having a beautiful and meaningful life far surpasses living for the safety of morality and spreadsheet-style risk management; aestheticism sees the best life as the one lived intoxicated with the beauty and potential of existence, and that precludes safety labels, warning rails, and fear of dying. Death is certain, but life is not, and that uncertainty comes in the form of finding an “aesthetic” that bestows upon us meaning.

In this sense of the world, where the entirety of life is connected by a logical yet invisible system of purpose, it is possible to have vir or the “warlike” virtue of ancient peoples. The Greeks and every other civilization that rose from the mire of infighting over karmic goods and status possessed this warlike spirit, as Nietzsche noted, and metal reflects this in its “inhuman” sound and lack of personal, gender and desire-oriented language in its lyrics. It reaches beyond the karmic cycle for the cosmic order, and in doing so, transcends humanity to find what makes us most human: our search for meaning beyond the suffering that being alive entails.

A dream of another existence

You wish to die

A dream of another world

You pray for death

To release the soul one must die

To find peace inside you must get eternal

I am a mortal, but am I human?

How beautiful life is now when my time has come

A human destiny, but nothing human inside

What will be left of me when I’m dead?

There was nothing when I lived

What you found was eternal death

No one will ever miss you

– Life Eternal, Mayhem

When night falls

she cloaks the world

in impenetrable darkness.

A chill rises

from the soil

and contaminates the air

suddenly…

life has new meaning.

– Dunkelheit, Burzum

Tears from the eyes so cold, tears from the eyes, in the grass so green.

As I lie here, the burden is being lifted once and for all, once and for all.

Beware of the light, it may take you away, to where no evil dwells.

It will take you away, for all eternity.

Night is so beautiful (we need her as much as we need Day).

– Decrepitude I, Burzum

Where modern society in a desire for safety imposes values designed for an average person onto all of us, and assumes that our material and humanist wellbeing constitutes meaning in life, Romanticism explodes from within. It is not a philosophy of cautions, but of desires for the intangible, and as so it worships risk and conquest and a lack of fear toward the karmic existence. It transcends the desire to either live karmically, or live akarmically, because it sees karmicism as a means to an end and concerns itself only with the end: the ideal.

Where modern society in a desire for safety imposes values designed for an average person onto all of us, and assumes that our material and humanist wellbeing constitutes meaning in life, Romanticism explodes from within. It is not a philosophy of cautions, but of desires for the intangible, and as so it worships risk and conquest and a lack of fear toward the karmic existence. It transcends the desire to either live karmically, or live akarmically, because it sees karmicism as a means to an end and concerns itself only with the end: the ideal.

In this, Romanticism constitutes a philosophy because it posits intangible ideals as a balance weight to the certainty of death. It seeks a sense of unfolding; the discovery of something new in a prismatic space hiding behind the mundane. In doing so, it renovates life itself by working from within and renewing the brain in its aspiration and heroic transcendence of the karmic drag, in the exact opposite principle to modernity, which is materialism/humanism as supported by technology and populist political systems.

Its philosophy rises above life, and above categories like political and religious and cultural, because it is a principle of the highest abstraction and so can be expressed through any number of outlets. Like Zen, it is a discovery of the connection between life and mind with a slap, but unlike any other formalized system, it goes further to demand that the slap of life have a meaning, and it invents this meaning and then creates aspiration within it through its mythic imagination. Despite the overwhelming solidity of most modern art in affirming the opposite, Romanticism continues to live on.

One of its voices is metal music, whether through the seize-the-night ethos of heavy metal or the “only death is real” of underground metal. It is nihilism, but it is also idealism; it is realism, but it is also religion. Perhaps this is why every time we think heavy metal is dead it rises again, as people still seek meaning in life despite the crushing gravity of need and obligation that is modern living. Heavy metal is eternal because its truth is eternal, as for any existence there will be a potential end, and thus a need to find not only a reason why but a reason for living not just to survive but to exceed.

As this emotion was true to the existence of thinking beings in the time of the Greeks, and allowed them to rise and make one of the greatest civilizations known to humankind, it is true now and inspires those who have rejected the long path through lighted signs and fleshy desires and moneyed popularity. For those who seek more, it is a doorway. Like our souls, heavy metal is a prismatic dimension unfolding beneath us and within us, and a journey we are only too glad to undertake.

No Comments As the cultureless void of “pop culture” (more accurately known as “mass culture,” appealing to the lowest common denominator) surges upon those traditions of artistic development which have sustained high-quality minds for centuries, symphonies defend themselves by appealing to what they hope are broader audiences. In doing so, they achieve a fragile balance between the known commendables and newer or more esoteric pieces, more accurately known as being the fringes of classical music that did not merit induct into its archetype: history rewards either excellence or pure mediocrity.

As the cultureless void of “pop culture” (more accurately known as “mass culture,” appealing to the lowest common denominator) surges upon those traditions of artistic development which have sustained high-quality minds for centuries, symphonies defend themselves by appealing to what they hope are broader audiences. In doing so, they achieve a fragile balance between the known commendables and newer or more esoteric pieces, more accurately known as being the fringes of classical music that did not merit induct into its archetype: history rewards either excellence or pure mediocrity. Graf treats classic pieces as entities that while alive might benefit from upgrade to the wisdom of a progressive time, and in that state of mind he mixes a quaint style that appeals to fans of older Mozart and Haydn with a modernist twist that propels pieces forward with increasingly off-time, theatrical pauses and rhythmic expectations. It is as if Graf is a modernist who views the quaint as one of the many voices he tries to capture, and in doing so, he often loses sight of the piece as a whole, which is where he will remain a B+ and the Furtwanglers, von Karajans, Salonens, et al. will surge forward to the higher grades.

Graf treats classic pieces as entities that while alive might benefit from upgrade to the wisdom of a progressive time, and in that state of mind he mixes a quaint style that appeals to fans of older Mozart and Haydn with a modernist twist that propels pieces forward with increasingly off-time, theatrical pauses and rhythmic expectations. It is as if Graf is a modernist who views the quaint as one of the many voices he tries to capture, and in doing so, he often loses sight of the piece as a whole, which is where he will remain a B+ and the Furtwanglers, von Karajans, Salonens, et al. will surge forward to the higher grades. In the fourth movement Graf made a strong return, although like Klemperor he often prefers dramatic pauses to introduce obvious changes in theme, and complements them with a tendency to play repeated themes slowly like a movie soundtrack and elide them with rhythmic consistency and a lack of distinction for the subtleties that prepare us for their shifting. It is probably not a failing of intellectual ability on his part, but a desire to belong to the fashion that includes modernism and postmodernism, or the idea of subjecting all things to a mechanical process and controlling them through rules of self-interest which promote egoism and other out-of-context appearance of supporting structures. It can reduce complex music to a one-dimensional machine transferring energy between otherwise equal parts.

In the fourth movement Graf made a strong return, although like Klemperor he often prefers dramatic pauses to introduce obvious changes in theme, and complements them with a tendency to play repeated themes slowly like a movie soundtrack and elide them with rhythmic consistency and a lack of distinction for the subtleties that prepare us for their shifting. It is probably not a failing of intellectual ability on his part, but a desire to belong to the fashion that includes modernism and postmodernism, or the idea of subjecting all things to a mechanical process and controlling them through rules of self-interest which promote egoism and other out-of-context appearance of supporting structures. It can reduce complex music to a one-dimensional machine transferring energy between otherwise equal parts.

This image lingered in the mind for the long passage through the winding freeways of downtown Houston, through the parking lot where newsprint stained thumbs are licked to separate change for a twenty, and into the dark cavernous quiet of Jones Hall to hear Hans Graf conduct Anton Bruckner. Opening the piece with a chorus singing Bruckner’s “Ave Maria” from the lobby, Graf paused briefly and then raised his wand, to which a synchronized rising of instruments announced the descent from our world of tangible objects into the abstraction of music had become. The concert began from a silence in which the echoes of human voices still faded.

This image lingered in the mind for the long passage through the winding freeways of downtown Houston, through the parking lot where newsprint stained thumbs are licked to separate change for a twenty, and into the dark cavernous quiet of Jones Hall to hear Hans Graf conduct Anton Bruckner. Opening the piece with a chorus singing Bruckner’s “Ave Maria” from the lobby, Graf paused briefly and then raised his wand, to which a synchronized rising of instruments announced the descent from our world of tangible objects into the abstraction of music had become. The concert began from a silence in which the echoes of human voices still faded.