Evolutionary skips like humanity do not occur without the introduction of a radical new method. In the case of humans, it was language, which allowed us to form societies of larger than familial groups, specialize in certain tasks, and so preserve a massive knowledge of tools and methods that would overwhelm any human. As a result, we are smarter chimps with socialization in our blood.

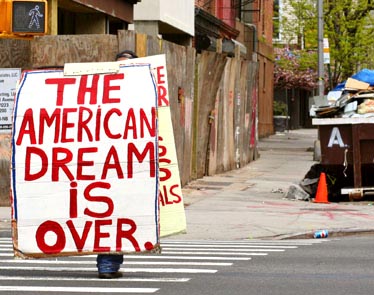

From this origin, it is easy to see why humans crave company, but approach it with an unease rooted in the need to keep a balance over social obligation and personal obligation. Too much obligation to society, and we become Stalinist slaves; too much obligation to the individual, and we become modern Americans shuttling between the shopping mall and the psychologist, wondering why we cannot fill the holes our souls with our rank, our wealth, and the possessions we pile up in our castle retreats before shipping them to third world landfills.

Too many people around us creates a hubbub that drowns out our own thoughts. In such situations, we get overwhelmed and it becomes harder to hear our own minds and memories because as we are concentrating, other voices intervene. It is like having someone talking to you when you type; inevitably, you type pieces of the conversation instead of what you meant to scribe. When we are overwhelmed by socialization, we get beaten down into accepting external trends and ideas as our own thoughts.

Someday this condition will be recognized as belonging to that indefinite area between disease and pathology where alcoholism, drug abuse, promiscuity, compulsive gambling, religious delusion and overeating fall. Just as the right dose of a compound has medicinal effect, but too much is poison, and too little is apathy, we need some degree of socialization: murder is wrong (except when necessary), don’t defecate in the water supply, help your neighbor if her house is on fire.

These thoughts are helpful when we can take them into ourselves as a logical conclusion, and realize their necessity, but when societies get too big and too unequal in the abilities of their populations, large centralized institutions or social movements occur which try to hammer these thoughts into our head. The fine line between “murder without reason creates anarchy” and “murder is bad in an absolute sense, and you’ll go to hell” is where things go wrong. If we get afraid for ourselves, and insist on making ever more rigid rules, we take American individualism and turn it into Stalinist persecution of those who step out of line.

In the same way that suffocation might be viewed as CO2 crowding out oxygen, this social overdose might be seen as nature, abhorring a vacuum as the cliche goes, flooding our minds with the will of others which magnified by the credence we give external objects for their self-evidence, take on a higher weight of appearance than our own thoughts — or observations which, while not our own, ring true with what we know from experience and analysis. Civilization can drown us in what makes it strong, which is its support network for us.

Nature thrives on complexity, and like most patterns in nature, this sequence of logical events is repeated in any situation where individual brains must form one brain for the purpose of supporting greater knowledge. One such case is that of musical genres, especially those which derive much of their power from their claim that they are an alternative view to the dominant cliche, which may be either Stalinism or Americanism, or the hybrid of the two mentioned above. Neither Stalin nor Americans invented these two extremes; they are repeated patterns formed by the constraints of nature itself in the task of uniting individuals to perform the functions required for civilization.

When such patterns form in a musical genre, equality results, because when there are too many people in a cycle they make an unspoken agreement to treat each other equally so that none are seen as aggressors. This is similar to Americanized Stalinism in that it is the fear of the individual which motivates a stronger society with more rigid rules, such that the rules themselves become the goal, instead of the avoidance or promotion of consequence that the rules were intended to cause. Fear is the cause, and the result is a type of negative thinking that presupposes bad consequences to justify radical and extreme actions taken against its possibility. As the negative thinking spreads, it dominates every form of social and political discourse, and becomes accepted as a fact of civilization itself and not an option.

This negative thinking aims to nullify possible threats instead of treat the source of threat, so it has a neutralizing effect, and soon standards lower. From the best of civilized intentions, collaboration, we produce unending compromise. The compromise arises from our fear of transgressing against well-intentioned but rigid rules, and because the rules are irrational, all other thinking becomes irrational. The individual becomes the root of all justification, and so even if the individual produces mediocrity, there is a demand that all respect that individual for the sole reason of he or she being an individual — otherwise, the negative thinking is violated, and we all will descend into anarchy (the thinking goes).

In an artistic genre, this results in tolerance for all artists which means an information overload so great that none can rise above the crowd. As a result, you have many people happy to have achieved mediocre success, because that’s where 99% of all artists are going anyway, and 1% of the artists who could do better standing alone, longing for a frontier. All suffer because they can’t promote this 1%, because those are the superstars who keep new people coming into a genre, which is necessary because fans age and drop out or die. However, they prefer on an individual level to be rockstars of their block instead of allowing others to be recognized artists who lead.

This pattern repeats itself time and again. It’s how nature sloughs off the dead and dying before they actually exterminate itself, kind of like the sudden summer colds the gods wisely designed to erode the elderly population (think quickly: die for months in a hospital bed, or get the sniffles, go to sleep and kick off in a matter of hours? if the two were methods of execution, we’d quickly decide the latter was more “humane”). If any society cannot find a balance between individual and collective, it tends toward the extremes, becomes rigid and collapses into the kind of third-world entropy we see in the ruins of past superstar civilizations and, hehe, black and death metal today.

One on extreme, in black and death metal, you’ve got the “let’s be one unit” people, or Stalinists, who call themselves “true” but are true to looking like they’re the past, but not understanding, because they’re actually there to be rockstars of the block (note that the first pose adopted by rockstars of the block is humility; it lets them manipulate other people into supporting their own mediocrity, under the guise of “helping one another” and when no one’s looking, taking advantage of the situation; a community of rockstars of the block would rapidly starve itself: “I swear, Jimbo, there was a whole bushel of grain there we were going to share! I don’t know how it got so small, but let’s split it anyway”). The faux true contingent of death metal and black metal bands take the past, put it in a blender, and then drift toward whatever their childhood influences were, which is what they were going to do anything. As a result you have Suffocation-style death metal with black metal choruses mixed into what sounds, at its core, like a Def Leppard ballad. You should buy it because it’s unique.

The other extreme are those who want to embrace the crowdthink through individualism people, or Americans, who want to make that uniqueness be the central feature of the music, but they also tend to play exactly what their childhood influences were, and spend a good deal of time neurotically trying to cover it up. To them, good music has a combination of instruments, images, or quirks never done before, so they specialize in making funk-based death metal with black metal face paint and electric tuba solos. These combinations are inherently unstable, and if you listen carefully, you can hear the Def Leppard peeking through underneath. These musicians deal exclusively in re-combined aesthetic, but never change the structure, form, or musical language of the music. It remains Def Leppard, cut up by jazz breaks and horn solos, grindcore blast beats and disco choruses.

Both extremes share one thing in common: Because the music they make is blatantly ludicrous, and at its essential level unremarkable and in fact in agonized neurotic contortions to hide its ordinariness, the “artists” adopt a pose of self-reflexive irony: “It’s supposed to be entertainment, and between you and me, most of them don’t get it. We’re laughing at ourselves! The people in the audience who know the hip joints are laughing with us, at themselves and ourselves. It’s a big, UNIQUE, party!” Unfortunately for humanity, most people are barely entering maturity when they start listening to this stuff, and it can take them another decade to take a long hard look at what they were listening to, cough, and throw in the towel. At that point, most are so cynical they expect all forms of potential truth or vision to be scams, and so embrace a Gene Simmons-style “it’s all entertainment, don’t take it so seriously” attitude. Doubly unfortunate is that they approach religion and taxes with the same attitude.

The interesting thing about patterns however is that they do not have a central controller. Instead, they emerge from a situation when multiple conditions are correct. The horde of people making stupid music would like you to believe that at some point, the hand of G-d descended upon Earth and wrote in clear Spanglish that all metal must be insincere, and either imitate the past or combine motley cliches to make a new horror of self-analytical but unprofound music. Like all things in the modern time, the pattern of clueless music emerges when a genre makes a name for itself, and then the hordes of bored kids accustomed to being lied to in the suburbs surges into the genre with the assumption that it should be as lie-ridden, popularity-dominated, and self-marketing like their parents as every other media they encounter is.

Ocean streams are another example of emergent patterns. They flow a certain way because that way is the path of least resistance for water to flow, guided by gravity and tides, shaped by shorelines and underwater formations, channeled by differentials in temperature; the paths of ocean streams are not inherent, but appear again and again because the needs of their waters are met by the situation. It’s like horses and open barn doors: you don’t need to tell them to leave, because any creature cooped in a barn wants to leave and will do so, given (a) an aperture and (b) the promise of relative impunity in escape.

What is common about emergent systems is the need for an attractor, which can either be something valuable (atoms bonding with atoms to form stable molecules) or something empty, like a void or frontier (horses rushing toward open barn door). There is in nothingness always possibility; in somethingness, there is safety, but at the expense of variability. It’s like picking a boring day job over a more chaotic self-employment, or choosing to be a domesticated dog instead of a wolf, filling your head with television instead of thinking, or deciding to stay single instead of risking a relationship in which real work must be required. Metal music requires a frontier, unfilled in nothingness, so it can have space to expand.

In this however we see the parallel roles of creation and destruction. For creation to occur, there must be empty spaces but these are only acquired through the removal of something that exists. This principle underlies both natural selection and our tendency toward, in boredom, smashing boring things. When there is too much somethingness, we must make nothingness by removing that which is and is also unsatisfying. For example, if we burned every death and black metal recording but that top slice of really profound works, would the genre be stronger or weaker? Weaker in quantity, stronger in quality, with lots of empty space in which others can visualize their musical/artistic dreams being fulfilled.

Underground metal flourished in a brief period of frontier. Indie labels were a creation of the 1980s when, with digital recording technology becoming affordable just around the corner, printing plants began to more widely open up the new digital technology of compact discs to smaller businesses. As it became possible to print just a few thousand CDs, it became possible to run a small label without it being a complete financial loss, and so indie rock and eventually, indie metal (known as underground metal: thrash, death metal, black metal, grindcore, doom metal) expanded. To distance themselves from mainstream rock, and to compensate for their lack of big bucks for flashy studios, both indie rock and underground metal embraced a gritty aesthetic that made them unpalatable to the average consumer.

However, the average consumer wants to buy something that is intangible, which is that hipness or cachet of authenticity of which rock writers rave. This is why white kids bought forbidden “race music” called the blues, even though it was essential Celtic-Germanic folk music repackaged with a constant beat and gritty vocals. This is why punk music grew rapidly once people living boring lives saw it as a chance to walk on “the other side.” This is why freaks of nature and often pointless artist from Klaus Nomi to Insane Clown Posse have always attracted an audience, because they’re “unique” and “different.” The history of rock music is of one undending scam that sells inferior music to bored kids who are seeking an alternative to the staid social lifestyle of compliance that they see in their parents, who because of their dysfunctional attitudes, treat their children like objects and are consequently covertly hated.

In metal, this desire for the other side manifested itself in Pantera making death-metal-like albums for the real meatheads out there, Cannibal Corpse making a parody of death metal (later parodied by art rock band Fetid Zombie) that had enough groove and bounce for the masses, and eventually, in boutique black metal like Ulver and trend-oriented death metal like Opeth, as well as a horde of “blender bands” who throw past successes into a blender, make an incomprehensible melange, and then wrap it around the same three-chord boring moron rock music that has afflicted the “culture” of industrialized nations since the 1950s.

Frontiers are the antidote to this, but they must begin in destruction. Idiots will tell you destruction is bad, because in their view, more metal means more power in metal. However, life is a science of pattern organization, and this is why patterns of higher organization (complexity) trump those of lower organization; this is why one Beethoven outshines 6,000,000 rock bands and forces their fans into denial of their inferiority. Idiots naturally feel defensive when they develop the resulting inferiority complex, so they come up with endless insincere excuses for why they should continue to listen to stupid music instead of facing reality and finding better music: we like it, it’s unique, every person has musical taste that is unrelated to their mental capacity, it’s our right to like garbage if we want, stupid music is more profound because it has a perspective contrary to the ruling classes, and so on. It’s all mental chewing gum that will keep a brain noshing, trying to find the substance, until it realizes that these statements are broken tautologies of the form “this is important because it claims to be important,” and then moves on.

Artists long for frontiers because they understand the odd relationship between creativity and power. We all want to feel power in life so we can think that our time was well spent as we lie on our deathbeds, and before, as we question daily whether we should keep going. Power is felt by having the ability to change things for the better, and this ability is afforded by looking at life, understanding the rules of nature, and using our creativity to find a way to work greatness within those rules. Freedom is not the answer, because freedom in human minds means no rules, which means our creativity has nothing to chew on, so we make garish “unique” and uniquely useless melanges instead. For creativity to thrive, we need an empty space in which to exert our power, like ancient men approaching their fields and streams and leaving behind farms and windmills irrigating them.

For those who want a frontier in metal, the path is clear. We must laugh at the now-dead past of fifteen years of unsuccessful metal which was “good enough” but never really good, and as we laugh, smash it aside. We do not need greater numbers. We need better fighters. We need bands on the level of Black Sabbath, Slayer, Morbid Angel, Burzum and Gorguts in order to make for ourselves a new space in which healthier metal can grow. For those of us who are not active musicians, this starts in intolerance of garbage music, progresses to its destruction, and then manifests itself in the tolerance of a gardener: we accept everything, but ignore all but the exceptional, and since we water that exceptional and nurture it, we let nature carry off the rest to an early death. This is both natural selection and common sense: if you tolerate everything, you will never have great things, but if you focus on the great, you will bring more of it upon yourselves.

Metal exists in a dual state of brain/body because of its hybrid origin in soundtracks/rock music, even though it was a fundamental rebellion against the careless hippie music of the time which introduced non-solutions as a good way to stay oblivious and justify personal profit, sexual conquest and hedonism despite the obvious need for hard work to resurrect a confused and dying civilization. Metal brought us back to the heavy, but because people living pointless lives like easy solutions and would like to think that buying a CD means they can “walk on the wild side” and feel OK with their mediocrity, it fights this dual nature. It’s 25% Demilich-Burzum fans, and 75% Cannibal Corpse-Skinless fans. However, as the morons fill every available space with garbage, there’s room for the 25% to return in vengeful fashion, mocking and burning the stupid, and opening up a frontier horizon for exploration.

1 Comment