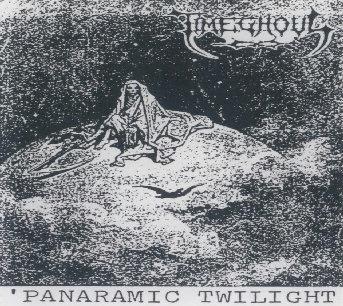

TIMEGHOUL are one of those death metal rarities: a band with only demo-level output that often outshines that of their more well known peers. Their brand of American-styled death metal was complex, eclectic and, most importantly, constructed on a foundation of solid songwriting and and intriguing concept. Guitarist Gordon Blodgett was kind enough to speak to us about their obscure legacy.

TIMEGHOUL are one of those death metal rarities: a band with only demo-level output that often outshines that of their more well known peers. Their brand of American-styled death metal was complex, eclectic and, most importantly, constructed on a foundation of solid songwriting and and intriguing concept. Guitarist Gordon Blodgett was kind enough to speak to us about their obscure legacy.

Taken and adapted from Heidenlarm ‘zine, Issue #8.

I promised no generic questions, but since TIMEGHOUL still ranks among the obscure, a brief history would be helpful here.

The band was originally formed in 1987 by Jeff Hayden and Mike Stevens. It was originaly called Doom’s Lyre, and was changed not too long after. They recruited Chad and Tony around 1990 and cut the demo Tumultuous Travelings in April 1992. Jeff wanted to go to a three-guitar attack so that he could incorporate three-guitar harmonies. At this time Mike had decided to drop out and form a Christian metal band. I grew up on the same street as T.J. and we had been playing and writing music on our guitars in his garage, but we couldn’t find anybody in 1993 that wanted to play technical thrash/death. I saw a flyer posted at the record store about Timeghoul tryouts. I followed up, tried out, made the band, and got T.J. in the band as well. Somewhere in there Chad bowed out but we continued on. We then recorded Panaramic Twilight.

Getting the second generic question out of the way: although TIMEGHOUL can be described as death metal, the eclecticism points to a greater array of musical influences. Can you describe what some of those were? What about non-musical ones?

Jeff was the main visionary here. His favorite was Atrocity’s Longing For Death, Suffocation, Immolation, Gorguts, Morgoth, Nocturnus, Malevolent Creation, stuff like that. That pretty much went for everybody in the band back then. Jeff also liked alot of experimental dark classical music from the 20th century too, as well as medieval music.

Only six tracks were officially released, but I have seen listings for live bootlegs showing more than six tracks being performed, though I have not seen the videos themselves. Is there unreleased material floating around, and is it recorded anywhere if so?

Nothing of good sound quality. There was an instrumental version of a song called “Last Laugh” that was scrapped for parts to other songs. We were also rehearsing “To Sing With Ghosts” and “Joust Of The Souls” before we disbanded, but there are only 4-track versions of the various riffs.

What comprises a “riff” in a TIMEGHOUL song? How are these presented cohesively within a song, i.e. is there a current of an idea defining each track, are the riffs composed randomly but placed in logical sequence, or is it totally random? Something else?

For Timeghoul a riff was more or less a sequence of smaller phrases that added up to a much bigger overall part of the song. Not to lose you with musician talk but Jeff was thinking like a classical composer and the riffs had the longest phrases to them — they just went on and on, and he didn’t like to come back to parts either that much, just like in classical music. As far as the format of the songs goes, I think Jeff just wrote the riffs chronologically (w/ an exception of a riff or two) as they appear in the structure.

“No man is an island.” Much as we may feel and act as Individuals, our race is a single organism, always growing and branching, which must be pruned regularly to be healthy.

This necessity need not be argued; anyone with eyes can see that any organism which grows without limit always dies in its own poisons.

– Robert A. Heinlein, Time Enough for Love (1973)

Was TIMEGHOUL tuned to A? Some of the riffs completely bottom out.

Actually we were not really downtuned at all. We tuned to E flat because nobody else was doing it. We used active pickups and played 4th chords to beef up the sound. Back then 7-strings were barely around. I think Morbid Angel, Korn, and Dream Theater were the only ones using them. We used alot of heavy EQing. Jeff actually used super-thin strings because he said it helped him speed-pick better. And T.J. and I were on the other end of the spectrum playing are jazz-gauge strings.

I think the approach to death metal taken by TIMEGHOUL can safely be called “American” for the most part. Does this mean anything to you? What makes American music in general specifically American in your opinion?

Well, I know we didn’t sound a black metal band from Sweden. We were in talks w/ Holy Records from France and they wanted to see what we came up with next before they would sign us. When the label heard the recording of the two songs from ’94 they said we sound like an American death metal band similar to Immolation with too much grinding. It wasn’t avant-garde enough for their label. I guess so. It sounded pretty unique to me. As far as an American sound goes, I would say that maybe there’s more of a focus on groove with catchy hooks or something, like Obituary I suppose. But again we weren’t writing catchy hooks or grooving. We were musically in the world created by Jeff’s lyrics.

TIMEGHOUL’s music is quite complex, but clearly not in a contrived sense. Did TIMEGHOUL strive to make complex music, or did complex music better fit the thematic ideas behind the band?

I think Jeff developed his own style of writing melodies in a midieval way, and the rest in a frantic way that begged for strange and technical patterns. He developed the Timeghoul “Vocabulary” as we used to say.

I have seen the TIMEGHOUL lyrics described as “fantasy,” which seems true. Like all good fantasy though, some seem to be truth buried under complex metaphor. They are also very well composed. Was there any kind of meta-concept, or were they written as seperate short stories that happened to play out well as lyrics?

I have seen the TIMEGHOUL lyrics described as “fantasy,” which seems true. Like all good fantasy though, some seem to be truth buried under complex metaphor. They are also very well composed. Was there any kind of meta-concept, or were they written as seperate short stories that happened to play out well as lyrics?

Jeff wrote the lyrics after the song was written. He may have had an idea or working title to the songs before the vocals were done, but that came last. Phenomenal lyric guy. I know “The Siege” has a backdrop of a castle being overtaken by the opposing army-which is metaphorical for someone going insane. I think “Rainwound” is loosely based on Greek/Norse mythology, and “Gutspawn” was based on a creature from D & D called the “Gut.” “Occurance on Mimas” was fascinating in that Mimas is an actual moon of Saturn, but it’s missing a chunk of itself. The theory was that there were evil, warring tribes on that part of the moon and an asteroid came through and knocked that part of Mimas to Earth where it all crashed into what is known today as the Himalayan Mountains. The creatures awaken from underneath and rise to the surface where they destroy the planet, before going back underground. Maybe that was metaphorical for the “underground” scene in music rising up at some point.

The “clean” vocals provide a wonderfully ethereal effect and are included with good taste. I have an old interview where Jeff Hayden mentions medieval polyphonic music as an influence on them. Was their inclusion seen as a bold move for a full-on death metal band at that point in time?

Definitely. I think Fear Factory was about the only band doing that back then. Jeff was a composer first and foremost, and he wanted harmonies everywhere, especially sandwiched between the heaviest of riffs. The songs are really progressive if you think about it. And they’re always shifting in different directions to keep it interesting.

In your experience, what works better for songwriting: democratic participation, or a more singular vision? Is there a compromise between the two? How did TIMEGHOUL typically operate?

In the band I play in now (Gate 7; what a shameless plug), we have found through trial and error that it’s best to compromise. We write everything live in the practice room, and if somebody doesn’t like it we don’t play it. As far as getting the most artistically out of a song you should probably just let an individual write the whole thing based on his/her specific vision, and then maybe the rest of the band can add their thing over the top, or make a suggestion here or there. I know when I solely write for my projects, nine times out of ten I accomplish exactly what I was going for. I can see both sides of the coin on this one.

Band members, when asked about what they were aiming to achieve, often give an answer to the effect of “Nothing — we were just four dudes playing what we loved and having fun.” This is a believable (and understandable) scenario, but not a wholly satisfying one, particularly for bands that showed greater insight. What answer would you give to this question with regard to projects with which you have been involved?

I was 18 when I joined Timeghoul in January ’94 so I was thrilled to be in a band that heavy and that original. I learned a ton from Jeff and Tony. When I write music now the songs end up being long, and I don’t like to repeat parts too many times either. It was a great learning experience to go into the studio as well. My first taste of playing live was during this time too. I think we were proud of the songs we played and envisioned sticking around alot longer than we did.

Is music art? Is modern music art? Is there a continuum?

What is art? I look at it like that about half the time. I listen to King Crimson and stuff like that, and that music makes you think the whole time you listen to it. Then I’ll put on something on from back-in- the-day and just start jamming out and having fun. Ultimately I would say I like an approach of a band like Opeth who can give you the “art” and the “heavy” at all times.

Everything that depends on the action of nature is by nature as good as it can be, and similarly everything that depends on art or any rational cause, and especially if it depends on the best of all causes. To entrust to chance what is greatest and most noble would be a very defective arrangement.

– Aristotle, The Nicomachean Ethics (c. 325 BC)

What qualities do you seek in music?

Originality and Creativity. It seems that it’s harder and harder to find original bands anymore. Everybody sounds like “this” meets “that” and it’s pretty uninspiring. I watch the new Headbanger’s Ball and for every one video that’s good there are six that either suck, or sound like something that was done ten years ago. I try my best personally to write things that are unique and don’t sound like any one band, especially over the course of an album.

Why are some people more discerning when it comes to music (or any other complex choice) than others? Is there a more-or-less inverse linear relationship between quality/quantity?

It could be a left-brained or right-brained thing. I know people with IQs through the roof, and they seem genuinely entertained by nothing but the simplest pop music of the day. Maybe their enjoyment is that they don’t have to think about it. I get my enjoyment by listening to the structures of songs, and seeing where they go, what effects the band is using, and generally how fresh the material is at the time in which it was written. I guess I do view music as art. Others may view it as entertainment, and some may listen for the message. To each their own.

Why did TIMEGHOUL fail to achieve greater success? Do you think the band was possibly too cerebral? Too different? Or was it the just result of an oversaturated underground?

The problem back then was that nobody had any money, and the technology wasn’t there to record at home on the computer, so without some support we could never record any songs. And the labels weren’t calling us because we just weren’t out there enough for them to know who we were. Plus, we could never keep a full lineup in tact. We virtually had no bass player for the final three years. Eventually Jeff and Tony had kids, T.J. moved to Florida, and I joined another band.

Has anybody shown interest in re-issuing the TIMEGHOUL material?

I will eventually post all six songs on my website (http://www.aegea-synergy.com) on the Timeghoul page (w/ kind permission from Mr. Hayden of course). I still talk to Tony and Jeff here and there. You never know — Tony lives in a home/studio with his band, and Jeff talks about writing something more ferocious and complex than ever. If we can ever find the time I would love to record some more of Jeff’s compositions. “Stay Tuned!”

Have you met with any success with AEGEA and SYNERGY?

I haven’t really marketed the music other than posting a website. It’s mainly just a hobby for me while I play in a band and live the married life. Besides, it’s hard to find a market for heavy-progressive- instrumental music (Aegea), and the other project (Synergy) is like Frank Zappa metal or something.

Was TIMEGHOUL highly revered locally? What was the response like in other parts of the US/world?

Back in the early-to-mid-90s there were hardly any any thrash and death metal bands in St. Louis. The whole grunge thing was going on and everybody thought they were born-again hippies or something. Timeghoul was always playing gigs with the same bands, like Psychopath and Immortal Corpse, but that was about it. We also opened for a show that featured headliners Obituary with Agnostic Front, Cannibal Corpse, and Malevolent Creation.

Enlightened to the point of bewilderment

Deaf to the song of creation

Blind to the light of the afterworld

What has always been shall always be

– Jeff Hayden (TIMEGHOUL), “Infinity Coda,” Tumultu

ous Travelings (demo 1992)

No CommentsTags: death metal, interview, timeghoul

For kicks I decided to listen to nothing but classical music for a month. Having bounced around looking for the next genre to capture the power of old school metal, I realized that none were coming close, so skipped the drama and went right for the heavyweight — classical. In specific, I’d found the following frustrations:

For kicks I decided to listen to nothing but classical music for a month. Having bounced around looking for the next genre to capture the power of old school metal, I realized that none were coming close, so skipped the drama and went right for the heavyweight — classical. In specific, I’d found the following frustrations: Because of this, I chucked aside the notion of listening to popular music — at all. Even if it’s underground or indie, if it’s in the popular music format, that’s how it will be perceived and treated, which in turn affects how I’ll have to interact with it and get ahold of it. Specifically, I noted how the greatest artists were straining to escape the kiddie music ghetto, like Tangerine Dream, Kraftwerk, Fripp and Eno. Why keep pushing the dead agenda?

Because of this, I chucked aside the notion of listening to popular music — at all. Even if it’s underground or indie, if it’s in the popular music format, that’s how it will be perceived and treated, which in turn affects how I’ll have to interact with it and get ahold of it. Specifically, I noted how the greatest artists were straining to escape the kiddie music ghetto, like Tangerine Dream, Kraftwerk, Fripp and Eno. Why keep pushing the dead agenda? Finally, there’s a time difference. Rock music is three-minute songs, with a few exceptions. Classical music has some three-minute songs, but more commonly, longer pieces are composed of several movements. Themes are shared across these movements, like a conversation with question, answer, debate, modification and restatement. You can’t hum a melody knowing that in thirty seconds, after the chorus, it’ll be back.

Finally, there’s a time difference. Rock music is three-minute songs, with a few exceptions. Classical music has some three-minute songs, but more commonly, longer pieces are composed of several movements. Themes are shared across these movements, like a conversation with question, answer, debate, modification and restatement. You can’t hum a melody knowing that in thirty seconds, after the chorus, it’ll be back. TIMEGHOUL are one of those death metal rarities: a band with only demo-level output that often outshines that of their more well known peers. Their brand of American-styled death metal was complex, eclectic and, most importantly, constructed on a foundation of solid songwriting and and intriguing concept. Guitarist Gordon Blodgett was kind enough to speak to us about their obscure legacy.

TIMEGHOUL are one of those death metal rarities: a band with only demo-level output that often outshines that of their more well known peers. Their brand of American-styled death metal was complex, eclectic and, most importantly, constructed on a foundation of solid songwriting and and intriguing concept. Guitarist Gordon Blodgett was kind enough to speak to us about their obscure legacy. I have seen the TIMEGHOUL lyrics described as “fantasy,” which seems true. Like all good fantasy though, some seem to be truth buried under complex metaphor. They are also very well composed. Was there any kind of meta-concept, or were they written as seperate short stories that happened to play out well as lyrics?

I have seen the TIMEGHOUL lyrics described as “fantasy,” which seems true. Like all good fantasy though, some seem to be truth buried under complex metaphor. They are also very well composed. Was there any kind of meta-concept, or were they written as seperate short stories that happened to play out well as lyrics?

Coming from the anarcho-punk school of musical and ideological tradition, and finally releasing this, their debut full length in 1985, Amebix had already released a series of excellent EP’s in the early half of the decade. The unique character of their music was a sound that fused the violent hardcore punk of Discharge with the circulative, repetitious song structures that were a staple of post-punk acts such as Killing Joke and Public Image Ltd. Escaping the social-activist themes that were a staple of hardcore, and transcending the melancholia and fatalism that was a common theme of post-punk, Amebix took on board the musical apparatus of both substyles and turned towards a contemplative, naturalistic direction that subverted the generalisation of how we associate themes with forms. Inspiration comes additionally from the NWOBHM of early Motorhead and Judas Priest in the crunching, percussive guitar playing that made itself a staple of speed metal and subsequently death metal. Drums batter clearly as if to stadium anthems, and boom with an echo one would clearly associate with said decade. Droning riffs make an appearance and have a harmonic depth to them that evoke the archaic and the dystopian much like Burzum and Godflesh simultaneously would do in their most prominent work. Whereas the metal subgenres of the 1980′s slowly influenced one anothers musical language, Amebix single handedly introduced new themes and formats that would become the structural basis of future acts to come, and alongside their compilation album No Sanctuary, this important work deserves it’s applause.

Coming from the anarcho-punk school of musical and ideological tradition, and finally releasing this, their debut full length in 1985, Amebix had already released a series of excellent EP’s in the early half of the decade. The unique character of their music was a sound that fused the violent hardcore punk of Discharge with the circulative, repetitious song structures that were a staple of post-punk acts such as Killing Joke and Public Image Ltd. Escaping the social-activist themes that were a staple of hardcore, and transcending the melancholia and fatalism that was a common theme of post-punk, Amebix took on board the musical apparatus of both substyles and turned towards a contemplative, naturalistic direction that subverted the generalisation of how we associate themes with forms. Inspiration comes additionally from the NWOBHM of early Motorhead and Judas Priest in the crunching, percussive guitar playing that made itself a staple of speed metal and subsequently death metal. Drums batter clearly as if to stadium anthems, and boom with an echo one would clearly associate with said decade. Droning riffs make an appearance and have a harmonic depth to them that evoke the archaic and the dystopian much like Burzum and Godflesh simultaneously would do in their most prominent work. Whereas the metal subgenres of the 1980′s slowly influenced one anothers musical language, Amebix single handedly introduced new themes and formats that would become the structural basis of future acts to come, and alongside their compilation album No Sanctuary, this important work deserves it’s applause.

Following up the band’s debut album Tol Cormpt Norz Norz Norz, Impaled Nazarene opened the silo once again to release their deadliest missile of truly

Following up the band’s debut album Tol Cormpt Norz Norz Norz, Impaled Nazarene opened the silo once again to release their deadliest missile of truly