Contacts: Alex Perialas, Pyramid Sound Andy Adelewitz, PR consultant

Contacts: Alex Perialas, Pyramid Sound Andy Adelewitz, PR consultant

Phone: 607.273.3931 Phone: 607.257.0455

Email: alex@pyramidsoundstudios.com Email: andy@adelewitz.com

Pyramid Sound, Where Timbaland, David Gray, Anthrax and Others Recorded, At Risk From City

Bridge Construction Supporters Organize Protests, Petitions To Save Successful Ithaca Recording Studio

ITHACA, N.Y., June 21, 2012 — The future of a world-class recording studio that has hosted recording sessions by David Gray, Anthrax, Ginuwine, Aaliyah, Bad Religion, Missy Elliott, Joe Bonnamassa, producers including Timbaland and Tom Dowd, Pulitzer Prize winning composer Steven Stucky, classical pianist Malcolm Bilson, and many others is under threat due to the City of Ithaca’s poor planning of a bridge rebuilding project directly outside the studio walls.

Pyramid Sound, the studio operated for nearly four decades by producer/engineer Alex Perialas in downtown Ithaca, New York, has been unjustly condemned as of Tuesday, June 19, resulting in the devastating loss of a very successful business, and the potential destruction of its facility as the bridge construction gets underway.

After two years of asking for details of the construction plans and how they would affect his property, and being put off by then-mayor Carolyn Peterson and superintendent of public works Bill Gray, Perialas finally got an answer about when the project would commence when workers posted signs outside his studio warning the public that the street would close in two weeks. And as of yesterday, both the studio the separate storage garage next door, which Perialas also owns, have been posted by the city, after repeated promises from the

building department commissioner that they would not be; and no one, including Perialas, is allowed in.

Additionally, the building department employee who posted the building yesterday informed Perialas that the city had found his building condemnable two years ago, in the early planning stages of the bridge reconstruction. Perialas was unaware that an external inspection of his property had happened, and was never informed of the finding, leading to at least the appearance that he was deliberately kept in the dark until it was too late to mitigate problems with his facility, allowing the city to save money by condemning his property rather than compensating him under eminent domain or amending the unnecessarily aggressive construction

plans.

It marks the latest, and most grievous, in a series of bad-faith dealings with Perialas by the City of Ithaca. The story begins in 2004, when construction of a municipal parking garage across Clinton Street from Pyramid began. Seismic vibrations from that project resulted in cracks in the walls of the garage and studio buildings,

causing some damage. He complained to the city at the time, but was unable to see the fight through because he was simultaneously caring for his ailing father.

In May of this year, after being stonewalled by city officials for two months, Perialas received a report from a third-party structural engineer hired by the construction contractor in May. The report found the storage garage, which was closest to the bridge construction, to be in poor condition, and the external walls of the studio building itself to be in poor-but-stable condition; the method of pile driving that would be used on the bridge project would likely cause the nearest garage wall to collapse, representing a danger to occupants and the public. However, this report came two weeks after the bridge project was started, leaving Perialas with no

time to repair or reinforce his buildings. Yet the City of Ithaca has offered Perialas no meaningful compensation or assistance, and has refused to delay the project or issue a change order instructing the contractor to use an alternate, less aggressive method of pile driving that would not represent so great a threat to this thriving business.

After several meetings with new mayor Svante Myrick, Perialas was finally offered just $20,000 from the city to help cover the cost of reinforcing the garage wall. But that offer came just a day before drilling to prepare holes for the pile driving was scheduled to begin — too little, too late. And it came with the unacceptable

condition that Perialas indemnify the city against any further damages to his property caused by the bridge project.

Now that the buildings have been posted, Perialas is left with a slew of recording and mixing commitments that he’s unable to complete, as well as millions of dollars’ worth of sensitive equipment that he’s unable to check on or maintain. For example, the studio’s mixing board could overheat easily if the facility’s air

conditioning system were to fail, potentially causing a catastrophic fire; but with the building condemned, no one is able to monitor the studio’s climate conditions.

Perialas makes it clear that he’s not opposed to the bridge project in general, merely the way it’s been planned and executed without any timely consultation with him, despite his many inquiries over the last two years.

“There’s no doubt that this work is needed,” Perialas told the local weekly newspaper The Ithaca Times last week. “My concern is how it’s been handled. Normally when you do a project of this nature, you work with the property owner to deal with loss of business or interruption of business. You deal with them to talk about how

you’re going to shore the building if there’s going to be an issue, and none of that’s happened. The only thing that’s happened is that I’ve had to raise my voice, unfortunately, which I don’t really want to do. I’m not anti this project. I’m anti-the planning of this project.”

Perialas and his team have received vocal support from hundreds of local musicians and music fans who are horrified by the prospect of this historic local institution being shuttered, especially under such heartless circumstances. Two Facebook pages organized by supporters in order to protest the city’s disrespect and inaction have attracted more than 1,300 members between them, and led to the organization of a protest last week at the mayor’s parking space outside City Hall.

And an online petition urging Myrick to “do all in his power to ensure Pyramid Studio be fairly compensated for any and all lost business and possible relocation costs due to this bridge construction project” has received more than 600 signatures and counting.

In addition to signing the petition, supporters of Pyramid Studios (and of the rights of responsible business owners in general) are urged to contact City of Ithaca officials including mayor Svante Myrick (607.274.6501, svante@myrickforithaca.com), superintendent of public works Bill Gray (607.274.6527, email his executive assistant Kathy Gehring at kgehring@cityofithaca.org), building department

commissioner Phyllis Radke (607.274.6508, pradke@cityofithaca.org) and city attorney Aaron Lavine (607.274.6504, attorney@cityofithaca.org) to courteously express their support for the survival of Pyramid as both a local institution of international renown, and a successful local business deserving of respectful, good

faith negotiation, and fair compensation for damaged property and lost business.

More information in recent local media coverage:

WENY-TV (ABC affiliate in Elmira, NY)

http://blip.tv/wenytv/battle-on-the-bridge-6214476

The Ithaca Times (weekly):

http://www.ithaca.com/news/ithaca/article_00af9f6e-b4e6-11e1-bd5b-0019bb2963f4.html

YNN (local TV news):

http://centralny.ynn.com/content/top_stories/588030/future-uncertain-for-pyramid-sound-studios/

ALEX PERIALAS / PYRAMID SOUND SELECTED DISCOGRAPHY

Pop/Hip Hop/R&B//Rock/Blues

Year Album Artist Role

1984 Live at the Inferno Raven Engineer

1985 Speak English or Die S.O.D. Producer, Engineer, Mixing

1986 Slow Train Savoy Brown Engineer, Mixing

1987 Legacy Testament Producer, Engineer, Mixing

1987 Power Chords, Vol. 1 Various Artists Producer

1988 New Order Testament Producer, Engineer, Mixing

1988 State of Euphoria Anthrax Associate Producer, Engineer

1989 Practice What You Preach Testament Producer, Engineer, Mixing

1990 When The Storm Comes Down Flotsam & Jetsam Producer, Engineer, Mixing

1991 Deeper Into the Vault Various Artists Music Coordinator

1992 Foul Taste of Freedom Pro-Pain Producer, Engineer, Mixing

1992 Live at Budokan S.O.D. Producer, Engineer, Mixing

1993 I Hear Black Overkill Producer, Engineer, Mixing

1993 Substance & Soul Last Tribe Producer, Engineer, Mixing

1995 Belladonna Joey Belladonna Producer, Engineer, Mixing

1995 Concept Sam Rivers Mastering

1995 Under Pressure Such a Surge Producer, Engineer, Mixing

1996 Ginuwine…The Bachelor Ginuwine Engineer, Assembly

1996 Sell, Sell, Sell David Gray recorded at Pyramid

1996 Metal of Honor T.T. Quick Producer, Engineer

1996 Oz Factor Unwritten Law Engineer

1997 Signs of Chaos: Best of Testament Testament Producer, Engineer, Mixing

1998 No Substance Bad Religion Producer, Engineer

1998 Step Beyond Without Warning Producer, Engineer, Mixing

1998 Wrong Side of Memphis Johnny Dowd Re-mastering

1999 Ginuwine The Bachelor (Bonus CD) Ginuwine Engineer, Assembly

1999 Pictures from Life’s Other Side Johnny Dowd Mastering

2000 Bronx Casket Co. The Bronx Casket Co. Mixing

2000 Looking Up Cooter Mastering

2000 New Day Yesterday Joe Bonamassa Producer, Engineer, Mixing

2000 Phubar Phungusamungus Mastering

2000 Positive Friction Donna the Buffalo Mastering

2000 Red Is the Color Sunny Weather Mastering

2000 This Day John Brown’s Body Engineer

2001 Best of 2001 Edition (Master Series) Pro-Pain Producer, Engineer, Mixing

2001 Faust Original Soundtrack Producer

2001 Hillside Airstrip 10 Foot Ganja Plant Mastering

2001 Legends of the Nar Dead Cat Bounce Mastering

2001 Temporary Shelter Johnny Dowd Engineer, Mastering, Mixing

2002 Allophone Addison Groove Project Mastering

2002 EP Sunny Weather Engineer, Mastering, Mixing

2002 Into the Unknown Double Irie Mastering

2002 Live From the American Ballroom Donna the Buffalo Engineer, Mastering, Mixing

2002 Pawnbroker’s Wife Johnny Dowd Mastering

2002 Punk Rock Songs: The Epic Years Bad Religion Producer

2002 Sing Desire Jennie Stearns Engineer, Mastering, Mixing

2003 At First Sight Pete Pidgeon Mastering

2003 Farewell The Dent Producer, Engineer, Mixing

2003 Wait Til Spring Donna the Buffalo/Jim Lauderdale Engineer

2004 Bigga Than It Really Is GFE Engineer, Mixing

2004 Home Speaks To the Wandering Dead Cat Bounce Mastering

2004 Radioman Dwight Ritcher Mastering

2005 Life’s a Ride Donna the Buffalo Producer, Engineer, Mixing

2006 Each New Day Sim Redmond Band Mastering

2006 In Flight Radio In Flight Radio Producer, Engineer, Mixing

2007 W.O.A. Full Metal Juke Box, Vol.2 Various Artists Producer

2007 Conch moe. Engineer

2007 Again We Bleed God Size Hate Mixing, Mastering

2007 Heavy Metal [Box Set] Various Artists Producer

2007 Burning at the Speed of Light Thrasher Mixing, Engineer

2007 Heavy Metal Box [Rhino] Various Artists Producer

2007 Standing the Test of Time Attacker Producer

2008 Drunkard’s Masterpiece Johnny Dowd Mastering

2008 Ginuwine…The Bachelor/100% Ginuwine Engineer, Assembly

2008 Until the Ocean The Horse Flies Engineer

2008 Room in These Skies Sim Redmond Band Mastering

2008 Aneinu! Hasidic Orthodox Music Moshe Berlin Mastering, Re-mastering,

Editing

2009 Machines of Grace Machines of Grace Engineer

2009 Infidel At War Producer, Engineer

2010 Bitten by the Beast David “Rock” Feinstein Mixing

2011 I Put My Tongue On Window Boy with a Fish Overdub Engineer

2012 Performing The Score Malcolm Bilson/Liz Field Engineer, Mixer, Post Production supervisor

2012 No Regrets Johnny Dowd Mixing, Mastering

2012 The Blind Spots The Blind Spots Producer, Engineer, Mixing

2012 Late Last Summer Dick &Judy Hyman Engineer, Mixing, Mastering consultant

Classical

Year Album Artist Role

1976 Like A Duck to Water Mother Mallard’s Portable Digital Mastering

1983 Anatidae David Borden’s Mother Mallard Producer, Engineer

1997-2006 Selected live performances and recording sessions for Cornell Glee Club and

Female Chorus Engineer, Mixing, Mastering

1997 Echos From the Walls Cornell Glee Club Engineer, Editing, Mixing, Mastering

1999 1970-1973 Mother Mallard’s Portable Producer

2001 High Rise Xak Bjerken Engineer, Mixing, Mastering

2002 Liberación Amy Glicklich Recorded, Engineer, Mixing,

Mastering

2004 In Shadow, In Light: Music of Steve Stucky Ensemble X Engineer,

Editing, Mixing, Mastering

2005 Judith Weir: The Consolations of Scholarship Ensemble X

Engineer, Editing, Mixing, Mastering

2007 Midnight Prayer Joel Rubin Digital Editing, Mixing, Digital

Mastering

2007 Under The Bluest Sky David Parks Engineer, Mixing, Mastering

2011 The St. Petersburg Chamber Philharmonic Engineer, Mastering

2011 Horn Muse CD Gail Williams Engineer

Television Credits

Year Show Channel/Institution Role

1999 Swiftwater Rescue Discovery Pictures Engineer, Mixing

1999 Wildlife Legacy Turner Original Productions/National Wildlife Federation Engineer, Mixing

1999 Wild City Turner Original Productions/National Wildlife Federation Engineer, Mixing

1999 The Legends Series Turner Broadcasting Engineer, Mixing

2000 Detonators: Sheer Force BBC Engineer, Mixing

2001 True Colors Learning Channel Engineer, Mixing

2005 The Cultivated Life: Thomas Jefferson & Wine Madison Film, Inc. Engineer

Film Credits/DVD

Year Film Producer/Company Role

1998 A Stranger In the Kingdom Kingdom County Productions Engineer, Mixing

2002 The Year That Trembled Kingdom County Productions Engineer, Mixing

2012 Performing The Score Malcolm Bilson /Liz Field Engineer, Mixer, Post Production

supervisor

Live Recordings

2000 – present:

Adam Day, Amy Glicklich, Atomic Forces, Aurelio Martinez, Avett Brothers, Bad Dog, Dalfa Toujours, Ballake Sissoko, Bamboleo, Ben Suchy, Big Leg Emma, Black Castle, Blackfire, Bobbie Henrie & the Goners, Boubacar Traore, Boy With A Fish, Bubba George, Buvas, Calico Moon, Campbell Brothers, Cary Fridley, Cherish the Ladies, Christina Ortega, Cletus & the Burners, Crow Greenspun, Cypher:Dissident, Cyro Baptista & Beat the Donkey, D’Gary, December Wind, Donna the Buffalo, John Anderson, John Brown’s Body, John Specker, Johnny Donegan, Johnny Dowd, Jones Benally&American Indian Dance Troupe, Joules Graves, J-San & the Analogue Sons, Kanenhio Singers, Kathy Ziegler, Keith Franks & the Soileau Zydeco Band, Kekele, Kusun Ensemble, Life, Little Egypt, Lonesome Sisters, Los Lobos, Los Pochos, Lunasa, Mamadou Diabate, Mary Lorson & Saint Low, Mecca Bodega, Michael Franti & Spearhead, Miche Fambro, Minnies, Moochers, Moontee Sinquah, Musafir, Nedy Arevalo, Oculus, Old Crow Medicine Show, Squirrels, Paso Fino, Patty Loveless, Perfect Thyroid, Plastic Nebraska, Preston Frank & His Zydeco Family Band, Project Matsana, Ramatou Diakate, Randy Whitt & the Grits, Red Hots,

Red Stick Ramblers, Revision, Rickie Lee Jones, Ritsu Katsumata, Rockridge Brothers, Rodney’s Nigh, Rokia Traore, Ronnie Bowman and the Committee Rusted Roof, Samite, Scotty Campbell & Zydeco Experiment, Shane & Diana, Sillanpaa Family, Sim Redmon Band, Slo-Mo, Snake Oil Medicine Show, Solas, Son de Madero, Steve Riley & the Mamou Playboys, Sujata Sidhu, Sunny Weather, Susana Baca, The Believers, The Blue Rags, The Burren, The Buvas, The Campbell Brothers, The Del McCoury Band, The Duhks, The Fierce Guys, The Flying Clouds, The Hix, The Horse Flies, The Lonesome Sisters, The

Mahotella Queens, The Meditations, The Overtakers, The Red Hots, The Splendors, The Super Rail Band, The Sutras, The Thins, Thomas Mapfumo, Thousands of One, Ti Ti Chickapea, Tonemah, Trevor MacDonald, Walter Mouton & the Scott Playboys, Wingnut, Yo Mama’s Big Fat Booty, Zydeco Experiment.

# # #

http://www.pyramidsoundstudios.com/

Contacts:

Alex Perialas, Pyramid Sound

Phone: 607.273.3931

Email: alex@pyramidsoundstudios.com

Andy Adelewitz, PR consultant

Phone: 607.257.0455

Email: andy@adelewitz.com

Original source.

No Comments In a time of just about any style being called “black metal” if someone shrieks during the recording, Sammath stay true to the older ideal of powerful, melancholic, evil and naturalistic music.

In a time of just about any style being called “black metal” if someone shrieks during the recording, Sammath stay true to the older ideal of powerful, melancholic, evil and naturalistic music. http://soundcloud.com/centurymediarecords/massacre-succumb-to-rapture

http://soundcloud.com/centurymediarecords/massacre-succumb-to-rapture

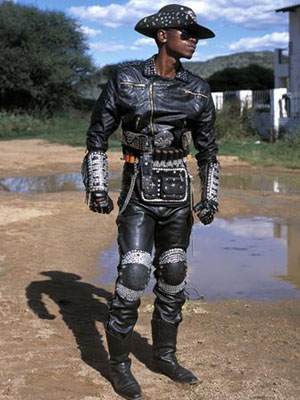

While Botswana is perhaps best known for its wildlife reserves, a burgeoning counter-culture is painting a very different image of the small south African country.

While Botswana is perhaps best known for its wildlife reserves, a burgeoning counter-culture is painting a very different image of the small south African country.

People love to talk about music. A story about Ken Caillat’s new book covering the inside story behind the Fleetwood Mac album, “Rumours,” had several readers gushing about their own favorite albums. Seems there are all kinds of “perfect albums” for all kinds of tastes.

People love to talk about music. A story about Ken Caillat’s new book covering the inside story behind the Fleetwood Mac album, “Rumours,” had several readers gushing about their own favorite albums. Seems there are all kinds of “perfect albums” for all kinds of tastes. Contacts: Alex Perialas, Pyramid Sound Andy Adelewitz, PR consultant

Contacts: Alex Perialas, Pyramid Sound Andy Adelewitz, PR consultant