http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EdjS4qMXQmQ

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sNwfRGLOWtc

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PNMoJiPBVkI

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NbGqPRFyHtg

5 CommentsTags: slayer

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EdjS4qMXQmQ

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sNwfRGLOWtc

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PNMoJiPBVkI

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NbGqPRFyHtg

5 CommentsTags: slayer

Singaporean war/terror metal band Impiety recently announced a new mini-album, The Impious Crusades, and now reveal that the slab of screaming death will hit your mailbox on August 6th, 2013, as released by Hell’s Headbangers Records.

Singaporean war/terror metal band Impiety recently announced a new mini-album, The Impious Crusades, and now reveal that the slab of screaming death will hit your mailbox on August 6th, 2013, as released by Hell’s Headbangers Records.

According to frontman Shyaithan, “Mission accomplished, and honestly really satisfied with how this record turned out! The Impious Crusade is a giant leap ahead from the last Impiety album, and to top this one is going to be severely difficult. But that is what I enjoy most, and shall continue to further challenge myself pushing wider, deeper, and even further beyond boundaries of untamed death and chaos.”

The Impious Crusades unites itself on the Impiety motto of “crush, kill destroy” and includes a cover of Sorcery’s “Lucifer’s Legions” and artwork by cult paintbrush Lord Sickness. Although the band have released no information about style, it now seems it will be coherent with their past years of blasting, racing, raging and deconstructive fast simple death metal with undertones of melody.

Although self-referential titles are generally harbingers of poor quality releases, the band seems united on this mini-album as a kind of short and quick mission statement, which could lead to a summation of past works into a single hard-hitting dose. Fans await this exciting release as the band makes the tracklist available:

1. Arrival of the Assassins

2. Commanding Death & Destroy

3. Accelerate the Annhiliation

4. The Impious Crusade

5. Lucifer’s Legions (Sorcery Cover)

Classic Florida progressive death metal band Nocturnus, famous for spidery riffs interlaced with outer space keyboards, dominated the metal world’s appetite for bizarre and uncompromising music back in the 1990s, but their music is now out of print.

Classic Florida progressive death metal band Nocturnus, famous for spidery riffs interlaced with outer space keyboards, dominated the metal world’s appetite for bizarre and uncompromising music back in the 1990s, but their music is now out of print.

Their label, Earache Records, wants to re-issue the Nocturnus classic Thresholds, but there’s a catch: the fans have to pay for it in advance. Unlike the usual underground pre-orders, where individual fans order the album and when there’s enough cash the label takes it to print, Earache is using a Kickstarter page to launch the funding request.

If demand is met, Thresholds will be pressed on 100 clear, 200 green, 300 purple and 400 black LPs with the recording taken from the original DAT master. For more information, visit the Nocturnus Thresholds re-issue Kickstarter page.

12 Comments DeathMetal.org continues its exploration of radio with a podcast of death metal, dark ambient and fragments of literature. This format allows all of us to see the music we enjoy in the context of the ideas which inspired it.

DeathMetal.org continues its exploration of radio with a podcast of death metal, dark ambient and fragments of literature. This format allows all of us to see the music we enjoy in the context of the ideas which inspired it.

Clandestine DJ Rob Jones brings you the esoteric undercurrents of doom metal, death metal and black metal in a show that also exports its philosophical examinations of life, existence and nothingness.

This niche radio show exists to glorify the best of metal, with an emphasis on newer material but not a limitation of it, which means that you will often hear new possibilities in the past as well as the present.

If you miss the days when death metal was a Wild West that kept itself weird, paranoid and uncivilized, you will appreciate this detour outside of acceptable society into the thoughts most people fear in the small hours of the night.

The playlist for this week’s show is:

Without a doubt the Internet has been the great communications revolution of our time, changing the shape and the pace of commerce and culture alike.

For metal, the internet has primarily meant a far wider audience-reach, enabling the growth of the larger labels and festivals into massive unit-shifters, and allowing even the feeblest of bedroom bands to find five minutes of someone’s attention.

High speed downloading has made metal music across the board more heavily pirated than ever, yet simultaneously given the whole genre far more exposure than before.

Perhaps most significantly, the ability it gives individuals to both broadcast and share content has allowed forgotten bands – who, for the quality of their work, should have been classics – to reach audiences and acclaim they previously missed out on.

The internet, like society itself, however is not one great monolithic thing, but simply a series of networks, meeting points and exchanges, always changing and adapting piecemeal to developments in both technology and culture, and in-turn shaping the society it forms part of.

Where in the early years of the internet small localized networks allowed for basic communication and facilitated real world interaction, the present-day internet has through its size, speed and centralization become like an immersive parallel world, spawning its own cultural and even linguistic tropes; substituting in many ways for tangible real world interaction.

Three years ago Wired magazine actually pronounced the death of the world wide web, noting that after hitting a peak around the year 2000 the number of sites we visit and ways that we access them has become narrower and narrower. Sites like Facebook, Google and Wikipedia have an increasingly dominant share of global traffic, in the process marginalizing independent sites and narrowing both the kinds of information we receive and how we consume it. This is not necessarily a straight battle between the evil-empire corporations and the idyllic small world everyman (in the way that some activists like to portray politics in general), but a trade off between different advantages and disadvantages.

Fewer sites means greater efficiency and organisation with which content can be managed and shared, and also ups the standard for site design, development and security. The downside is that it enforces a steady uniformity on both the way in which things are communicated and on the prominence they are able to take. No one thing any longer can particular amount to more than the same little square box of information that makes up any search engine result or item on a social network feed, and everything comes and goes as quickly as anything else does in the same continuous stream.

Also, perhaps counter-intuitively, it puts an increasing amount of power in the hands of ‘the community’ in the most amorphous and anonymous sense. Facebook for example, beyond a few specific algorithms, is far too big for those that run it to police the content everyone posts on it, so it relies on its users to flag antisocial content and determine what should be shut down. Obviously such a system is hypothetically open to exploitation from particular groups, but above all it enforces a status quo line of thinking on what is to be considered legitimate or acceptable information.

So the internet as it currently exists has helped put limits on both what we say and how we say it.

Metal music before the growth of the internet had been a largely underground cultural phenomena: specifically spurning group-think methods of quality-control and organizing more along Darwinian/Nietzschean lines, wherein the strength and boldness of the music determined its ascension to and effectively perpetual status.

The growth of the internet has therefore sometimes jarringly co-existed with metal. Early hessian websites like the Dark Legions Archive and the BNR Metal Pages set the tone for metal on the internet as it had existed in the real world up until then: an enthusiast-centered mixture of devotion, and unsparing praise for bands and albums whose quality made them deserving. Newer and essentially more democratic net developments however harbor a conflict between those who represent the old ways, and those used to the confused standards, egalitarian platitudes and big media saturation that characterize metal in its later years.

The democratization facilitated by the internet hasn’t so far created a widespread resurgence in quality. The re-exposure of forgotten musical gems and past scenes has not so much led to a revival of the spirit that went with those bands, as much as it has contributed to the stagnating plurality of lifestyle options and consumerist flavors offered by our crumbling utopia. For example, the growth of retro-thrash, complete with authentic caps, sneakers, d-beats, nuclear-themed artwork and Anthrax-style vocals – or the retro Swedish style bands, all playing roughly the same bouncy down-tuned death metal through a boss hm2. Outwardly they ape the sound of the genuine article, but beneath the surface offer little of substance, never really aspiring to do more than just reproduce the appearance of those older experiences. Fundamentally this is no different than the obvious and easily called-out hipster cult – that fetishizes the random ephemera of past fads for the sole aim of shallow self-aggrandizement. The retro-thrashers and their like are metal’s own version of hipsters – products of the dead end civilization, endlessly and emptily regurgitating its own past for lack of any meaningful inner direction.

In this respect, the internet has only heightened the dopamine-addicted individualism of the consumer society and absorbed metal into that; allowing more of us to wall ourselves off inside our own heads – where we can play out whatever inconsequential fantasy we feel like and make affectations of action and authenticity without actually living it.

For those who know how to use it – and are cautious enough to keep its negative effects at arm’s length – the internet can be an invaluable resource for both sharing ideas and educating oneself. Metal on the internet need not be any different. Enough great music, previously under the radar, can (and has) come to light because of the internet to justify its utility. And, provided you are smart about it, it can also be an effective promotional tool for quality metal and for higher standards; as long as, above all else, you are careful not to get sucked into treating it as the ego feedback loop that most people use it for.

Tags: podcast

Arthur Schopenhauer once wrote that there were three kinds of authors: those who write without thinking, those who think as they write, and those who write only because they have thought something and wish to pass it along.

Arthur Schopenhauer once wrote that there were three kinds of authors: those who write without thinking, those who think as they write, and those who write only because they have thought something and wish to pass it along.

Similarly, it is not hard to produce a decent heavy metal album. You cannot do it without thinking, but if you think while you go, you can stitch those riffs together and make a plausible effort that will delight the squealing masses.

But to produce an excellent heavy metal album is a great challenge. It’s also difficult to discuss, since if you ask 100 hessians for their list of excellent metal albums, you may well get 101 different answers. Still, all of us acknowledge that some albums rise above the rest.

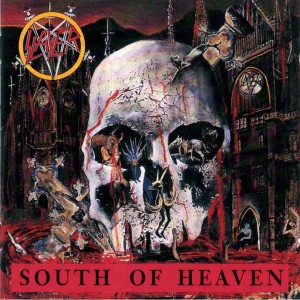

South of Heaven is to my mind such an album because it hits on all levels. Crushing riffs: check. Intense abstract structures: check. Overall feeling of darkness, power, evil, foreboding and all the things forbidden in daylight society: check. But also: a pure enigmatic sublime sense of purpose, of an order beneath the skin of things, resulting in a mind-blowing expansion of perspective? That, too.

Slayer knew they’d hit the ball out of the park with Reign in Blood. That album single-handedly defined what the next generations of metal would shoot for. It also defined for many of us the high-water mark for metal, aesthetically. Any album that wanted to be metal should shoot for the same intensity of “Angel of Death” or “Raining Blood.” It forever raised the bar in terms of technique and overall impact. Music could never back down from that peak.

However, the fertile minds in Slayer did not want to imitate themselves and repeat the past. Instead, they wanted to find out what came next. The answer was to add depth to the intensity: to add melody — the holy grail of metal has since been how to make something with the intensity of Reign in Blood but the melodic power of Don’t Break the Oath — and flesh out the sound, to use more variation in tempo, to add depth of subject matter and to make an album that was more mystical than mechanical.

Only two years later, South of Heaven did exactly that. Many fans thought they wanted Reign in Blood: The Sequel (Return to the Angel of Death) but found out that actually, they liked the change. Where Reign in Blood was an unrelenting assault by enraged demons, South of Heaven was the dark forces who infiltrated your neighborhood at night, and in the morning looked just like everyone else. It was an album that found horror lurking behind normalcy, twisted sadistic power games behind politics, and the sense of a society not off course just in politics, economics, etc. but having gone down a bad path. Having sold it soul to Satan, in other words.

The depth of despair and foreboding terror found in this album was probably more than most of us could handle at the time. 1988 was after all the peak of the Cold War, shortly before the other side collapsed, but Slayer wasn’t talking about the Cold War. For them, the problem was deeper; it was within, and it resulted from our acceptance of some kind of illusion as a force of good, when really it concealed the lurking face of evil. This gave the album a depth and terror that none have touched since. It is wholly unsettling.

Musically, advancements came aplenty. Slayer detached themselves from the rock formula entirely, using chromatic riffs to great effectiveness and relegating key changes to a mode of layering riffs. Although it was simpler and more repetitive, South of Heaven was also more hypnotic as it merged subliminal rhythms with melodies that sounded like fragments of the past. The result was more like atmospheric or ambient music, and it swallowed up the listener and brought them into an entirely different world.

South of Heaven was also the last “mythological” album from Slayer. Following the example of Black Sabbath’s “War Pigs,” Slayer’s previous lyrics found metaphysical and occult reasons for humanity’s failures, but never let us off the hook. Bad decisions beget bad results in the Slayer worldview, and those who are happiest with it are the forces of evil who mislead us and enjoy our folly, as in “Satan laughing spreads his wings” or even “Satan laughs as you eternally rot.” The lyrics to “South of Heaven” could have come from the book of Revelations, with their portrayal of a culture and society given to lusts and wickedness, collapsing from within. (Three years later, Bathory made the Wagnerian counterpoint to this with “Twilight of the Gods.” Read the two lyrics together — it’s quite influential.)

Most of all, South of Heaven was a step forward as momentous as Reign in Blood for all future metal. We can create raw intensity, it said, but we need also to find heaviness in the implications of things. In the actions we take and their certain results. In the results of a lack of attention to even simple things, like where we throw our trash and how honest we are with each other. That is a message so profoundly subversive and all-encompassing that it is terrifying. Basically, you are never off the hook; you are always on watch, because your future depends on it.

Slayer awoke in many of us a sense beyond the immediate. We were accustomed to songs that told us about personal struggles, desires and goals. But what about looking at life through the lens of history? Or even the qualitative implications of our acts? Like Romantic poetry, Slayer was a looking glass into the ancient ruins of Greece and Rome, onto the battlefields of Verdun and Stalingrad, and even more, into our own souls. Reign in Blood broke popular music free from its sense of being “protest music” or “individualistic” and showed us a wider world. South of Heaven showed us we are the decisionmakers of this world, and without our constant attention, it will burn like hell itself.

I remember from back in the day how many of my friends were afraid of South of Heaven. The first two Slayer albums could be fun; Reign in Blood was just pure intensity; South of Heaven was awake at 3 a.m. and existentially confused, fearing death and insignificance, Nietzschean “fear and trembling” style music. It unnerved me then and it does still today, but I believe every note of it is an accurate reflection of reality, and of the charge to us to make right decisions instead of convenient ones. And now with Slayer gone, we have to compel ourselves to walk this path — alone.

13 CommentsTags: goat, slayer, south of heaven

And so, after a long time of thinking he was immortal, we have to say goodbye to Jeff Hanneman and hope that all the doubters are wrong and there’s some metal Valhalla where he’s drinking Heineken and exploring all those solos that he did not have the energy on earth to discover.

And so, after a long time of thinking he was immortal, we have to say goodbye to Jeff Hanneman and hope that all the doubters are wrong and there’s some metal Valhalla where he’s drinking Heineken and exploring all those solos that he did not have the energy on earth to discover.

In the traditions from which I come, the way we handle death — which we handle badly, if at all — is to describe the meaning of the life. This enables us to get away from the person, who is either nothingness or eternity per the rules of logic, and instead look at what they fought for.

In other words, what drove them to engage with life and reach out every day, which are things most people don’t do. Most of us just “attend” to things, like jobs and families, and hope for the best. The giants among us are driven onward by some belief in something larger than themselves or than the social group at large. They are animated by ideas.

For Jeff Hanneman, the idea was both musical and a vision of what that music should represent. He peered into the dystopia of modern times with one eye in the anarchistic zone of the punks, and the other in the swords ‘n’ sorcery vision of a metalhead. When he put the two together, he came up with something that makes Blade Runner and Neuromancer seem gentle.

Having seen this, he came back.

“I have seen the darkened depths of Hell,” the chorus begins. For Hanneman, his sin was too much sight. He saw the failings of his present time, like a punk; he saw how this fit into the broader concept of history, like a metalhead. Putting the two together, he saw darkness on the horizon encroaching and assimilating all it touched.

To fight back, he created music for people such as himself, youth adrift among the ruins of a dying empire. He created music that made people not only want to accept the darkness, but to get in there and fight. Not fight back necessarily, but fight to survive. He helped us peel away social pretense and reveal our inner animals which have no pretense about predation and self-defense, unlike civilized people. Hanneman prepared us for the time after society, politeness and rule of law fail.

This was, in addition to the shredding tunes, his gift to the world: a vision of ourselves continuing when all that we previously relied on has ended. Like all visionaries, he was before his time, and like many, did not live to see his vision realized. However, for millions of us, he gave us hope.

It is also worth noting that Slayer renovated heavy metal in such a way to set its highest standard. In any age, Reign in Blood, South of Heaven and Hell Awaits will be a high point for a genre. They fought back against the tendency of metal to become more like the rock ‘n’ roll on the radio, and to lose its unique and entirely different soul. Hanneman and his team pushed forward the frontier for metal, and pushed back the assimilation by rock music.

In the wake of Hanneman’s death, we are without a king, so to speak. The elder statesman role passes to a new generation, and they must find in their souls the bravery and fury to create much as Jeff Hanneman did, a standard and a culture based in a vision that surpasses what everyone else is slopping through. We are poorer for the loss of Jeff Hanneman, but our best response is to redouble his efforts, and push ourselves forward toward a goal he would respect.

18 CommentsTags: assimilation, death metal, Heavy Metal, slayer, Speed Metal

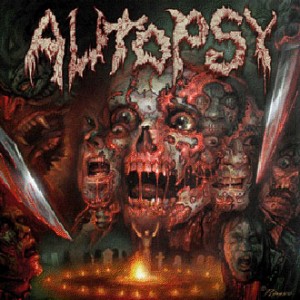

Autopsy returns to death metal on July 2, 2013, with a new full-length album entitled The Headless Ritual.

Autopsy returns to death metal on July 2, 2013, with a new full-length album entitled The Headless Ritual.

Famed for their contributions to late-1980s death metal and its continued guidance through the 1990s, Autopsy arose as a band playing a chaotic, filthy, organic sounding form of death metal, which was in contrast to the more rigidly technical “Morbid Angel” inspired bands of the day. In many ways, Autopsy was a bridge between the more structured death metal and the more chaotic but more melodic bands from the grindcore world like Carcass and Bolt Thrower.

Fresh from the studio, Chris Reifert (drums) was able to give us a few words on the nature of the new album, its style and the future for Autopsy.

You’re in the process of recording The Headless Ritual. How do you see this album as continuing and differing from your previous works?

Actually it’s complete and we’re just waiting for it to come out at this point. Musically and lyrically it’s pretty much Autopsy. No major changes, but no rehashing of old ideas either. It’s a big nasty chunk of death metal, simply put.

Will you be using the same production as previous albums for The Headless Ritual? Can you tell us how it sounds so far? Will it be more punk-influenced, or more metal-influenced, than Macabre Eternal?

We went with the same method of recording as we always have, but this one sounds a bit bigger than Macabre Eternal, I dare say. And again, it sounds like Autopsy. There’s fast stuff, slow stuff and all the weird stuff in between.

Thanks, Chris!

At deathmetal.org, we’re naturally looking forward to the new Autopsy. Not only is it another of metal’s legends come back to life in the post-2009 old school metal revival, but it’s also a personal favorite that we believe has potential to revive the intensity of death metal.

Furthermore, this album also promises to bring back the thoughtful and the odd that defined the genre so much during its early days. It was a frontier then and the frontier may be re-opening now. As Chris says, “There’s fast stuff, slow stuff and all the weird stuff in between.” This is a welcome break from the all-ahead-go clones that have made death metal seem one dimensional.

The Headless Ritual will show us Autopsy at the peak of their ability and returning in fine form and fine spirits, as these answers show us. Thanks to Brian Rocha at Fresno Media for his help with this mini-interview!

5 CommentsTags: autopsy, death metal

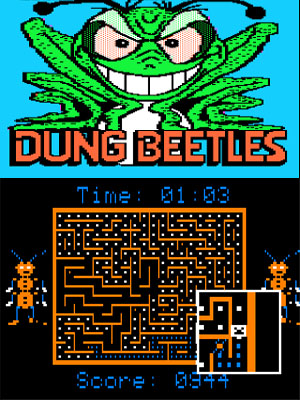

The University of Montreal in Quebec presented a conference on the cultural, aesthetic and historical hybridizations between video games on heavy metal. The presentations, occurring on March 15th, are available via video at the bottom of this post.

The University of Montreal in Quebec presented a conference on the cultural, aesthetic and historical hybridizations between video games on heavy metal. The presentations, occurring on March 15th, are available via video at the bottom of this post.

Although the conference was presented in French, the video is fully captioned in English. Professors Dominic Arsenault and Louis-Martin Guay presented their research as the cornerstone of the conference, covering the origins of their interest in the topic and some of its history.

That history moves us through the arcade era from pinball machines to stand-alone video games, then takes us through the home gaming revolution with 8-bit machines, and finally to 16-bit gaming and now modern game as technology evolved and became cheaper. It compares the music, imagery and traditions of both metal and video game cultures.

At the peak of this is Professor Arsenault’s attempt to meld metal and classic gaming, covering “experimentations in transfictionality, sound design and concept for 8-bit metal that’s not just metal covers, 8-bit covers, game-themed metal or chiptunes.” Arsenault, who believes metal and video games are a natural fit, has presented related research at other conferences to great success.

Our two cents here is that metal and video games arose almost in parallel and both emphasized the solitary youth whose parents, fractured by divorce and social chaos, withdrew in an age of nuclear terror. As a result, both genres tend to focus on conceptual settings that emphasize both escapism, and a tackling in this new escapist context of ideas that threaten the solitary adventurer in real life. By placing those threatening ideas in an otherworldly context, they can be addressed as removed from their painful (and boring) day-to-day reality.

13 CommentsTags: academia, Heavy Metal, nuclear war, videogames

Part of our job as people who support and believe in metal is to cheer its adoption in the world. However, as part of that mission, we want to make sure the task is done correctly. After all, McDonald’s “Black Metal Happy Meals” wouldn’t exactly be the direction we wanted to go in, would they? Nor would an article that argued heavy metal was a form of protest music or the continuation of disco (actually, that’s dubstep).

Part of our job as people who support and believe in metal is to cheer its adoption in the world. However, as part of that mission, we want to make sure the task is done correctly. After all, McDonald’s “Black Metal Happy Meals” wouldn’t exactly be the direction we wanted to go in, would they? Nor would an article that argued heavy metal was a form of protest music or the continuation of disco (actually, that’s dubstep).

Thus we turn to Nottingham University’s new “heavy metal” undergraduate degree, which allows you to spend your college years learning music performance, composition, marketing and songwriting as you go through your degree program. On the surface, this is a great thing, in that it gives heavy metal some recognition in academia as a type of discipline. Or is it?

It seems to us that the approach followed by other metal academics is more sensible, which integrates heavy metal into fields like English literature, sociology, history, philosophy and linguistics. Instead of making metal an isolated commercial product, and teaching it in the same facility that because it teaches a rock-based curriculum will most likely teach a metal-flavored version of rock, the metal academics prefer to pursue metal on the graduate level.

While we applaud Nottingham University for being open to the idea of heavy metal in academia, we suggest a different approach. Metal is not a product, but the result of a thought process, which is the only way to unite such decentralized compositional elements into a singular concept. Thus the best use of the undergraduate degree is perhaps to study the background ideas that are needed to make sense of it…

No CommentsTags: academia, Heavy Metal