Bands, labels and artists… we need to have a little talk about YouTube. Specifically, the absence of your official and legitimate releases on YouTube uploaded by you so that royalties go to the bands.

Like many of us, I work in an office. There are many like it, but this one is mine. I have a computer where I am expected to do work. But who is fooled? Most “work” gets done in a few hours in the morning, and the rest of the day is dodging meetings and doing paperwork.

While I have this sort of expensive computer, fat internet access, and these nice Harmon/Kardon speakers, I like to put all this high technology to use as a $4 radio. A $4 radio where I can choose what the DJ plays.

I use YouTube to find music, like many others. The reason is simple: almost no workplaces filter YouTube, and no evidence is left behind. I am not keeping pirated music on my computer and I am not pirating music. I am watching videos. True, these videos seem to feature only the cover image of an album while music (just coincidentally from that album) plays. But nonetheless, technicallyTM they are videos.

Many of you do the same.

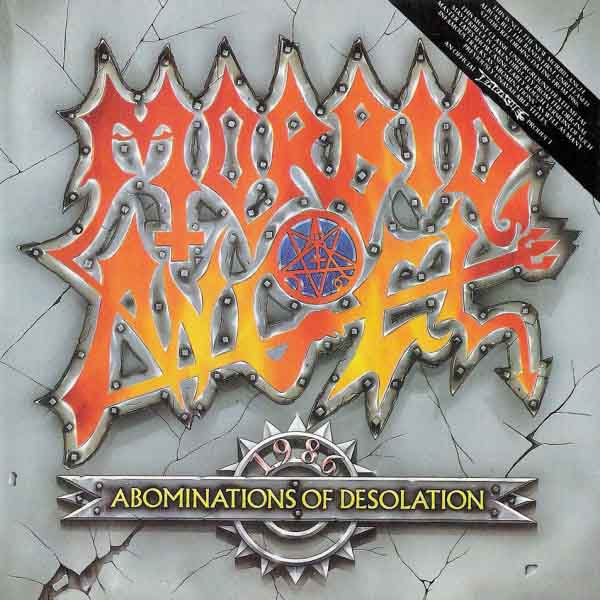

I have a problem with this situation. When I want to check out, say, an early death metal classic, I type it in the search blank on YouTube. Then a video comes up. But it does not belong to the band, the label, the musicians, their family, dogs or friends. It belongs to some random guy named “BronyThugLife69” from Hoboken.

Why does this matter? As I type this email, the Deicide video I am enjoying has 132,068 views. At the royalty rate that YouTube pays, which is about 1/10 of a cent per play, that means BronyThugLife69 has earned over a thousand dollars for this video. He’s making bank for the simple act of pasting a cover image onto an MP3, uploading it to YouTube and not getting busted.

Now I click on BronyThugLife69’s profile. Oh look — he has not ten, not a hundred, but a thousand videos. It takes about five minutes to paste ten MP3s and a cover image into a video creation program, save to WMV, and upload to YouTube. If only a hundred people click on each of his videos per month, he’s making a professional salary.

Now, you may ask, why do I not simply upload my own versions of my favorite bands?

Unlike BronyThugLife69, I do not want to make money from someone else’s work. This band wrote the music, got a record contract, recorded the album, promoted it and toured on it. They deserve the money. I could always upload videos without receiving compensation, but that is a boring hobby and I get nothing from it.

Since YouTube is unlikely to go away in the near future, people like me will continue to use it. Bands and labels should, instead of blowing off this opportunity, upload their own albums and make sure the checks go to the band. If they are too lazy to do this, I will do it for them for a royalty of ten percent of their royalties.

This is not difficult. People will listen to your music either way. You can take it down, but that requires constant vigilance because someone else will in turn upload the missing Deicide video. If the band uploads it, the cash goes directly to them.

Is YouTube piracy? Probably, but not really. Most of us are checking out new music or listening to favorites we own back at home. We don’t care that the sound quality is not good. Most will use earphones, or these tiny desktop speakers, because we are in noisy environments or quiet ones and we have to hide the evil devil metal we are enjoying from our coworkers who might exorcise and eviscerate us if they knew.

If you bands and labels could get your act together and upload your own stuff, you would enable me to enjoy guilt-free listening to classics while I file these TPS reports. Me, and millions of other faceless workers at anonymous jobs in generic companies across the world, would really appreciate it.

15 Comments