Article by David Rosales.

I. A Romantic Art

In the past, we have likened the spirit of metal that culminates in death and black metal to that of the literary, romantic movement in Europe. Romanticism was meant to embody ideals of naturalism and individualism in a return to primeval spirituality connecting us with our origins, our surroundings, and a more conscious future. The romantic character of the 19th century stands in glaring opposition to the heavy industrialist upsurge and man-centered utilitarianism of that time. Epitomized metal contrasts with this idea in one important aspect: while artists two centuries ago strived to bring attention to the importance of human subjectivity, underground metal stressed irrelevance of the human vantage point.

In describing metal as a neo-romantic artform we may well be undermining the aspects that define it in its historical and psychological contexts. Historical as each movement is encased in a flow of events linked by causality and psychological, on the other hand because of the relative independence and unpredictability with which leading individuals affront these inevitable developments. Together, these two factors account for freedom of choice within predestination. Even though romanticism and metal were both reactions to the same decadence at different points in time, the latter rejects the former’s inclination towards universal human rights and other products of higher civilization in exchange for a nihilistic realism arising from the laws of nature. Underground metal is a detached representation of a Dark Age; one where power and violence are the rule in which all forms of humanism are hopelessly deluded or simply hypocritical.

The uncontrolled and contrarian character of metal stands at odds with the more self-aware and progressive bent of romanticism. Metal, at least in its purest incarnations, can never be assimilated – something that cannot be said of the older art movement. Pathetic attempts at dragging metal under the mainstream umbrella that abides by status quo ideals often fail catastrophically. When forcefully drawn out before dawn’s break it will inevitably miserably perish upon contact with the sun’s rays like a creature of catacombs and dark night-forests.

Attempting to define metal is as elusive as trying to pinpoint ‘magic’. Outsiders cannot even begin to recognize its boundaries. The mystical, ungraspable, and intuitive nature it possesses attests to this and sets it apart from romanticism in that not even those belonging to it are able to crystallize a proper description. The very substance of the genre is felt everywhere but the innermost sanctum always dissipates under the gaze of the mind’s eye.

II. Romantic Anti-Modernism

Even though it cannot be said that the one defines or encompasses the other, the connection between romanticism and metal nevertheless exists. Aside from the concrete musical link between them which helps us describe metal as a minimalist and electronic romantic art, the abstract connection is more tenuous and related to cyclic recurrence1. Metal is not a revival of romanticism nor its evolution, but perhaps something more akin to its rebellious disciple: a romantic anti-modernism.

The foundation of this anti-modernism is a Nietzschean nihilism standing in stark contrast with hypocritical modernist dogma; it spits in the face of the semantic stupidity of post-modernism. This is a sensible and ever-searching nihilism2 that does not attach itself to a particular point of view but parts from a point of disbelief in any authority. It is a scientific and mystic nihilism for those who can understand this juxtaposition of terms. It does not specialize in what is known as critical thinking but in the empirical openness to possibilities taken with a grain of salt. The first dismisses anything that does not conform to its rigid schemata; the second one allows relativism as a tool with the intention of having subjective views float around while transcending all of them and moving towards unattainable objectivity.

Such transcendentalism connects metal with Plato and Theodoric the Great rather than with Aristotle and Marcus Aurelius. Metal looks beyond modern illusions of so-called freedom and the pleasure-based seeking of happiness. It recognizes that without struggle there can be no treasure and that today’s perennial slack will only lead to complacent self-annihilation. This is why, instead of representing the blossoming of nature in man through the sentimentalisms of romanticism in its attitude above time, to use the words of a wise woman, metal stands stoutly as a form of art against time.

III. Essential Reading for the Metal Nihilist

As an attempt to communicate our understanding of the essence and spirit of underground metal, below are some books through which to start the abstract journey through metal and the metaphysics that moves it.

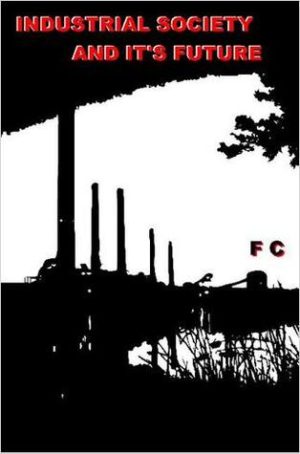

Theodore John Kaczynski – Industrial Society and Its Future

Albert Mudrian – Choosing Death: The Improbable History of Death Metal and Grindcore

Homer – The Illiad

The Bhagavad Gita

J.R.R. Tolkein – The Children of Húrin

Immanuel Kant – Critique of Pure Reason

IV. Some Music Recommendations for the Metal Nihilist

We have traditionally presented a certain pantheon of underground death and black metal to which most readers can be redirected at any moment. A different set is presented below that is nonetheless consistent with the writer’s interpretation of Death Metal Underground’s vision.

Esa-Pekka Salonen – Bruckner: Symphony No. 4 in E-Flat Major “Romantic“

Sammath – Godless Arrogance

Cóndor – Nadia

Bulgarian State Radio & Television Female Vocal Choir – Le Mystère des Voix Bulgares

Julian Bream – La Guitarra Barroca

Timeghoul – 1992-1994 Discography

Iron Maiden – Somewhere in Time

Bathory – Twilight of the Gods

V. Films

Not being a connoisseur of cinema in general, the following is but a friendly gesture. This is a loose collection for the transmission of a basic underground metal pathos.

Tous les Matins du Monde

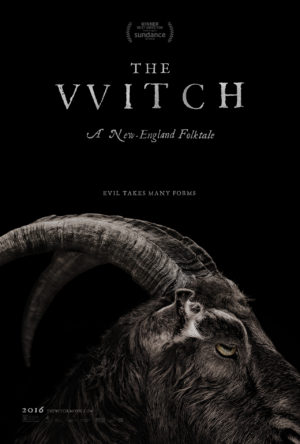

The Witch: A New-England Folktale

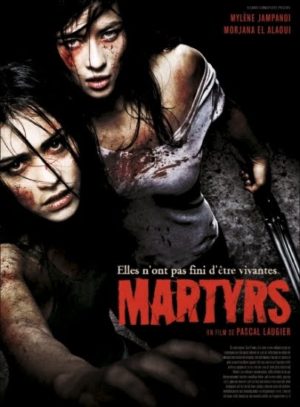

Martyrs

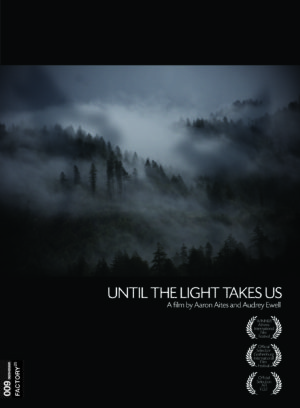

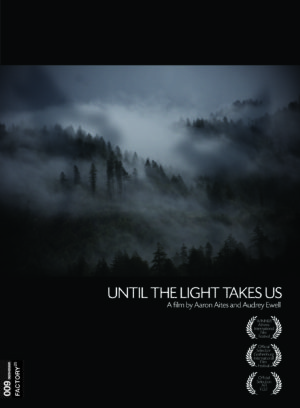

Until the Light Takes Us

A 2008 documentary film by Aaron Aites

and Audrey Ewellabout the early 90s

black metal scene in Norway.

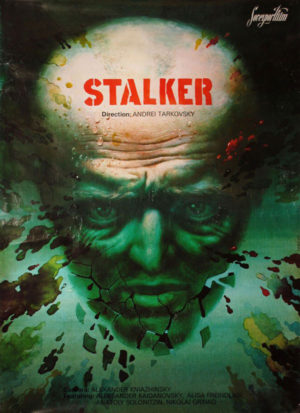

Andrei Tarkovsky – Stalker

Notes

1This is not the re-happening of the exact same universe that Nietzsche is supposed to have been talking about, but a transcendental recurrence of sorts. What I am trying to express here is the cyclic reappearance of abstract and collective concepts among humans, because they are also part of this universe and as such are subject to such underlying pendulum swings in the forces that move it. Perhaps a better descriptor could have been abstract collective concept reincarnation, but that seemed to convoluted, and cyclic recurrence captures the wider phenomenon, irrespective of what definition academia wants to adhere to.

2This somewhat liberal use of the term nihilism deserves to be explained a little further in order to avoid confusion. By this it is not meant that metal’s outlook consists of nihilism in the ultra-pessimistic sense, in the sense of total defeat, which seems to be the expectancy of most people from nihilism. The idea here is that as an art movement born in the post-modern era, in a civilization that has already been ravaged by nihilism, stripped from relevant cults, metal begins from a posture of extreme skepticism that is extended to everything and everyone. This skepticism is nihilistic because no intrinsic value is placed on anything, yet it is scientific because it is curious and will experiment. Metal’s development dances between nihilism and individualistic transcendentalism.

67 CommentsTags: aaron aites, albert mudrian, Andrei Tarkovsky, anti-modernism, anton bruckner, Bathory, Bhagavad Gita, condor, friedrich nietzsche, Godless Arrogance, Homer, iron maiden, j.r.r. tolkien, julian bream, Kant, modern metal, modernism, Nadia, Nihilism, Philosophy, plato, Romanticism, sammath, somewhere in time, Stalker, Ted Kaczynski, The Illiad, timeghoul, tolkein, twilight of the gods, until the light takes us