I. Music for the sake of…

In Book I of Plato’s The Republic, Socrates is engaged in an exchange of ideas with Thrasymachus regarding the nature of justice. In this debate, Thrasymachus is noticeably anxious to drive a point that justifies his views rather than finding out the truth. In between the sarcastic remarks and false humility that characterize Socrates, the older philosopher puts forward questions and comparisons that shed light on the topic in interesting angles.

One of the most interesting arguments came after Socrates’ opponent declared that justice could be defined as “the interest of the stronger”. Socrates’ response came to a point where he postulated that all art (which he uses as an equivalent to “talent” or “occupation”) acts rather in the interest of the receiver of his work. So the true art of the physician is neither in the receiving of money nor in a perfection of medicine in itself, but in the curing of maladies and keeping the body healthy.

Socrates then extrapolated this to illustrate how justice was what a ruler imparted in the interest of the people. A ruler is given power to lead and impart justice to the best interest of the people they govern. That rulers may often become corrupt is a different matter.

This got me thinking, what about music? What is the purpose of music? What is music for? From history, we know music has served different roles, from religious expression, conducive to a form of indoctrination, to aristocratic caprice, to romantic ideology, nationalist propaganda and every other conceivable use of music as ambiance or a vehicle for anything else.

We should make it clear that not only were these approaches different, but not all were equally close to the truth about music. Most do not understand that it can only evoke sentiments, even if detailed and vivid, but not particular scenes. It can speak to the human subconscious through the filter of the conscious (which is why you cannot “get” a music that is completely new in style to you — for example, the “learning process” one goes through when getting into death and black metal). More importantly, it cannot speak of individual ideas without the aid of words because it belongs to the instinctive understanding of humans as a species. Human nature and education mold these perceptions.

The most empty of all the interpretations was that art should be done for its own sake. A laughable oxymoron, if ever there was one. As Socrates correctly argued, art is done for the sake of the less powerful that receives it, the object of its mercy. For music, that is the human spirit, the subconscious and the conscious as a whole, your state of mind, whatever you wish to call it.

II. The options that metal has at its disposal

In his Fifth Heretical Essay, “Is Technological Civilization Decadent, and Why?”, Jan Patočka briefly goes over the topic of pre-history (which he clarifies does not mean non-history), its transition into history and humanity’s ascending from an animalistic lifestyle to one where one’s considerations extend beyond personal immediate necessities.

Pre-history for humans was characterized by having survival itself as a main preoccupation. Life for life’s sake. Setting the conditions for historical life, humans moved into settlements and gradually were able to afford independence from the every-day fight for one’s life. The price of this was work. This work became a responsibility in exchange for safety and space to indulge in pleasurable activities. Patočka refers to the second one of these as the the orgiastic, a release and exchange from the toil of responsibility that provides an escape from a life of pure survival.

This sort of life could still be considered as life for its own sake. The clever reader may observe that in the previous description a full circle is described. Each activity on the stack is concerned with an individual trying to escape the previous state in order to keep going, to ensure survival.

It is then that the transcendental, the sacred, the divine, the ulterior, makes an entrance into human awareness. This is not to be confused with religion, which is only a systematic arranging of rituals and beliefs which may or may not be a way to the divine. Independently of the system chosen or the disavowal of all systems, keeping something larger than ourselves in perspective can make us redefine the way we see our individual lives. Our lives are no longer lived in redundancy, just in order to keep living, but are charged with energy and will power to build or attain something without the intention of receiving personal reward. (Remark: It is common for people to have kids in order escape their mundane lives, but their intentions are equally mundane and selfish, mostly bringing children they cannot properly raise to an overpopulated world in order to satisfy their empty lives. The transcendent ideal goes beyond such gimmicks of self-deception .)

Thus we can descry three possible avenues for music:

- For mere function in context (responsibility)

- For pleasure itself (the orgiastic)

- As a medium to perceive and keep in sight something larger than our individual human lives (the transcendental)

The nature and goals of different music, perhaps to different degrees rather than in straight-up black-and-white distinctions, can be classified using these three elements. Music that is deemed superficial is that which lacks in transcendence. Mainstream (a term that only makes any sense from the 20th century on) music, specially, can be said to work in the primitive paradigm of responsibility on the side of the artist and pure orgiastic pleasure on the side of the listener. In most music, this activity is usually a combination of both on the side of the musician, responsibility to norms in order to get his pay and an attention to how much pleasure the music provides him. A reflection of life for life’s sake in an empty music devoid of any transcendent meaning.

Transcendental music and art in general would imply musicians being invested in the music for something larger than their own personal profit (monetary or otherwise) and an audience similarly invested and discerning of music that gives them that sense of going-beyond their individual lives. All the songs about common love, friendship and equality notwithstanding as they only serve to comfort weak individuals in their self-pity, not propel them forward to greater heights were the self is at least partially dissolved.

An example of a middle-of-the-road agreement would be Johan Sebastian Bach, who, like any man living off of music has to fill certain requirements. At the same time, he is renowned to have constantly searched for an ideal in music that would reflect the divine through proportions and relations, guided as well through a crystallization of rules in smoothness and logic that results from a fastidious attention to natural human perception of intervals (artists two hundred years later did the opposite…). In practice, he often got into trouble and wasn’t the best “worker” in the sense that what he produced was seldom exactly what was expected of someone in his post. But he survived, was honored by the clergy and royalty alike and his music outlasted him because the society in which he lived (Germany in the late 17th and early 18th centuries) valued the transcendent, the divine, above anything else. Cynics can stop laughing, of course Germans at the time also fought wars and had to take care of business, and so did Bach. Following a transcendental path does not mean you are exempt from the toil and eventualities of life.

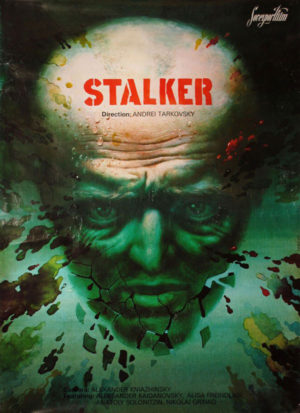

That metal’s nature is that of a transcendental art can be proven by pointing out the way in which it developed. As we have previously described before, each metal stylistic development had to do with a shedding of aesthetics in which it lurched forward away from the mainstream and into more distinct characteristics that would set it apart from rock music and in a rebellious statement of intention that stated its anti-establishment position. But in contrast to punk and other protest music, metal was not anti-authoritarian out of a social revolutionary sentiment, but from a nihilist-realist point of view. It was a reducing of humans to ants in an uncaring universe by using Satanic, pagan or occult imagery to depict concepts that stay true from antiquity to this day. This is the same reason why metal is so prone to using fantasy fiction themes. Metal is not an escape, it is reducing of this pseudo-reality to what it actually is: one of many possible constructs.

Individually, this or that artist may believe or use the imagery and language they adopt, but as a whole, metal is none but that transcendent essence that refuses to bow to the arbitrariness of present human status quo. In its place it does not propose anarchy or freedom, but calls for an awareness of reality as existing outside human expectation, want, need or hope. It is a confronting of reality instead of a twisting of truths for the shielding of and maintaining of mundane activities for the sake of staying alive peacefully and pleasurably. More importantly, this confronting of reality does not imply a fatalism, but a way to emerge triumphantly, seeing through individual situations and times, recognizing our place in nature and our dependence on it.

III. Implications in Practice

How does this translate into music? Is art more than just its intention or its random interpretation by an audience?

In his discussion, Patočka made three important distinctions in order to better attack the problem of the decadent. The separation between meaning, significance and purpose was stated functionally different. Meaning is the most difficult of these to grasp. It is not a value, nor is it the same as purpose although they could fill a same role in certain circumstances. Meaning is said to make something open to reading, to a sense, to understanding of something that is as it is. Purpose itself is the reason or intention why something is carried out or why it is brought into being. Significance is concerned with its relative role or function in relation to a particular context.

Purpose and significance are subject to times and context. Meaning is not. The meaning of something can be interpreted to have different significance in different places, or it can be used for different purposes. But what it is does not change, and so its meaning does not. The distinction between purpose and significance is of the utmost importance when it comes to understanding and judging music. The purpose of musical devices is often confused by individualists and relativists to be one of the other two. The purpose of music matters little to the music critic who is charged with judging its quality and not its good intentions. The music critic cares only about significance.

But I propose a slightly different mapping in which the human mind, not the rest of the universe, is the world of action for music. After all, music is artificial, it is made by us, for us and it is its effect over us that matters. Therefore, meaning can be redefined in the context of universally perceivable effects in patterns, textures and intervals. Universally as in across the human species. It is to be expected that there is a variance in the effect, but that does not detract from the existence and relevance of a mean.

The definition of purpose need not change, it still lies in the reason why a certain music would be made. Now, significance would shift to being the acquired role of structures and relations in different music paradigms, different genres, different traditions. That means that just as different spoken languages, music can have its own rules arising from conventions between human perception and arbitrary organization. But the more arbitrary it is and the less it conforms to natural human perception, the less capable of transcendence a music is. This does not mean that education cannot be involved. But education can reinforce and deepen what comes naturally and follows the path of human potential (Common Practice Period), or it can be capricious arbitrariness arising from the fallacy of the human mindas a blank slate (see Serialism).

Two things need to happen for a transcendental music tradition to be sustainable. The first is artists that are devoted to the transcendental aspects of music. The second is a discerning audience. Part of this discernment is a certain trust in musicians, their own vision and values as well as their abilities. This is the same sort of trust we have for leaders of any kind, be them rulers or scientists.

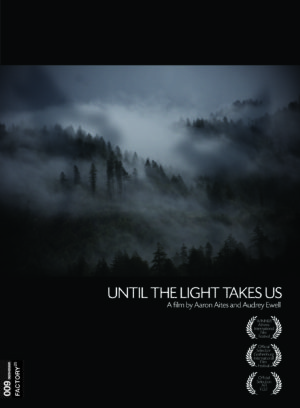

The reason why we do not have this trust in musicians in modern times is because as a result of historical processes, they have come to disgrace themselves. The sort of respect for artistry and trust in their distinction above ours survives today only in very dark corners of human action like specific classical music niches and extremely underground metal and ambient circles. In metal, these are the sort of circles that remain willingly untouched by labels in order to keep their art at away from vulgar and unworthy reception. These remain the last bastion of metal against the taint of the mainstream.

It is in understanding there is something more to human nature and human experience that is both innate to us and that we share with other human beings, that we can also come to respect the power of transcendental music: music that taps into these aspects. Music that has the power of directing human conscience in a particular direction, as well. Today, underground metal is one of the few musics that go beyond the merely functional or the pleasurable. This is music that has the power of cultivation, of expanding the mind, of looking beyond your own fear of the unknown, of inevitable death and into the future of humans as a species and not just you as an individual, but as an individual channeling the species into a more aware future.

IV. The Transcendental: Art for the Sake of Human Evolution

It is no surprise that we can trace a very clear line from the 18th century to the 21st at the beginning of which art is universally sponsored by the ruling classes and institutions of power that through gradual changes becomes increasingly independent (19th century) and later on less connected to human nature (20th century). This culminates in a complete stagnation in the 21st century, our times…

The question of true transcendental art being underground or not depends on the current values of society. In the case of our modern society, its purely materialist and ultra-democratic outlook that dictates that personal caprices matter more than reality is the antithesis of the environment where a transcendental — one that reflects enduring meaning — art can be fostered.

By definition, a materialist civilization that attributes no meaning to anything except the massing of perceived riches or power, cannot produce such an art. That is to say, such a civilization does not even believe there is such a thing as the trascendental. Furthermore, this materialist outlook is based on an absurd pushing of boundaries through a rational point of view taken to an extreme. But anything taken to any extreme loses contact with reality, which is itself an amalgam of degrees of many different qualities — compromises between opposites.

A rejection of reality in favor of an artificial extreme such as materialism is then enabled to brush aside and subvert anything that does not conform to itself. This includes human nature itself. In fact, the materialist position claims there is no such thing as human nature. This enables the power-hungry, the greedy and anyone else to try and clean their conscience through a pandering of the idea that we are only the result of the cultures into which we are born and values are only social constructs. The dogma then becomes: power is the only objective measure of success. A side effect of materialism is the idea that everything we perceive is subjective and therefore not subject to judgement or control. All that matters is if I think this or I like that. The weakling’s alternative to the dogma becomes: happiness is the only subjective measure of success.

Both of these emphasize an enlarged “living in the moment” that favors egoism that, as proven by history, results in an almost complete disregard for others’ living in this same present and those yet to be born — unless an immediate reward/punishment is offered to the materialist individual. The transcendental provides precisely the opposite: a view into the characteristics that make you human, that dictate our nature, that both unite us and make us different. As Steven Pinker summarizes in his book The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature, this flies in the face of research that has in turn been suppressed and vilified by an establishment eager to maintain the status quo in a similar gesture to a superficial Church censoring scientific discoveries centuries ago.

Also contrary to a short-sighted reading, this should not result in us embracing the understanding of one’s own nature as licence to indulge in it, but rather a precise knowledge of how to control it and channel it in order to become better. A transcendental view of time and values applied to our species may pave the way for not only a widespread search for individual enlightenment but a species-wide one. One in which humanity works together for its own good, which at this point would translate into a caring for the planet it is destroying in the vulgar self-interest dictated by materialism.

The importance of metal as this transcendental art is its power to maintain this knowledge and to promote universal values and even more importantly, their understanding. The reaction of materialism and the religion of scientism against the notions of transcendental value are emotional to their very core but also based on observations of how values defined arbitrarily in the past lead to social disasters. This, combined with their own superficial and strictly functional misunderstanding of the values prevented them from fully becoming aware of the underlying human need and impulse to reach for something beyond the material and the every-day.

This is why those who understand such transcendentalism treat the mainstream with opprobrium and an extreme disgust. As with anything else, the attitude of those who understand can be confused with those who follow and do not understand, those who adopt attitudes — even pseudo transcendental ones — with the ulterior motivation of immediate reward to themselves. And thus elitism and the upholding of all that is truly excellent is marred and disgraced by a civilization of insecure and selfish individuals who cannot see past their own self-interest, a selfishness that is then projected onto those who they judge because they cannot conceive of anyone actually believing and acting for the sake of something larger than themselves.

Nietzsche is reviled by the religious (who, in general, have never read him, let alone understand him) and by the materialists (or at least those have read him, those who haven’t or do not understand seem to think him some sort of atheist hero). The main reason why materialists despise him is because he is a realist. Realism flies in the face of extreme and delusional reality-deforming conceptions of life such as materialism. As a realist, Nietzsche recognizes the inherent human need to believe in something outside himself. For those who have been paying attention, it is obvious this does not necessarily imply some sort of superstition or dogma.

Nietzsche’s Übermensch (the “superman”, the “overman”, the superior human) as described in Thus Spake Zarathustra, is one that sees and goes beyond his own times. One that is not trapped by the paradigm of his contemporary society and that furthermore excels himself above his peers in a work. This sort of talking can be taken metaphorically, but it is not meant to be. Going beyond one’s own times has to do with recognizing history as a set of changing variables within a timeline on an unchanging or slowly-changing human nature where a set of set meanings remain constant for us but are, perhaps, difficult to see.

It is in the of going over and overcoming of common man who is little more than a tamed beast, that we humankind can continue on their learning and growing path as a species. This is the nature of the transcendental. The individual transcends in his perception of his people and time and contributes to a flow of which he is only a part. Only then can the species attain a transcendental vision in which it is not only looking at its immediate problems but at its long-term development ten or twenty generations in the future. Would that we could see such a civilization arise, it would be a beautiful sight to behold.

V. The Transcendental in Action through Metal

Arising from the context of popular rock music in the late 1960s with a different musical method and a realist mentality, metal veiled its message behind mystic frontispieces that became whole with the dark romantic aura behind its motif-driven music. The classical romantic tradition that so influences it has as one of its focal points the return to an intelligibility and “naturalness” that was most readily searched for in taking hints from folk music melodies and rhythms from different rural landscapes around the world (primarily from Europe, unsurprisingly). This did not mean a ridiculous simplification of music to banal catchy lines, but a simplicity of which Plato’s Socrates spoke.

Then beauty of style and harmony and grace and good rhythm depend on simplicity,–I mean the true simplicity of a rightly and nobly ordered mind and character, not that other simplicity which is only an euphemism for folly.

— The Republic, Book III

Musically, what is transcendental must necessarily be atemporal, it must have the capacity to communicate with human beings from any historical (or pre-historical, for that matter) period, age or walk of life. This does not mean that the connection has to be instant or that the listener does not need to go through a “learning process”. In fact, in the particular case of metal as a veiled teaching, it is only through maturity in understanding it in a holistic manner that one comes to understand the truths that several great musicians with piercing views about what it is to be human reflected through it.

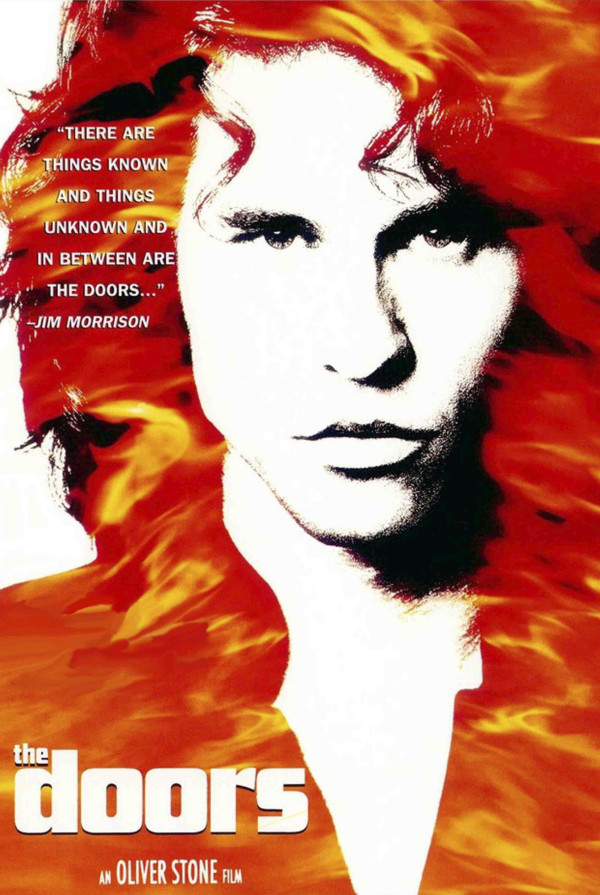

Despite the influence, there is a very sharp contrast between classical romantic music and metal. The difference is a consequence of the historical context, particular social class and sentiment out of which they each arose. Romantic art came from both the need of the individual to find a place and expression of his own, not in the modern selfishness of the individualist, but a place in nature and in reverence to it. A connection to what it is to be human. As classical music, its prestige and the station of those making it allowed it to pursue such things in broad daylight. To this, we should add the nontrivial matter of the nonexistence of recorded music or other conveniences that flood and distract listeners. The expression of the romantic artist could be full and undisclosed.

Metal, on the other hand, comes in a time where popular culture reigns in saturation of kitsch: superficiality and banality for the immediate pleasure of the distracted and manipulated masses. Less important but worth mentioning is that it originated in strong and independent-thinking middle-class individuals who saw through the deception of their times. Several choices in its underground character come from this. As an art form that subverts the ruling falsehood, it is not allowed to be displayed directly. The fact that being an intellectual resistance also means that not all can understand it and that its concerns go beyond the present manifestation of human society and its dogmas require that it is not fully out in the open. It must assume a mask that reflects an outer and simple intent that keeps most at bay to guard what it contains. Its identity must be more distinct and defined than its predecessor and so, willingly, metal takes on a much more limited range of expression than classical romantic music from the 19th century.

Of the harmonies I know nothing, but I want to have one warlike, to sound the note or accent which a brave man utters in the hour of danger and stern resolve, or when his cause is failing, and he is going to wounds or death or is overtaken by some other evil, and at every such crisis meets the blows of fortune with firm step and a determination to endure; and another to be used by him in times of peace and freedom of action, when there is no pressure of necessity, and he is seeking to persuade God by prayer, or man by instruction and admonition, or on the other hand, when he is expressing his willingness to yield to persuasion or entreaty or admonition, and which represents him when by prudent conduct he has attained his end, not carried away by his success, but acting moderately and wisely under the circumstances, and acquiescing in the event. These two harmonies I ask you to leave; the strain of necessity and the strain of freedom, the strain of the unfortunate and the strain of the fortunate, the strain of courage, and the strain of temperance; these, I say, leave.

– The Republic, Book III

It is also important to understand the outer and the inner manifestations of the spirit of music. There is a learning process to each kind of music, because outside is manifested the tropes of a region, culture, group, perhaps a particular “language” or set of conventions. By basing itself on patterns and harmonies the human ear feels naturally drawn to, the music is aligning itself to what is permanent to human perception, at least in this point of our evolution. But all these are developed, “discussed” in a music that speaks a very particular mind. Just as Plato might have spoken in ancient Greek about similar things we would speak of today in modern English, so it is that transcendental music from music separated by centuries might be speaking the same message under different grammatical guises — tropes and conventions of times and style. The act of the Dionysian manifesting itself through the Apollonian as the young Nietzsche described to us in The Birth of Tragedy.

Someone might ask if it isn’t better to disavow all conventions and try to speak in “plainspoken transcendental”. The innocence of such a suggestion comes from the incorrect belief that what is felt, what is understood and experienced wholly as a human being can be put purely, clearly and unambiguously into words. Necessity dictates that emotion and experience be transmitted to the innermost core of the individual– a penetrating of various layers of prejudice and consciousness in order to move the primal and ripple back through to the higher, if possible. Neither mere words in their plain meaning nor musical structures on their own, in the beauty of orderly symmetry and mathematical correctness can achieve this. These only speak to the higher intellect, which may or may not translate this to the deeper self.

Reaching the innermost sanctum of metal, though, requires much more than being touched by it. For that to happen, metal cannot just be a passing entertainment or the object of devoted fanhood alone. It needs to be taken seriously and read correctly in its contradictions and flagrant imagery that bespeak a connection to the transcendental beyond mere unambiguous pattern codification. It is not a science in the modern sense and is more akin to occultism and its voluntary hiding-away. Following from that, we may infer that it is far more esoteric than exoteric, this latter being ridiculous or incomprehensible when taken at face value. Only treading the serpentine and treacherous paths through cycles of internalization and externalization does the metal fan become the metal initiate.

39 CommentsTags: friedrich nietzsche, Heretical Essays in the Philosophy of History, Jan Patočka, metal, Philosophy, plato, Socrates, Steven Pinker, The Birth of Tragedy, The Blank Slate, The Republic, Thrasymachus, Thus Spake Zarathustra