It’s no big news when someone who grew up two decades ago prefers to buy CDs. Back then, the shiny little discs represented a break from the cumbersome technology of the past and instead were a gateway to modernity.

It’s no big news when someone who grew up two decades ago prefers to buy CDs. Back then, the shiny little discs represented a break from the cumbersome technology of the past and instead were a gateway to modernity.

Not so, now. People growing up in the last decade have emerged in a world where “buying music” increasingly means downloading a song from an iTunes or Amazon account. The idea of buying physical CDs is as odd to them as buying a player-piano scroll.

However, there are always those who don’t go with the flow. We found a user named Evisceratorium at large on the internet who is willing to tell us about the decision as a new listener to go back to buying physical music instead of digital.

I understand that you’ve grown up with the digital download generation, but have switched back to buying CDs. What were your reasons for doing this?

I decided that the overall experience of buying physical music was more interesting and fun than simply pulling up a downloading website and clicking a button. It simply started as an alternate way to own music, I guess — I didn’t consider one way of doing things to be superior to any other. If I was at the record store in the mall and I saw an album that I was interested in checking out, I’d buy the CD there instead of getting it off iTunes, if only for immediate gratification and convenience.

Do you think there’s a value in having a tangible product? Do you have your collection on display, or use it as conversation pieces?

I think there’s a lot of value in owning the tangible product, especially for musical formats. It’s not just a sign of devotion to me, it’s a token piece that I get to keep and look at whenever I’d like. I’ll admit that, contrary to most somewhat similar opinions I’ve heard, I don’t buy music to support artists I enjoy. If I enjoy them, that’s fine; but frankly I usually expect to receive some item in return for my money and support, rather than something intangible. I do have my collection on display — Discogs.org says I have 280 items on some format or another as of right now – and yes, I do enjoy talking about it to other people. I like going through other people’s collections and comparing their albums to my own, too, so I appreciate it when other people talk about their finds as well!

But to be entirely fair, I don’t have this same sort of attachment to physical formats of other media like movies or books. I don’t feel like people should be obligated to acquire every single thing they want in physical form, because even I don’t really do that for things that aren’t musical; but if you’re truly passionate about something, you should seriously consider having pieces of your passion there for you to touch and observe, because it really is a great feeling.

Do you know of any others who have made the same decision?

The same general principle, yes, but I don’t personally know anyone who mirrors my personal philosophy verbatim. Most illegally download most or all of their music, or they physically buy most of it but download when the item in question is rare or out-of-print. I’ve never done that: if an album I want is out-of-print then I wait for it to become available for sale, if it’s brutally expensive I save up and then get it, or if it’s not available I don’t acquire it period. It doesn’t mean I want it any less than anybody else, but I don’t see why I can’t wait to own it like everyone else did. I think a lot of the people who download work mostly off the concept of instant gratification, which I think hampers the excitement of music quite a bit.

Besides, anyone reading this is already utilising the giant resource that is the Internet, and with a bit of digging on the buyer’s end, I would argue that (excluding most demos from decades-old bands, I’ll admit that these tend to be unattainable) most “rare” or “out-of-print” albums are a lot easier to find than most people would like to think. Expensive? Well, of course, you’re trying to get a product that came out 15-20 years ago and has been spread throughout the world since, or a product that was limited to 50 or fewer copies and is only now being relinquished by one of the fans who originally acquired one. But if you want it, it’s definitely there. Even Bathory’s infamous “yellow goat” LPs are a couple of clicks away from being yours, according to Discogs. For nearly $1,000, yeah, but if you really want it that bad, it’s there. The whole “downloading old stuff is okay because it’s not there” comes off to me as a side effect of the Internet age: a combination of impatience and a retrospective sense of entitlement. In other words, the Internet is attempting to transcend the limits that were originally set by the record labels in question and I don’t appreciate that. But I’m starting to digress from the point. Basically, no, I don’t know anyone who embraces physical formats as adamantly as I have, though most of my friends buy physical copies of albums to some extent.

Other than the reasons for which you initially started buying physical copies of music, have you discovered any other advantages?

Quite a few, actually. Physical albums are much more likely than digital files to contain vital information about the album which one might be interested in. I’ve seen tons of posts on forums where people asked about the lyrics to certain songs and the answer was right there, plain as day, in the booklets of the albums in question. More subjectively, I think they’re a lot nicer to look at, the variety between stuff like digipaks, cassettes, box sets, and LPs is nice and gives each item a more unique identity, and for me they make me develop a closer relationship to the album than if it were only a bunch of files. (You can see this in terms of interpersonal relationships, too – proximity breeds intimacy amongst people, and I’d argue that the same can be said of people and objects.) They’re something to look at when I’m bored, admire as an aspect of myself when I feel upset, and as I mentioned earlier, they’re fun to talk about.

Another important thing is that I think buying physical items, or paying for music in general, forces people to be a bit more patient with their music, which is always good. I see so many people talking about hyper-downloading all thirteen of a band’s albums, at which point I assume those albums probably either fester on those people’s hard drives or get listened to once and subsequently forgotten. I’ll admit to having terrible self-restraint, so physical albums help me to limit myself and pay a bit more attention to everything. Put a wager of your own money into the game, and you’ll be much more likely to take things slower, appreciate nuances that you might miss on a cursory listen and be able to say more about what you listen to, instead of only being able to say “oh well duh I heard that album once, I think it’s good”. I haven’t heard that much music by quantity (there are still plenty of big-name bands where I either haven’t heard them, or I’ve only heard an album or two of theirs), but I feel like I could say a lot more about what I have heard than most other people could. Life is short, but not short enough to where you should feel the need to rush everything. Art should be given ample time and appreciation for it to sink in properly, lest we run the risk of bypassing things that we’d grow to love with a bit of patience.

This doesn’t really fit into any of the questions you’ve posed, but I’d like to briefly add that I don’t see anything wrong with people “taste-testing” music. I’ve checked out numerous bands and albums via YouTube and I don’t see anything wrong with doing so. And occasionally when I review albums I don’t own, I’ll download them, listen to them for reviewing purposes and then delete them. Free streaming and downloading are unquestionably useful tools. (Though they’re not always my preference…seriously, once you have around $20 or so, go to some underground black metal distro and buy five $4 cassettes by bands you’ve never heard, it’s a lot more fun than it sounds!) It’s when people start abusing these tools to acquire anything and everything at will that I’d say they’re starting to be abused beyond their original purposes. And yes, I’m aware that metalheads are not the most opulent subculture, but I refuse to believe that most people are so hard-pressed for money after the bare necessities of groceries, clothing, education and utilities that they are rendered completely financially unable to buy a $12 CD or a $4 cassette. This may be the naivete of youth speaking, but I get the feeling that most people who don’t have the money to waste on “inessential items” such as CDs are instead just using it on equally inessential things like food that isn’t rice, bread, or ramen noodles. When you boil down to it, music is just the same as any other luxury: you’re not entitled to it whatsoever.

Can you tell us a little about yourself, your background in metal, what sort of metal you like, and how you balance your metalness with a normal lifestyle?

I just turned 16 a month or so ago, so I guess most people would say I’m pretty young to be talking about something like this. I live in an area of the United States (read: Bible Belt) where metal music is essentially nonexistent, so that in combination with my status as a minor means I can’t really go to metal shows. I’d like to think I give back to the metal scene at least a bit, though: besides my insistence on buying albums, I post on forums a lot, and I have an account on the Metal Archives (as MutantClannfear) where I’ve posted about 130 reviews, mostly of brutal death metal or deathcore albums.

I got into metal via “the ’00s nu-metal kid’s way”. I hear lots of people talking about how they started with Iron Maiden and Metallica and trickled up through power metal and thrash up to extreme metal, but I took a much more direct route. I was aware of Metallica from earlier in my life, but my real impetus for getting into metal was Slipknot. I think I first heard them in 2008 via Guitar Hero III, and that game later led me to Rock Band. The downloadable content of Rock Band led me to Cannibal Corpse, Job for a Cowboy, Lamb of God, and Whitechapel in late 2009, and that was basically where my journey began.

I’d consider myself pretty well-rounded when it comes to metal, though my favourite genres are probably brutal death metal and the more airy, atmospheric sides of black metal. But my list of favourite bands would include stuff like Dark Angel and Black Sabbath, as well, and my favourite band of all time would be Lykathea Aflame. I never really shed my roots as I still listen to nu-metal and deathcore, and even find both styles growing on me a bit the more time passes. I don’t feel like I need to “balance” my metalness out with the rest of my life, per se. I’d consider myself more of a general music fan than a metalhead, and though metal is my favourite genre of the bunch, I feel like I enjoy a bit of everything (though my tastes have primarily been modern pop music lately). Outside of the shirts I wear, I don’t try to be ostentatious about my tastes in music unless people ask. And yes, I give non-metal genres the same attitude towards purchasing physical music: in fact, the last two CDs I bought were by Ellie Goulding and Ke$ha, oops.

Sorry if this rambles a bit, but I’m a bit tired and I feel like I had a lot to say. All in all, I think the physical side of music is a thing that goes greatly overlooked now that people can effectively bypass it, and I’m damn proud to see the metal scene in particular fighting to keep it alive for as long as it has. Thank you for giving me the opportunity to participate in this interview!

And there you have it. Start buying CDs, because it’s a great way to experience music. Or vinyl, if your tastes run to that. Thanks Evisceratorium for a great interview!

14 CommentsTags: compact disc, interview

Obliteration – Nekropsalms

Obliteration – Nekropsalms Sarcofagus – Cycle of Life

Sarcofagus – Cycle of Life Chtheilist – Amechthntaasmrriachth

Chtheilist – Amechthntaasmrriachth Ofermod – Tiamtu

Ofermod – Tiamtu Entrails – Tails from the Morgue

Entrails – Tails from the Morgue Sargeist – Let the Devil In

Sargeist – Let the Devil In

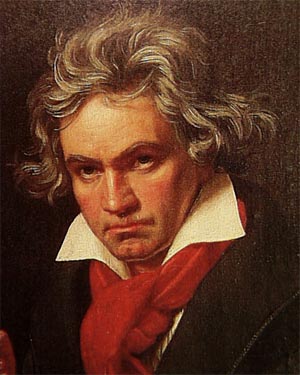

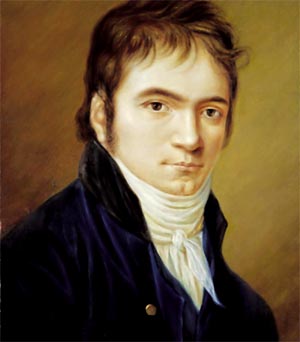

For kicks I decided to listen to nothing but classical music for a month. Having bounced around looking for the next genre to capture the power of old school metal, I realized that none were coming close, so skipped the drama and went right for the heavyweight — classical. In specific, I’d found the following frustrations:

For kicks I decided to listen to nothing but classical music for a month. Having bounced around looking for the next genre to capture the power of old school metal, I realized that none were coming close, so skipped the drama and went right for the heavyweight — classical. In specific, I’d found the following frustrations: Because of this, I chucked aside the notion of listening to popular music — at all. Even if it’s underground or indie, if it’s in the popular music format, that’s how it will be perceived and treated, which in turn affects how I’ll have to interact with it and get ahold of it. Specifically, I noted how the greatest artists were straining to escape the kiddie music ghetto, like Tangerine Dream, Kraftwerk, Fripp and Eno. Why keep pushing the dead agenda?

Because of this, I chucked aside the notion of listening to popular music — at all. Even if it’s underground or indie, if it’s in the popular music format, that’s how it will be perceived and treated, which in turn affects how I’ll have to interact with it and get ahold of it. Specifically, I noted how the greatest artists were straining to escape the kiddie music ghetto, like Tangerine Dream, Kraftwerk, Fripp and Eno. Why keep pushing the dead agenda? Finally, there’s a time difference. Rock music is three-minute songs, with a few exceptions. Classical music has some three-minute songs, but more commonly, longer pieces are composed of several movements. Themes are shared across these movements, like a conversation with question, answer, debate, modification and restatement. You can’t hum a melody knowing that in thirty seconds, after the chorus, it’ll be back.

Finally, there’s a time difference. Rock music is three-minute songs, with a few exceptions. Classical music has some three-minute songs, but more commonly, longer pieces are composed of several movements. Themes are shared across these movements, like a conversation with question, answer, debate, modification and restatement. You can’t hum a melody knowing that in thirty seconds, after the chorus, it’ll be back.