We covered Condemner’s Omens of Perdition recently and found quite a bit to like in its death metal stylings. When the band reached out to us for an interview, staff writer Corey M rose to the occasion and spoke with the band members.

CM: First, please introduce yourselves and describe your roles in making Condemner’s music.

PB: I am PB. I play guitar and handle drum programming, song writing, and, thus far, most lyric writing.

JH : I am JH and I provide all vocals and bass.

CM: Can you give us a brief history of Condemner? What inspired you to write and play metal?

PB: As an entity, Condemner was formed in October of 2015, but the seeds of it date back to Summer of 2009. At that point, I had been playing guitar for a few years, but everything I wrote was black metal in a harmony-heavy style reminiscent of French bands such as Mutiilation or Haemoth. At the time, I felt that death metal was too limited; I had, incorrectly, perceived it as a sub-genre that was almost entirely focused on immediate facts of what we see in front of us in the world, entirely sacrificing the “spiritual” in the process; focused on the phenomenon, rather than the noumenon, for those who dislike such “religious” descriptions. What changed all of this was seeing Imprecation live for the first time in Summer of 2009. That band’s performances conjure the dark aether in the way that I had only associated with black metal. This revelation, combined with the fact that I felt like my black metal songwriting was a bit overwrought and emotionally overindulgent and needed more discipline, made the path clear to me, and I started writing death metal in the style that you hear on Omens of Perdition. “Reverence Towards the Pernicious Tyrant”, in particular, dates back to these earliest days. Originally, I didn’t have any plans to turn it into an actual band, and was just writing the songs for my own pleasure, with the occasional quick-and-dirty guitar-only recording so I could easily remember my own material, but a friend and mentor in the Texas metal scene who I have the highest respect for told me to turn it into something “real”, and shot down every excuse I made for not doing so, at which point I started learning drum programming, multi-tracking, and the rest of the things that would be required to make a proper recording.

As for what inspired me to write and play metal as opposed to something else entirely — I’m was a hessian before I was a musician, so I was obviously going to write what I love.

JH: I will only speak to my own history in Condemner: I was approached to record vocals on Omens of Perdition in late winter 2015 and took over the bass duties when the individual that was originally going to record bass dropped out of the project. I learned and recorded all of the bass parts on Omens of Perdition in less than a day and completed the vocals a short while later. The demo was digitally released in December and the reception has been very positive in the underground.

The initial inspirations for myself (assuming we’re starting from the beginning) were the usual suspects of ‘80’s Metallica, Slayer, and Sepultura as a teenager which led to bands like Voor and Slaughter (Can.) which led further down the path of death metal, black metal, etc. Inspirations as far as vocal performances for Condemner are Ross Dolan of Immolation, Nick Holmes of (early) Paradise Lost and Chris Gamble of Goreaphobia for their articulation of lower growls. Craig Pillard on the first two Incantation albums was definitely an influence for the demo as well. MkM of Antaeus is always an influence — although I am using my lower range in Condemner instead of my typical higher range, MkM’s intensity is something that resonates with me regardless of which range I am using. Finally, Rok of Sadistik Exekution is an example of the complete primal fury that every metal vocalist should attempt to channel.

CM: Condemner’s lyrics read like actual worship of death as both a real eventual experience and an abstract concept personified by an evil force. Is this on purpose? And if so, how specifically do the lyrics fit with the rest of the music?

PB: This is on purpose, but it’s a means, not an end. Speaking for the three songs I wrote the lyrics to, the key concepts are strictness and severity. Often in death metal, evil and Satan are seen as stand-ins for liberation and freedom, but there’s another side to this coin — not just opposer, but accuser as well. Black Sabbath wrote “Begging mercies for their sins/Satan laughing spreads his wings”, Slayer wrote “Bastard sons begat your cunting daughters/Promiscuous mothers with your incestuous fathers/Engreat souls condemned for eternity/Sustained by immoral observance a domineering deity”, Immolation wrote “Glorious flames… Rise above/Show us pain… And cleanse our world”, and Condemner follows along the same lines, seeing death, evil, and Satan as the whip that justly lashes across the back and the flames that rightly burn the flesh of weak, failing humanity. This is the source of the band’s name, as well as the lyrics — “Condemner” is an antonym for “pardoner”. No forgiveness.

As for how the lyrics fit with the rest of the music, the music is always written first (writing lyrics-first is part of what caused my older black metal works to be overindulgent), and then words are written to match the composition — first, more generally, as a song title, and then, more specifically, as actual lyrics. Some might notice the parallel between the lyrical topics and my own intent for the music here to be more disciplined than my previous works, but this wasn’t intentional; I didn’t notice it myself until long after I had already decided on Condemner’s concept.

JH: I can’t speak so much on the writing side of things, but I would say that I see death as a force to be honored and revered for its might. I prefer to not speak too much on the matter but the lyrics I contributed for the demo’s final track “Blood On The Oak (Death’s Wisdom Great)” are about an experience I had in which I was confronted with that might. It was a triumph of death, to say the least. I relate my own experiences to PB’s lyrics as well, although again I will not speak much on the subject.

I would completely say that the lyrics fit the morbidity of the music — any other lyrical topics would be monstrously out-of-place for an atmosphere like this. Interestingly enough, the lyrics for “Blood on the Oak” were initially written in late 2014 and were used in two different bands that each split up before the song could be recorded, but I would say that it has found a perfect home in Condemner.

CM: The individual riffs on Omens of Perdition are relatively simple when compared to what a lot of contemporary so-called “technical” metal bands are doing. Was that simplistic approach something that you chose on purpose or did that style of having all your instruments playing melody in unison just come about naturally?

PB: The riffs on Omens of Perdition aren’t technical because I don’t like the music that most “technical” metal bands make. With a few exceptions (Demilich!!!), it’s all attention-grabbing pyrotechnics with little portent behind it. It wasn’t a conscious decision — there’s no way that someone who loves Profanatica and hates Necrophagist is going to make something like Necrophagist. As to the instruments playing in unison, that was simply a result of how the songs were written — as mentioned earlier, all of the music was originally written for a single guitar, so the other instruments were always destined to follow the guitar.

JH: For the bass, everything is kept simple and following the guitar parts for maximum force and impact on the listener. I see Condemner as following the Tom G. Warrior school of “less is more”, and I’d say that the end result was successful.

CM: Can you explain (in as great or little detail as you want) the process of writing a song? Does it begin by jamming until new riffs emerge or is there a more structured method?

PB: Generally, it starts with me coming up with a melody in my head, and turning it over in my head for a few days, silently humming variations of it to myself. Once I’ve done that, I can generally pick up my guitar and write riffs that complement the one that I had in my head with little trouble, and then I can work on expanding that narrative, writing contrasting riffs and looping the structure back on itself as is fit. The real meat of the process, though, is simply playing the song until there’s something about it that I dislike, fixing that problem, and then repeating that process over and over. There’s one song on Omens of Perdition that’s an exception to this rule — “Executioner’s Canticle” was built around a structuring technique I had noticed Morbid Angel using on “Maze of Torment”.

JH: Currently PB writes all Condemner material and most of the lyrics (I wrote “Blood on the Oak (Death’s Wisdom Great)”); an arrangement that is working well. PB and I are located several hours apart and lack a human drummer, so “jamming” in the traditional sense isn’t really an option.

CM: Being from Texas, are you part of a uniquely regional style or does your expression of death metal run counter to any regional paradigm?

PB: I don’t think there really is a “Texas death metal sound” in the way that there’s a “Stockholm death metal sound” or a “New York death metal sound”. That said, I think it’s obvious that Imprecation and Blaspherian had an influence on Condemner’s style.

JH: While Texas has some of the strongest contenders to the death metal throne in its ranks, I would not say that Condemner sounds like many acts within our region. I believe that the closest would be in the form of some of the Houston death cults such as Imprecation and Blaspherian, but we are far from clones.

CM: What are the plans for Condemner’s future? Do you intend to gather a full line-up for live shows?

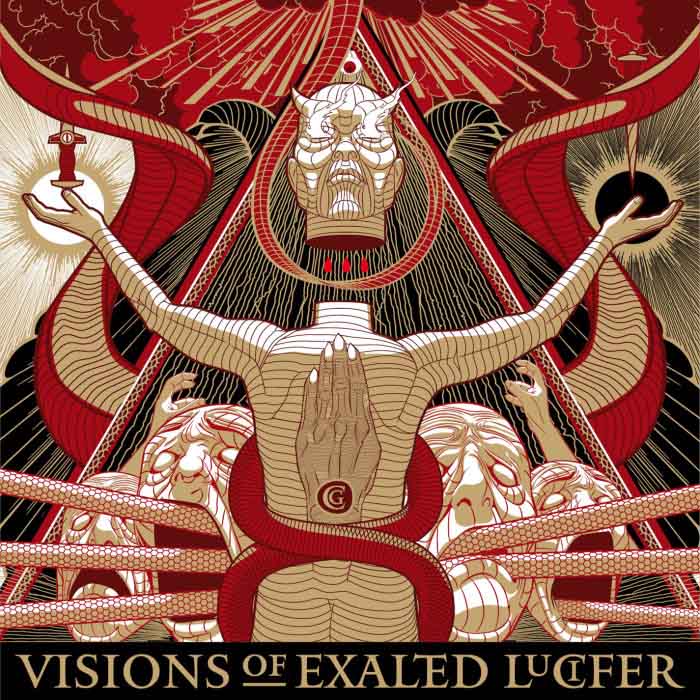

PB: No live shows are planned. I’m not opposed to the idea, but JH and I live about four hours apart, so logistics for rehearsals would be difficult. As for what’s planned for the future, most immediately, physical versions of Omens of Perdition will be coming soon — ZKD, whose work you have seen on the cover of all three issues of “Under the Sign of the Lone Star”, has agreed to do the cover art. A second demo, “Burning the Decadent”, with four more songs written in the period from 2009-2015, is planned; I currently plan on beginning the recording process in the Spring, which means you’ll probably hear it some time in the Summer. What happens beyond that is unknown, and dependent on the resources available and how long it ends up taking me to write new material.

JH: The reception to Omens of Perdition has been killer for sure, and there will certainly be new material. There are plans for a physical format of Omens as well, as the cover art is still in progress.

It would be great to perform these songs on a stage some day, although PB and I are currently separated by a distance of several hours which makes the idea of rehearsal logistically complex. I also maintain a heavy schedule with other bands not named here (as I do not want Condemner to be any “featuring members of X” act – it stands on its own) which adds complications to the idea of getting together to play live. Still, I certainly wouldn’t rule it out in the future, especially since live session members wouldn’t be hard to find within my network.

CM: Any last words?

PB: Thanks to Deathmetal.org, both for the support of Condemner, and for keeping the flame of the DLA alive! As mentioned, physical copies of Omens of Perdition will be available soon– keep an eye out!

JH: Thanks to all who have supported this group in its short existence, including Left Hand Path Designs for the excellent logo. For the unaware, Omens of Perdition may be downloaded for free on the Condemner Bandcamp (a pay option is also provided for the inclined). Nothing more needs to be said — the music speaks for itself.

6 CommentsTags: 2015, condemner, death metal, interview, omens of perdition