Academia’s recent acceptance of metal comes in several prongs. One prong is the study and publication of theories about metal; another at a more fundamental level is the teaching of metal and analysis of metal to a new generation.

Academia’s recent acceptance of metal comes in several prongs. One prong is the study and publication of theories about metal; another at a more fundamental level is the teaching of metal and analysis of metal to a new generation.

Professor Josef Hanson of the University of Rochester teaches “High Voltage—Heavy Metal Music and its History,” a class which studies metal as music from a theory point of view, in addition to studies of musicology and lyrics as literature. While most music studies have focused on classical or popular music, increasing recognition of the similarity between classical and metal has driven wider acceptance.

Hanson’s class focuses on the music itself, its history and its significance. He was generous enough to grant us some of his time, and to allow us to interrogate him about his teaching, modes of study and most importantly, how he views heavy metal and why it’s important.

As I understand it, you teach at the Institute for Popular Music at the University of Rochester, and you teach “High Voltage—Heavy Metal Music and its History.” Is this more of a history class, anthropology class, sociology class or art class?

Thanks for taking the time to reach out to me! I offer High Voltage through the Department of Music at the University of Rochester, where I also teach music theory, basic conducting, and direct a brass ensemble. The Institute for Popular Music is a recently formed entity at UR that packages and promotes all of our courses in popular music and also sponsors a lecture series, performances, and fellowships for those pursuing research in popular music. I like to think of High Voltage as, first and foremost, a music class, but I also incorporate elements of sociology and modern history, since it would be foolish to omit the historical and socio-cultural factors that helped forge metal. So, I suppose you could say that the course attempts to be all of those things…but the music always comes first.

How long have you been teaching this class?

I am currently completing the second iteration of High Voltage. We try to offer it every other year. In actuality, the idea started with a summer version of the course I created in 2008 called “Bang Your Head!,” which I still offer every July through the Rochester Scholars pre-college program for high school students. I think we had five or six students sign up that first summer, but it gradually gained popularity, and now I have nearly 50 undergraduates enrolled in “High Voltage.”

Generally, what do you cover?

Historically speaking, we start in the 1960s with the collapse of the psychedelic movement and progress through the decades until we reach the present day. I spend every other week on one of the major “eras”: Sabbath and early metal, NWOBHM, thrash, black metal, death, etc. In between these stops on the chronological timeline, I spend time covering broader issues like the influence of classical virtuosity and the blues, censorship, iconography, and gender. So, generally speaking, I alternate between a week of chronological history and a week focused on philosophical issues, back and forth, for the 15-week duration of the course.

What’s the typical student like who takes this class? How has student response been, so far?

The student response has been very positive thus far. I attribute this partly to the subject matter itself, and partly to the design of the course, which is highly dependent on the students identifying their interests and then pursuing them through a variety of volitional learning activities. I don’t give a lot of exams that require rote memorization or trivia-style guessing…kids today can look things up on their smartphones in the time it takes most of us to recall an album release date or obscure song title! The makeup of the class can be quite interesting. I’d say 50% of the class is comprised of die-hard fans, complete with Iron Maiden t-shirts and studded belts. But the other 50% are new to the genre, and are taking the course because they know me from another class or because they want to try something that is completely new and different for them. I really enjoy witnessing the interactions that this combination creates.

You speak of heavy metal having “an impressive history of censorship, rebellion, and redemption.” Can you give examples of each of these events?

We spend a lot of time on the PMRC witch hunt of 1985, and the rebellious response of musicians like Dee Snider and Frank Zappa. But rebellion, in a broad sense, is one of the signature features of this music, so I also ask the students to critically analyze how metal artists’ refusal to obey a host of authorities permeates their tonal and rhythmic choices, their song lyrics, and the visual and behavioral aspects of what they do. And redemption…well, there are certainly plenty of instances of something resembling redemption in metal lore, starting with Tony Iommi overcoming the metal shop injury to his fingers, thus spawning the downtuned sonic landscape that still exists today. I think redemption is one of the signature messages of the course. Heavy metal music has been reinvented, and therefore, redeemed, over and over again. You just can’t kill it. There is nothing else like it in the history of popular music.

Your syllabus says you teach “both the musical structure and the fascinating social/cultural history of hard rock.” What sort of musical structures do you have in mind? Do these correspond in any way to the social/cultural events of the time?

That line in the syllabus is meant to convey the multifaceted nature of the course: equal emphasis on the music itself AND the context in which it was/is created. In addition to reading and discussing the history of the music, the students spend time learning about the scales, modes, harmonies, rhythms, and song forms common to metal. For example, the tritone, or flatted fifth scale degree, plays a prominent role in the sound of most metal artists, from Black Sabbath to Metallica to King Diamond and beyond. So, I make sure that the students can recognize that interval both aurally and visually. And yes, the musical structure is sometimes influenced by the context of its creation, but the progressive nature of metal from a formal/structural standpoint is probably more the result of musicians simply trying to push the genre to new extremes, as the music is passed down from one generation to the next. Whether or not the pursuit of purely musical innovation corresponds directly to social/cultural events is subject to debate, but my feeling is that a connection does indeed exist on some level.

You state that students should be able to “define the separation between ‘rock,’ ‘hard rock,’ and ‘heavy metal,’ and aurally differentiate between the various subgenres within these classifications.” How do you see these different genres as being musically and culturally different? Is there a purpose to their difference? What is the role of subgenre, and why in your view is it important to distinguish between them?

Labels are a curious thing. “Rock” has become an all-encompassing term to many, and therefore, has lost its value as a label for music. The line between “hard rock” and “heavy metal” is very subjective, so what I do is simply provide the students with numerous (often conflicting) sources that attempt to draw that line. Some people claim that Led Zeppelin is the “first heavy metal band,” while others (myself included) feel that Black Sabbath is the obvious choice. My role as instructor and “tour guide” for my students is not to force feed these judgment calls; I want to help the students understand that many smart people have produced intelligent yet conflicting arguments regarding what constitutes “hard rock” and what constitutes “heavy metal.” Then, I ask my students to compose an essay outlining their own opinions and hand it in, and I am always blown away by the depth of thought they display when considering these issues. Subgenres…well, that’s another story. The seemingly endless array of subgenres in metal is incredibly unique — I’ve never seen anything like it in music. While I do feel that it is important for those who engage with this music to know what I refer to as the “core competencies” (hardcore, metalcore, grindcore, deathcore, etc.), I’m ultimately not that concerned about labels. There are many shades of grey in between one subgenre and another, in my opinion. What’s important from my perspective is whether or not the students can tease apart the various elements of each subgenre, so that they can intelligently communicate what they are hearing even if they don’t know how to label it.

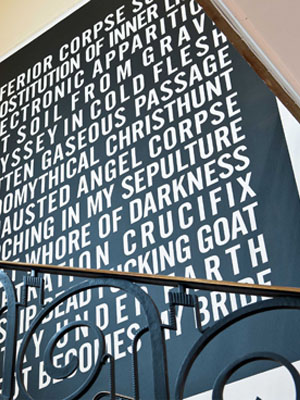

The syllabus speaks of metal lyrics as existing between the opposite poles of chaos and ecstasy. What are these poles? Do they explain the appeal of heavy metal despite its enduring negativity?

In her landmark book Heavy Metal: A Cultural Sociology, Deena Weinstein introduced this chaos/ecstasy duality, and I have found it to be a very effective way of establishing a continuum for students to use as they come to terms with the lyrics they are hearing. That being said, it is also easy to make too big a deal about the meaning of metal lyrics, which are (often simultaneously) metaphorical, intentionally inflammatory, absurdist, and unintelligible. In my class, we have identified themes of apocalypse, warfare, death and dying, and political unrest as inhabitants of the chaos pole. On the other end of the continuum, you have mostly glam and “lite” metal lyrics about alcohol consumption, sex, and generally having a good time. And more recently, extreme metal artists have written lyrics that paradoxically combine the two. So I don’t know if I would agree that there is an “enduring negativity” that defines metal lyrics…this is going to sound corny, but perhaps Danny Lilker helped coin the best phrase to describe the appeal of metal — a “Brutal Truth.” Now that’s a succinct and enduring description of the metal worldview!

You mention “myriad political/social/economic/cultural factors that forged heavy metal.” What are these, and how do you answer those who think music has no connection to phenomena outside of the music itself?

I can’t imagine a single effective argument positing that music has no connection to outside influences. Just look at the cultural melting pot that was New Orleans in the early 20 th century, or the effects of the Russian Revolution on composers like Shostakovich and Prokofiev. Metal, too, has been shaped by outside forces. There are many examples—the end of the counterculture movement and Altamont, the PMRC, Reaganomics, MTV, various wars and politicians. But the best example is the terrible economic conditions in Birmingham, England at the end of the 1960s, which undoubtedly played a role in the development of Black Sabbath, Judas Priest, and other early metal acts. In the Journal of Social History, there is a fantastic article on this very topic by Leigh Harrison entitled “Factory Music: How the Industrial Geography and Working-Class Environment of Post-War Birmingham Fostered the Birth of Heavy Metal.”

You use both Ian Christe’s Sound of the Beast: The Headbanging History of Heavy Metal and Albert Mudrian’s Choosing Death: The improbable history of death metal and grindcore (in addition to about a dozen other books!). What do you like about each of these books? Why do you use both (what does each lack)?

Ian’s book is the main text for the class, and I use it because it is engaging and well-written, hits most of the highlights required for a thorough understanding of the music, and frankly, because it is also inexpensive (the average cost of a semester’s load of books these days is over $500!). I then supplement with book chapters, scholarly articles, films, web sites, or anything else I can find. The point is to give the students a holistic view of the genre, not just one person’s perspective. Actually, part of the fun is finding the points of disagreement among several authors and debating those issues in class.

Apparently, you assign your students listening for each class period. How many songs do you assign them, and how do you select these songs? Can you show us an example playlist?

Roughly every other week, I assign a playlist of 15-20 songs (sometimes less than that). The makeup of the playlist is directly related to the era(s) we are studying and the philosophical issues we are debating. So, we might have a few thrash songs, a few early black metal songs, a few hair metal songs, and, if we are discussing gender, a few examples of misogyny in metal or a few tunes by all-female bands or bands with female lead singers. I also give my infamous “riff quiz” at the beginning of the semester, a drop-the-needle test of students’ knowledge of 30 classic metal guitar riffs.

I interviewed Martin Jacobsen, who teaches a class at West Texas A&M University about metal lyrics and their significance as literature. Do you analyze metal lyrics, or do you view them as secondary to the music itself (guitars, bass, drums, vocal rhythms/textures)? If you do analyze lyrics, how do you do it?

Metal lyrics are incredibly interesting and certainly qualify as a form of literature, in my opinion. We do a bit of lyrical analysis in class, and we could probably do more. I certainly don’t view the lyrics as secondary; I’m just more adept at discussing the tonal and rhythmic materials of a song because my background and training is in music. Students in my class who find themselves drawn to the lyrical aspect of the genre often engage in lyrical analysis as a large-scale final project.

Do you think metal lyrics are metaphorical to the political/social/economic/cultural (PSEC) factors you mentioned in the syllabus?

Yes and no. While metaphor and symbolism are certainly at home in the metal lyricist’s toolbox, so too are honesty and bluntness. One of the refreshing elements of certain metal lyricists is their ability to cut through the typical songwriting blather and get to the truth. Bands like Slayer may, at times, court controversy, but they speak what is on their mind in ways that U2 and Bob Dylan never could and never will.

If heavy metal has a message, or some contribution to the history of art, what do you suppose it is? Can it be handily summarized, or is it a messy categorization, like the list of attributes of Romantic poetry that ends up being more of a laundry list than a central topic statement or mandate?

Funny, I was just grading my students’ mid-term exam, which consisted of one question: “What is heavy metal?” They could choose to answer it any way they like. And the prevailing thought was that heavy metal is the disturbance of what is considered normal, polite, or acceptable, whether musically, visually, behaviorally, or in the direction of chaos and/or ecstasy. It’s hard to encapsulate in a single sentence. Although it is incredibly subjective, I think the message ends up looking like a collection of things, a nexus of truth, rebellion, perseverance, and power.

Your syllabus mentions having guest speakers and musicians. Anyone that the larger metal audience would recognize?

Here in Rochester, we are well-positioned in terms of connections to heavy metal. Metallica recorded Kill ‘Em All in downtown Rochester (at what is now known as Blackdog Studios), and I have taken students there on a pilgrimage of sorts, since the layout of the studio is basically the same as it was in 1983. We’ve got Manowar to the east of us and Dio hailing from a little further beyond that. In terms of actual guests, I have been very fortunate to get to know Danny Lilker (who lives in Rochester), and I have asked him to visit on multiple occasions. You should see the looks on the faces of the students when six- and-a-half feet of pure metal walk through the door! Danny is extremely generous and entertaining, and his visit is always a highlight of the class. Chris Arp (Arpmandude) of PsyOpus is also local, and he is incredibly intelligent and energetic in the classroom. He came and played for us a few weeks back and just blew everybody away. I have been in contact with other metal “celebrities,” but our schedules haven’t lined up well enough to facilitate a visit. I do host other speakers and musicians, either fellow professors or members of local bands, and I am very fortunate to have some extremely talented up-and-coming metal musicians enrolled in the class, most notably, Cody McConnell of Goemagot.

How much of the underground metal (death metal, black metal, grindcore) do you teach? Do you see it as a recognizable extension of earlier metal, or has it gone to an entirely new place?

I feel I must include the more extreme or underground subgenres of metal in order to tell the story effectively. Everything is connected musically in some way, even if just through the use of power chords or the tritone. Considered more broadly, any underground scene is normally the result of the continuous rebirth of metal that has defined the genre’s existence; indeed, it is this “diversification” that has given the genre its incredible staying power. Thrash bands wanted to push the boundaries established by the NWOBHM, early metalcore bands wanted to push the boundaries of thrash, and it goes on and on. It is a never-ending process of creative destruction and reinvention, so the newer and more extreme tangents of metal are just as central to the story as the classic material. Besides, if I skipped Grindcore, how would I find a way to include “You Suffer” by Napalm Death?

16 CommentsTags: academia, metal

Not for the first time I find myself reading a cringingly bad article from the Irish press about metal. This one is entitled Alt, Nu, Funk, Rap: there are many colours in the heavy metal rainbow and it ran in the Irish Times yesterday.

Not for the first time I find myself reading a cringingly bad article from the Irish press about metal. This one is entitled Alt, Nu, Funk, Rap: there are many colours in the heavy metal rainbow and it ran in the Irish Times yesterday.

Academia’s

Academia’s  Look, science journalism, it’s time for us to have a chat. I read you every day, but when you write about metal, I wince even before I read the article.

Look, science journalism, it’s time for us to have a chat. I read you every day, but when you write about metal, I wince even before I read the article. The pace of recognition for metal studies in academia accelerates with

The pace of recognition for metal studies in academia accelerates with